After Party

The heart of North Nashville, on the first Saturday in April 2016, is a venue its proprietor calls Art History Class Lifestyle Lounge and Gallery. It is all that and more, but I think of it as Thaxton’s Place. There is no sign. Outside, the building appears unoccupied. Other than the stencils on the boarded-up building next door (“That’s my signal,” Thaxton says), only an address decal marks the right place, where people are gathering after the downtown First Saturday Art Crawl for an event Thaxton calls the Whiskey and Wine Social. It’s not a secret or exclusive club (Thaxton welcomed me to invite anyone), but it might be the coolest spot in Nashville, so I’ll leave out the address.

Inside, the room is endlessly inviting. It is an Art Gallery, at least: the room is open; new artists are showing; scarves from Africa are carefully arranged on a shelf; one wall is painted rococo wallpaper. It is a Lifestyle Lounge: antique chairs line the walls; a chess set is in use; Tribe Called Quest is on the deck; a piano is adorned with stacks of records, books, and music magazines; the space invites culture and conversation. It is also Art History Class, but not the one you took in college: the room is a portal to African American cultural history and Black Nashville history, which are widely overlapping categories and converge here in the present tense on the north side of town.

At 11 p.m. the room is already packed. There are artists, young and old, professors, graduate students, chess players, and artists’ moms. Thaxton is shaking hands and bumping shoulders with arriving guests while prepping the space. He holds a dust brush in one hand, runs bags of ice in the other, fixes a speaker cable with his foot, and still manages to acknowledge everyone in the room. I watch the room fill up as I sip on wine, bob my head, look at art, and make small talk. Like any art gathering, the crowd organizes into a handful of migrating conversation circles. The maitre d’ chats me up on environmental issues. A proud mother wants to make sure I know that I am looking at her daughter’s art on the wall.

As a sociologist, I’ve followed artists in Nashville and other cities for years while doing dissertation research, but North Nashville artists always eluded my “snowball” sample. I have written on the topic of art crawls, and I’ve written that art crawls can become racially exclusive (white), which in turn can spur gentrification (by design or not) because, in academic parlance: art legitimates the appropriation of space.

Now I am the only white guy in the room, welcomed and privileged to write about this Afrocentric space. The last thing I want to do is hype an art scene and a neighborhood where gentrification pressures are very real. I issued this dilemma to Thaxton several days earlier, but he was already well aware: “If the neighborhood does change, wouldn’t it be better that this place is here?” I agreed. When I asked how he wanted to be represented in this profile, he insisted, “Emphasize the neighborhood. It’s all about North Nashville.”

“You not gonna stay ‘til 3 a.m.?” Thaxton teases me on my way out, before promising that, like the Harlem salons of the 1920s, this all-night soiree has only just begun. The vibe will only get more expressive. The scene can only become more cohesive. The venue will only become more definitive of its time and place. He is thinking well ahead of the party at hand.

Thaxton Abshalom Waters

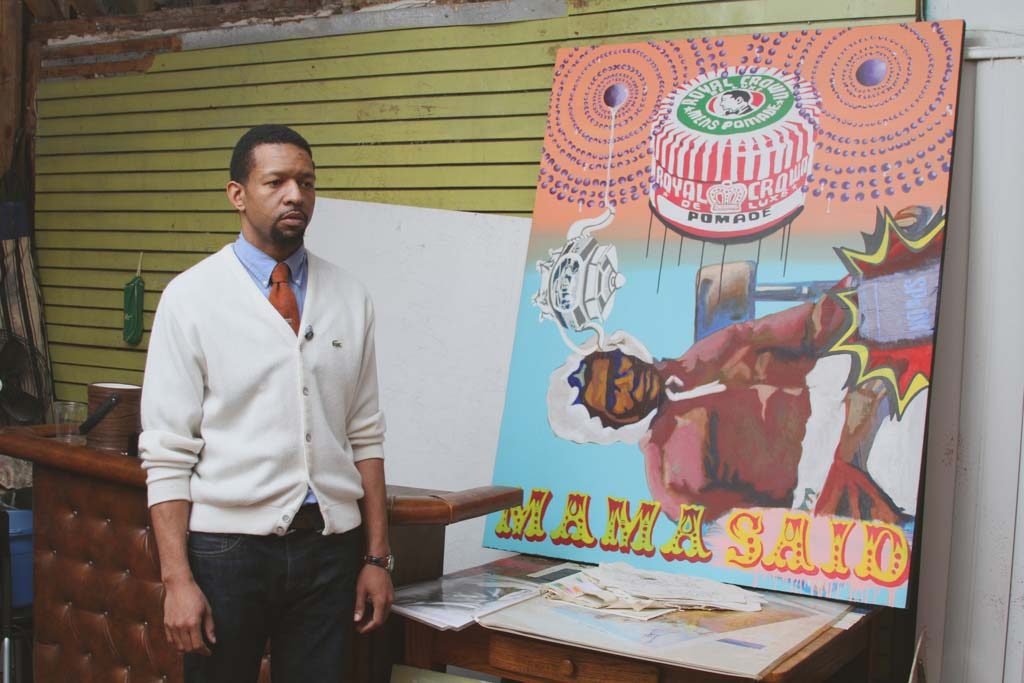

Thaxton used to carry his paintings under his arms along Jefferson Street, between his home studio and the Showtime Barbershop, Na’sah’s Nail-Tique, and anywhere else he might find an audience. Inspired by Panther illustrator Emory Douglas, Thaxton carried paintings of Black Power and black culture—$100 for a Malcolm X, $120 for “Live Jazz.” He painted what sold. If someone wanted Dexter Gordon, Thaxton could paint him. If someone wanted Stevie Wonder, Thaxton would. He painted a lot, out of necessity.

“I was trying to feed my family,” Thaxton says. He squeaked by, but being a starving artist works better when the artist is single, the poverty is voluntary, and the economy is good. “I always knew how to make art. My dad was an artist. But at that point I didn’t think deeply about it.” For Thaxton, his art was a hustle, a means to survive after the recession wrecked his first entrepreneurial effort, a T-shirt and knickknack store called Hebroots.

His art career took a turn after a chance encounter with longtime Nashville artist and Tennessee State University professor Michael McBride. The way Thaxton tells it: McBride approached him while he was painting a mural on Monroe, told him he needed to step up his art game, and encouraged him to spend some time at the TSU art department. At TSU, Thaxton networked with McBride and Samuel Dunson. They taught him to think beyond sales, to think about concept, to get personal in his work. He learned to interrogate an ashtray, a hair product, the wallpaper; he dug into his childhood; he read about Harlem and North Nashville. He made collages that tapped the roots of his memory. He got shows in academic galleries. He became an artist in an art community, and the community became his art. He still paints too. Thaxton has since found employment as the art gallery coordinator at the Nashville Public Library.

“I went from selling paintings to the people in the neighborhood to telling the story about the neighborhood!” Thaxton says emphatically, as if his path to self-discovery was the same North Nashville sidewalk he takes every day. Fair enough, but it seems to me that North Nashville is not simply Thaxton’s inspiration and source material. He makes the neighborhood. In addition to the Whiskey and Wine Social, Thaxton uses his venue to host spoken word events, group drawing/painting workshops, a Wu-Tang–inspired kung fu movie theater, and a community discussion/lifestyle forum he calls Shop Talk. Thaxton’s Place is like an installation of an art gallery in an art gallery that has curated a community in North Nashville.

North Nashville

It was way back in 2010 that Thaxton went from being from North to being North—ancient history in Nashville perhaps. The city has since learned to embrace its artists and its neighborhoods. The New York Times has come and gone. ABC is poised to stay. Property values have doubled. We’ve become a “creative city.” History ended when the millennials moved in.

But the North Side unfolds on a different trajectory. North exists despite the Opry, cowboy boots, professional sports, valet restaurants, condo towers, or other It City icons, past and present. In the middle decades of the 20th century, North was shaped, literally, by the red line—Federal Housing Administration code for whole neighborhoods deemed “too risky” to invest in because of the presence of black residents (i.e., no mortgage loans, no wealth accumulation). It was shaped again, razed and bisected actually, by the construction of Interstate 40. In the 21st century, the effects of white flight continue to determine its meaning. The New York Times did not go there. Nashville does not go there. North property values remain significantly lower than other parts of the city, not because of its near downtown proximity.

Yet, among the many artistically, culturally, and historically relevant quadrants in Nashville, North might be the most relevant. In fact, you would have to go to New York City to find a collection more representative of the origins of an American Art World than the Stieglitz collection at Fisk University. Thaxton could talk for days about the artists and characters that have made this neighborhood what it is. Aaron Douglas, the Harlem Renaissance painter who made art for The Crisis and illustrated book covers for Richard Wright and Zora Neale Hurston, moved to North Nashville during the Great Depression to become the first chair of the Fisk art department. David Driskell was the second. Fisk is also responsible for bringing Harlem poets and writers Arna Bontemps and James Weldon Johnson, and for giving a platform to the generations of John Wesley Works and the Fisk Jubilee Singers, who were curating and circulating original music around the world long before Nashville’s Music City moniker stuck. W. E. B. Du Bois, who wrote about “the problem of the 20th century . . .” lived in North Nashville and studied at Fisk. Nashville natives and early civil rights activists James Napier and Preston Taylor were key subjects in Booker T. Washington’s Character Building. During the early 1960s, North Nashville was home and refuge for nonviolent protest organizers Diane Nash and James Lawson, while Little Richard and Jimi Hendrix rocked out in its bars. North has local folk heroes, too, like Jefferson Street Joe (Gilliam), the ’70s Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback who could throw the football from one TSU end zone to the other (but who, despite outplaying Terry Bradshaw during the 1974 season, did not play in Super Bowl IX).

Where does Thaxton fit into all of this? He might say he is just another artist in a long history of artists in North Nashville. But he is also the one telling its story, and it turns out that he was born here, wrought by the neighborhood that he now creates. “I don’t want this [Art History Class Lifestyle Lounge and Gallery] to be a museum of what was, but of what [North] is, and what it could be,” says Thaxton.

Sociologists often describe places as having a distinct “character.” Neighborhoods like North Nashville accumulate experiences, resist or adapt to change, and “act” in both scripted and improvised ways. North has and will always confront external pressures. Now Germantown keeps getting bigger; tall skinnies are going up; hipsters are spotted on Buchanan. But places are also fashioned by the images and memories that their denizens embody and curate. What I learned from Thaxton is that art is a place, but North Nashville is not just another place. Thaxton’s art is locating origin stories in an inclusive black space in a city that once turned its back and now wants a piece.

Suggested Content

Chelsea Kaiah James

Why aren't there any ears sculpted onto the presidents of Mt. Rushmore? Because American doesn't know how to listen. - Unkown

Contributor Spotlight: Dylan Reyes

When I create, I often think of what Johannes Itten said, “He who wishes to become a master of color must see, feel, and experience each individual color in its endless combinations with all other colors.”. I’m also inspired frequently by love and loneliness and want folks consuming my work to be encouraged to start paying attention to the little details in everyday life, appreciate the simple things, and let them eventually inspire you! Ultimately, I’m just trying to become a mother fuckin master of color.

Secondhand Sorcery

A look inside the beautifully cheesy world of Crappy Magic