Self-Portraits

Navigating a local art scene as a young artist can be, to use one of Ashley Doggett’s favorite words, “harrowing.” The term means something like splitting open at the head. A harrow is a tool with lots of blades on it, designed to tear up the earth. It was harrowing when my mom had an operation that required drilling a hole in her skull. Could Nashville’s art scene be so wicked? “Honestly, I don’t get out much,” says Doggett. But you have to get to know Ashley Doggett, the Nashville-based, transfeminine, person of color artist with unlimited potential and unreal exposure for someone who has yet to graduate from art school.

I meet up with Doggett at Watkins, which currently serves as her school, workplace, and studio. “I’m a Nashville native. My twenty-first birthday was in August. I have experienced the changes in Nashville. I grew up in East Nashville,” she says. “My work was recently featured in AfroPunk, The New Engagement, Creamer, and Nashville Arts . . . People have told me I’m an old soul.” I can see that; there is a striking maturity to Doggett’s art. “I work on technique all the time . . . but the content has always been there.”

Let’s start with the self-portraits since 2014. War Stories (2014) is actually harrowing. The collages are cut-out headshots superimposed with various sculpted facial features: eyelids sewn shut; a bullet hole in the forehead; splitting, decomposed, missing, and bloody tissue around the face. One can imagine an early art school student compelled to explore her identity and coming up with an incomplete, distorted, violated self. But the compositions here are already far beyond what we might expect from a college sophomore.

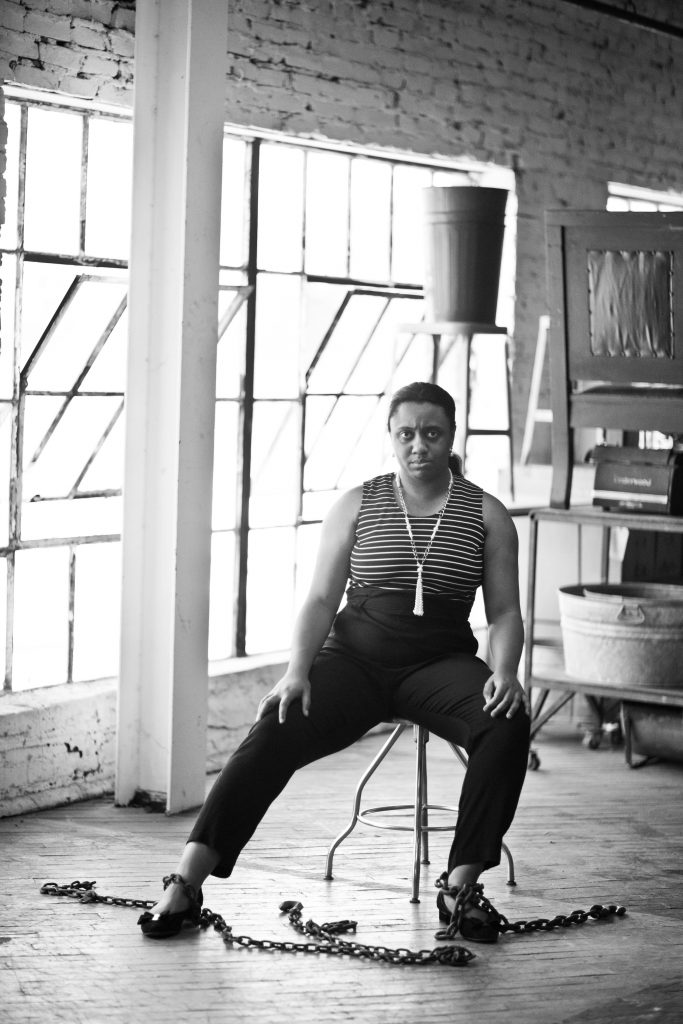

Work Is Entitled to All it Produces (2015) demonstrates Doggett’s progression as an artist. In this Sherman-esque series of photographs, she now positions the self in Victorian-era costume among period fabrics and props, as if the artist is quilted into a confining historical narrative that exists with or without them, a narrative that the artist can take agency within but cannot escape. Here one can imagine an art student inspired by the currents of contemporary visual art, but art school students are not supposed to make such coherent mixed media work—installation, performance, and photography—appear as natural and personal as Doggett does here. Her professor gave her a C for printing it on the wrong paper. There are conventions in art. “You don’t do that!” Doggett imitates the professor, and then resolves, unapologetically, as if speaking back, “Oh yeah? I just did.”

Finally, Neo-Olympia (2016)—photographs of Doggett lying on her side on a bed, à la Manet—positions the artist not as a contradicted or challenged self, but as one that is self-consciously willing to challenge art historical conventions, including its raced and gendered assumptions. It is a profound shift of consciousness in any field when a practitioner moves from exploring one’s self to interrogating the parameters of the world in which the self is embedded. Doggett’s art and self-concept reflects that shift. “Me and a friend did that on a whim . . . in an antique store . . . I just noticed the bed looked like that Manet painting.”

Translocal Pathways

“I have been told to tone it down,” Doggett tells me, referring ambiguously to local audiences, some peers, and some professors. Even her mother—whom she describes as a hero, a collaborator, and a critical voice not found at Watkins—has pushed her to work in a way that people can relate to, to make subject matter that is not so “in your face.” Still, while Doggett credits some of her mentors at Watkins as encouraging and even promoting the work to local audiences, she has found an audience at a global rather than local level.

Doggett’s exposure has come through online and print publications that have an international scope. AfroPunk is a critical culture and politics publication put out by a young, black arts collective based in New York City. Creamer is an online and print journal from London. The New Engagement is from California. Coming from the global centers of the art world, these are distinguished sources of publicity for anyone, but especially for someone who has yet to show in her own city. To be fair, she is now getting local press and local shows too, but, says Doggett, “I don’t feel committed to Nashville . . . Don’t get me wrong, I love Nashville, but people on the national level are encouraging, and Nashville is . . .” Understandable.

Let’s appreciate how rare it is to meet an artist that has been able to get such attention before paying her proverbial dues in a local scene. The image of the artist starving alone in the garret before being “discovered” is of course a romantic myth. Many artists develop networking skills in art school and/or by going out to as many art events as possible, around which certain conversations and opportunities begin to take shape. Many artists travel a lot, extending those networks and opportunities to other places. Some take an organizational role, launching galleries and project spaces that animate these translocal scenes. In the twenty-first century, artists are increasingly “placemakers” as well, advancing the supposed virtues of their local scene to tastemakers in other places who are increasingly interested in what goes on outside their own scene. But Doggett hardly gets out at all.

Although Nashville’s creative city mantra means attracting young artists, Doggett finds that the dominant artistic voice here is a white, male, cisgender one. It is not that alternative voices are not welcome, but until critical dialogue about race, gender, sexuality, and development politics are a central part of Nashville’s arts identity, Nashville won’t contain Ashley Doggett. Of course, moving to New York or Los Angeles would not solve this issue, but it seems easier to imagine Doggett connecting to global audiences from the global art centers.

Doggett spends sixty hours per week at Watkins and another ten hours a day working in her home studio, which is in a closet. She has effectively utilized the Internet, promoting her work on social media platforms such as Tumblr and Instagram. But before we assume that the Internet allows artists like Doggett to “live anywhere,” we should note that it has become just another career prerequisite that can be as homogenizing as it is distinguishing. Most artists have online profiles, and most artists still do the monthly art crawl ritual. But not Doggett: “I’ve only been [in] one art crawl, and I’m only going to the next one [which took place at Zeitgeist last month and featured four of Doggett’s pieces] because my mom wants to see the show.”

A History

I ask Doggett if we can do a studio visit. She shows me what was published in AfroPunk: two cross stitchings on fine lace; one of a mammy head with the caption “MAMMY IS DEAD,” and another head of an ambiguously gendered, dead-looking character with the caption “THROWN OVER BOARD.” These are part of a series Doggett is working on called A History, a mix of drawings, paintings, and cross-stitchings shown at the Zeitgeist gallery in September.

Based on plantation romance novels, the A History images are disturbing, depicting sexual violence, masked and distorted faces, white masculine domination, and contradicted black femininity. In the drawing titled Master Leeroy’s Mansion, Master Leeroy is blinded by the confederate flag, and his penis is hanging out of his pants while a slave woman in chains appears to be trying to seduce him. In the painting titled A Scourge of Antiblackness and Self Hate, Courtesy of Master Leeroy, a black woman is posing for a portrait in whiteface while being haunted by a silent crowd in blackface.

There is a brilliant, albeit painful, lack of affirmation in A History. Plantation romance novels—widely read in the South and elsewhere from the late antebellum era up to Gone With the Wind (1936)—misrepresented social life in the South in ways that sought to rationalize slavery and justify Jim Crow. They invariably featured genteel Southern men, idolized Southern belles, and contented slaves happy to protect their owners from harm. Doggett’s work turns those narratives on their head, closer to where they belong, but the result is frustrating. In A History we see double negations, masks facing off against masks, representations of representations, and fragmented characters.

What I learned from Doggett is that it is the frustrations that ring true. Harrowing is working backward against a hegemonic narrative in which the truths are more disorienting than the lies.

Suggested Content

Chelsea Kaiah James

Why aren't there any ears sculpted onto the presidents of Mt. Rushmore? Because American doesn't know how to listen. - Unkown

Contributor Spotlight: Dylan Reyes

When I create, I often think of what Johannes Itten said, “He who wishes to become a master of color must see, feel, and experience each individual color in its endless combinations with all other colors.”. I’m also inspired frequently by love and loneliness and want folks consuming my work to be encouraged to start paying attention to the little details in everyday life, appreciate the simple things, and let them eventually inspire you! Ultimately, I’m just trying to become a mother fuckin master of color.

Secondhand Sorcery

A look inside the beautifully cheesy world of Crappy Magic