REVAMPING CULTURAL TOUCHSTONES IS A TRICKY THING. At best, it enriches art that’s already crucial to millions of people’s lives. At worst, it messes with something that was perfectly fine in the first place. Nobody wants to see Anakin Skywalker superimposed into Return of the Jedi, nobody wants Queen without Freddie Mercury. In Southern parlance: if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

That’s why the thought of Peter Frampton re-recording some of his most beloved work, including tracks from Frampton Comes Alive!, is potentially cause for concern. The eight-times platinum, decade-defining live album—the album that was, as Wayne Campbell joked, “issued” throughout the suburbs and mailed with samples of Tide— doesn’t exactly beg for revision. For fans that grew up with the record, the thought of a talk-box-less, acoustic version of “Do You Feel Like We Do” might seem downright blasphemous.

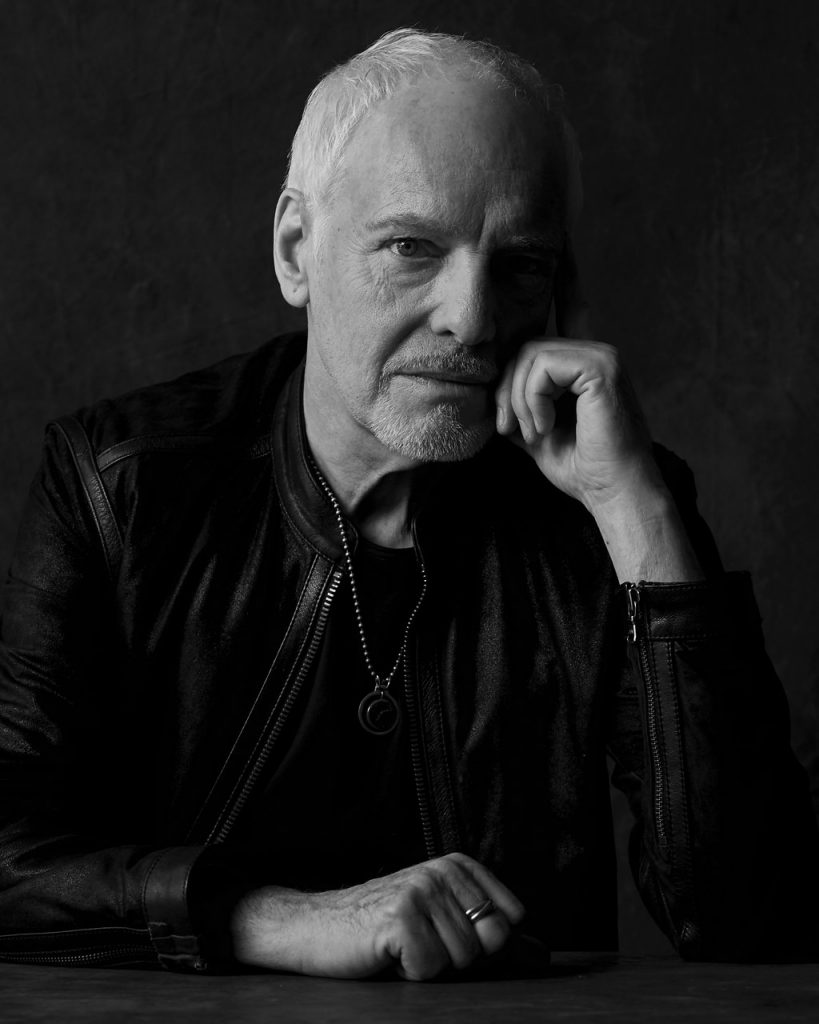

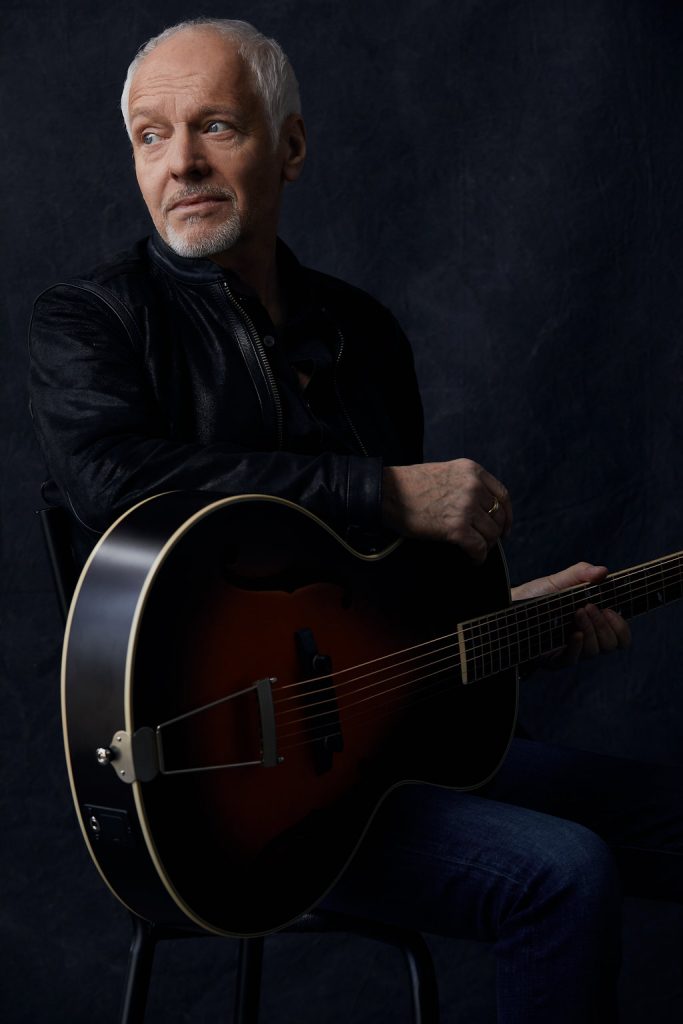

But that’s exactly what Frampton did on last year’s Acoustic Classics. The album reimagines the rock icon’s staples as sparse, jazz-tinged standards that wouldn’t sound out of place in a living room or on a front porch (think recording a demo with your buddies over a long weekend). And the album’s intimate feeling carries over to Raw: An Acoustic Tour, which will make its way to the Schermerhorn Symphony Center later this month. There’s no triple-pickup black Les Paul, no white bell-bottoms, and no talk box stage banter. Just Frampton and Music Row mainstay Gordon Kennedy—who’s penned hits for Eric Clapton, Ricky Skaggs, and Garth Brooks—swapping solos and singing honest songs.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that Frampton tapped Kennedy to be his right-hand man on the tour, considering the English expat has lived in Nashville for the past six years. However, it’s hardly Frampton’s first stint in the city: he lived here for about half of the ’90s, and he’s made countless trips to record with friends like Kennedy and Vince Gill, who recently took Frampton to his first Preds game (Gill sang backing vocals with the house band during intermission, which really blew Frampton’s mind: “Where else in the world at a hockey game do you see Vince Gill get up and take the back seat?”).

It’s indicative of what Frampton loves most about Nashville, a city that he’s proud to call his home. “The community here is so great and supportive. People really do come to other people’s [aid] here… Certain places you just feel more comfortable than other places, and this has the big C for comfort.” He tells me about his time here, his admiration of Django Reinhardt, and yes, the talk box, via phone from his Music Row condo on a weirdly warm February morning.

You finally made the full-time move to Nashville in 2011. . . As someone who has been involved in the Nashville community—you even played Mayor Barry’s first State of Metro address, the subject of which was growth with intention—what do you think about Nashville’s seemingly never-ending growth and national exposure?

I’m not going to say we build a wall [laughs]. I would prefer that it doesn’t get too big too quick. . . I love Atlanta, but you saw what happened there. People say we don’t want it to turn into Nashlanta. There’s nothing you can do about it… It’s no longer a secret, not that it has been, anyway. It just seems Nashville’s time for people to gravitate toward here. I’ll do whatever I can to help. . . I’ve spoken with Megan, Mayor Barry, on quite a few different occasions. We’ve emailed and everything, about Nashville and the country in general. I applaud her. She’s wonderful. She’s done so much already. [It’s] a continuation of the last mayor, who was also great. Nashville’s very lucky to have her, I think.

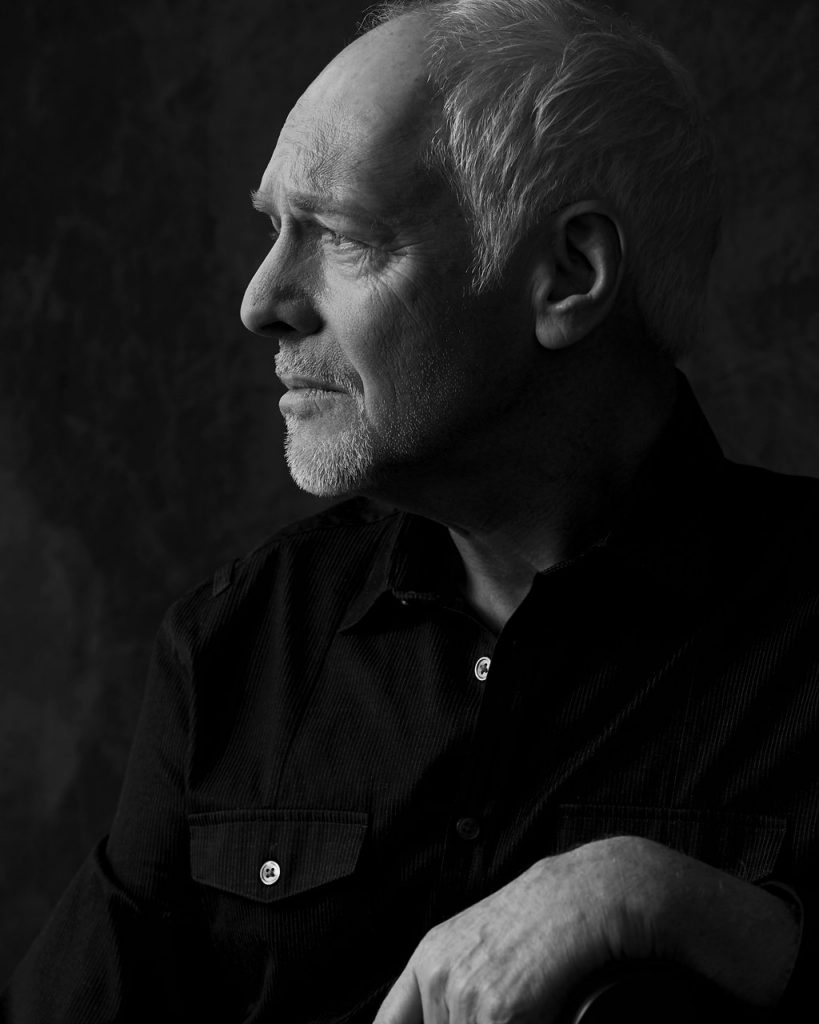

I think that a lot of our readers might not be aware that you’re an avid Django Reinhardt fan. That makes sense, because I can hear hints of Django, or even somebody like Al Di Meola, in your playing on Acoustic Classics. Was Django on your mind as you were recording and reworking these new songs?

Django’s always been on my mind. He’s always with me. I think I have every recording he’s ever made, but then every now and again, someone sends me something [and says], “Have you got this?” I’m close. It started when my father brought our first record player, the one where you lift the top and you lift the arm up, and you put the arms on it. It’ll play like ten albums, with a volume control that is the On/Off and one sound control. It was a Dansette in England, I don’t know what the equivalent is [in the United States]. Everybody got those when they came out.

Anyway, my Dad brought home our first record player. For Christmas, I got The Shadows’ first album. Hank Marvin was the lead guitarist of The Shadows, he’s a dear friend now. They were like the instrumental Beatles, just before The Beatles, like ’59 or ’60, something like that. So I was just gung ho, I learned every lick. I can still play it, all the early Shadows tunes. Then when I would take that album off, my Dad would reach for the other album that we had—we had two [laughs]. It was what my mother and he, their kind of music, that they danced to during the war, pre-war, after the war, whatever. It was Hot Club de France, which was Django Reinhardt, Stéphane Grappelli, Django’s brother [Joseph Reinhardt], a bass player, and a drummer.

He put this music on, and I couldn’t get out of the room quick enough. This was old, fuddy-duddy jazz. I’m into rock guitar now. I’m eight years old, nine years old. Each time this would happen, it would play over and over again. I’d take the album off. After about a couple of times, I decided I would stay in the room and listen. That’s when it clicked. I went, “Holy crap. This guy is incredible.”

More than anything else, Django has been the [soundtrack] to my life. I go through phases where I reopen the thesis [laughs], and I go back in with today’s technology. I’ll take a solo, or I’ll take a melody part that is just unbelievable and beautiful and fantastically played. I will just put it into this thing called Amazing Slow Downer—that’s what it’s called. I’ll slow him down, just like I used to in the old days, slow down the albums. The thirty-three and a third you could put on sixteen, and that would be an octave lower, but slower. There was method to our madness back then too. But that’s it. Yes, Django has always been an incredible inspiration to me. Inspiration—I chose someone that I will never be as good as, because I don’t think there’s very many people on this earth that have been or maybe will be.

That makes sense that he had always been with you, though, because when I first heard Acoustic Classics, I thought it was interesting because Humble Pie, obviously, had acoustic songs on Town and Country [1969], and you did an acoustic set on the accompanying tour when no one else was really doing acoustic stuff. I wanted to know: Do you feel like you’re coming full circle in this odd way since you’re now on another acoustic tour?

It’s just part of what I do, and I never incorporated it into the live playing before. Like as you said, with Humble Pie we started off coming out and doing two or three acoustic numbers when we first came to America. But it’s something that I’ve always done [on my own]. I write mainly on acoustic, sometimes on electric, sometimes on a keyboard. . . When I made Acoustic Classics it was just an idea to, rather than redo all my songs that people really knew well the same way—I never want to repeat myself that way—[I’d instead] go back and take those songs and reverse engineer them back to when I’d just written them. Where forty years later on stage, they’ve taken on a whole different life of their own.

"WHAT I’VE GOT IN MY HAND IS ALL I’VE GOT TO MAKE IT WORK: ONE GUITAR."

When I went into the studio to cut songs that I’d played over and over again with the band, I started with one acoustic [guitar] and came into the control room, thought I’d done a great job. Then listened and went, “No, this isn’t what I want.” [It sounded] like me with the faders of the band down. It [wasn’t] the intimate, just-finished-the-song performance that even I would get myself when I would be playing it for the first time in its entirety. So I wanted to go back and try again and make it much more intimate, as if you had come round, we’re having coffee, and I said, “Oh, I’d really like to play you a song I wrote last night.” Hopefully you’d say yes [to hearing it], and I could play it to you [laughs]. I would be a little nervous, I would be very passionately involved with the song, as it was just written. It would be a completely different performance of say, “Show Me the Way,” or “Lines on My Face,” or “All I Want to Be,” than you would see me do live with the band. That’s what I wanted. I feel I achieved that.

I read somewhere that you called it “playing without a net.” It’s a very naked thing. Were you nervous that maybe people wouldn’t like the way that you reworked these iconic songs that they had all these memories to?

Well yes, actually. That’s another reason I didn’t want to do it for so long, I think, was I just didn’t know whether people would want to hear it this way. So yes, I was nervous. I was nervous until I was on stage for thirty or forty seconds. Then I looked up, and everyone was sitting forward with a big smile on their face. I went, “Oh, I think I’ve done the right thing.” Again, when I meet the people afterward that have chosen to come back, whatever, I ask, “What did you think?” They say, “We’re not sure which one we like better.” They’re 180 degrees different, the electric show with the band and the acoustic show, obviously. They said, “You’ve got to see both.” That’s what I feel. I’ve found another outlet live for what I do that I really enjoy, but it’s completely different. There is no net, you’re right. There’s no feedback from my Les Paul and my ten thousand watts of Marshall amplifiers. What I’ve got in my hand is all I’ve got to make it work: one guitar. Obviously I have Gordon Kennedy, my dear writing partner for seventeen years. . . He comes out and joins me so we can both play some lead guitar and have a rhythm playing. That’s as big as the band gets.

I did notice, though, that even on the Acoustic Classics version of “Show Me the Way,” you include the talk box.

I know [sighs].

It’s an effect that’s obviously become synonymous with your name. Do you ever get tired of the association?

I don’t get tired of the association. . . The reason it was so successful for me is that I only use it on a couple of songs. A little bit goes a long way for me [laughs]. It’s such a powerful effect for $150, which I didn’t pay. I got given one in the beginning. 150 bucks, I think it was. That’s a pretty cheap gadget that changed my career by now being associated with this. Along with Joe Walsh, who is a dear friend, and was the first guy to have what I call the iconic solo on “Rocky Mountain Way,” that talk-box solo—it was fantastic. He’s tremendous. We’ve spoken as the guardians of the talk box.

What advice would you give to young songwriters—particularly the swaths of young songwriters living in Nashville— looking to write the next “Baby, I Love Your Way,” or some huge hit like that?

Well, the thing is that I have never been able to sit down and say, “Today I’m going to write a hit song.” They turn out that way or they don’t [laughs]. . . There are format songs that can be written that way. There are specific writers that don’t seem to have a problem with repeating themselves, and it’s the same three chords and it’s that high melody for the chorus. That’s the last thing I’m interested in. It’s something that moves me first—I’m not writing it for anybody other than me. Every time I sit down to play, it’s a totally selfish thing. If I like it, and I come up with a new idea, then I’m going to finish it.

You’d be amazed at the amount of stuff I throw away. I mean, I sit down with my iPhone or my digital recorder— I’ve got one in every room. I pick up a guitar or sit down at the piano, and I record everything I play. Then at the end of the day I throw away 99 percent of it, and maybe have one little riff [where I say], “Oh, that’ll be something.” You just can’t stop it, stop writing, because it’s not like riding a bicycle . . . I need to constantly keep pushing myself to find something different. [While writing, I’ll say], “I’ve done that. I did that. No, not that chord with that chord, no. Oh, I’ve never done that chord. Wow. You get a little goosebumps on that.” Then you go, “This is one I’m going to finish right now.” That’s what I’m looking for all the time: the one that gives me goosebumps.

Acoustic Classics is available now, and Raw: An Acoustic Tour is coming to the Schermerhorn Symphony Center March 26.