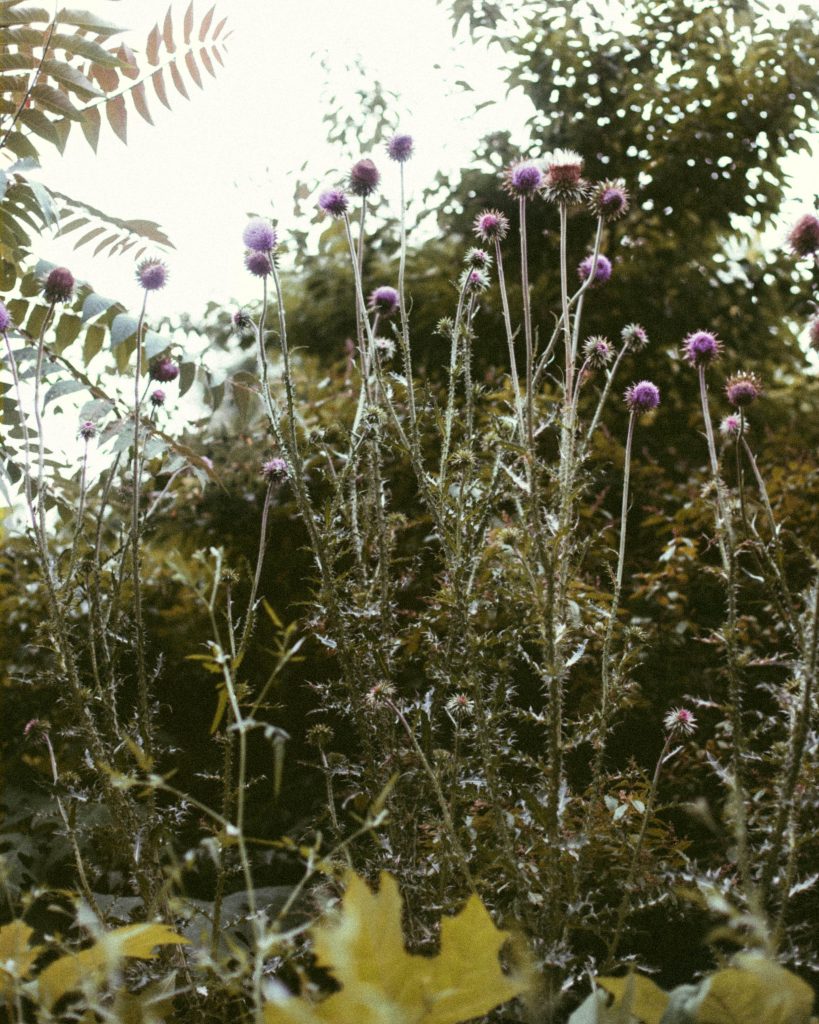

THE HUMBLE CLOVER, our sweet-smelling, lucky friend, has white flowers that you can grind into flour. Wild grapes store potable water in their wandering vines. Ragweed triggers allergies, yes, but it’s also a source of oil and a rich yellow dye. Cleavers are a sticky mess that, when gathered, hold weight and bounce back, making for excellent mattress stuffing. Even ground ivy can be dried and made into tea. Redbud. Garlic mustard. Poor man’s pepper. Sweetgum. All these, and more, we’ve seen in just the first few minutes of our walk through Shelby Bottoms.

Alan Powell, Nashville’s master forager and founder of Nashville Grown, is leading our group through the practical uses of practically everything we see around us. Here is dogbane, deadly toxic if ingested, but also a fiber second only to hemp in tensile strength. We can’t walk even a few feet without Alan pointing out another plant that’s edible, or medicinal, or both. I’ve walked this path from the nature center to the observation platform a hundred times, following the slow bend of the Cumberland, listening to the songbirds, and it’s as if I’m seeing it for the first time.

“It’s an ancient skill. A birthright. But it can easily disappear,” Alan says of his ability, placing himself in a long, unbroken chain going back to the very origins of humanity. The handful of guests along for the guided walk are devouring the wisdom he shares. Some are taking pictures with their phones, using apps that help identify plants. Others madly scribble notes, sketching a leaf, a vine, a branch, a hairy follicle. Alan is constantly asking the group to try and name the plants before he identifies them himself, and though I guess constantly, I am also wrong nearly every time. I am now certain that, were I forced to fend for myself in the wilds of Shelby Park, I would be dead before the parking lot was out of sight. The other floraphiles are correct much more often, even adding uses that Alan might not have considered. A delightful woman named Kathy bubbles with glee and excitement over the tea she’s started brewing from wild plants in her backyard.

Some time after our nature walk in Shelby, I meet Alan at Good Food for Good People in West Nashville. Painted across the side of the building is the slogan, “Love the People, Love the Planet, Love the Possibilities.” I hop in his car for a trip to a roadside patch of elderflower that he plans to harvest and sell to local restaurateurs through Nashville Grown, an organization he founded to connect farmers and food producers with chefs and other wholesale food consumers like schools and grocery stores. A list online lays out the available produce, with information about the farms and farmers, none of them more than one hundred miles from town. Nashville Grown tackles distribution and also provides a land-matching program to help settle farms in the area. By connecting local production and local consumption, the group helps break the cycle in which the majority of our food comes from thousands of miles away.

The front seat of Alan’s car is full of sticks and rope. “Primitive stuff,” he calls it, as we head out for the gleaning. I ask how he came to know nature so deeply, and he tells me his love of the woods goes back to his early childhood in Maryland. “Baltimore’s my official hometown, Nashville feels like my hometown,” he explains. When Alan moved to Tennessee in the seventh grade, his new home of Bellevue was the outer edge of the city. “Most of my spare time was spent with my friends, running around in the farmers’ fields, and the rivers, and in the woods.” Alan’s enthusiasm for the wild world grew along with him, and he filled his leisure time as an adult with walks to discover new flowers. “At that point it was really about aesthetics and little more,” he tells me.

His love for beauty also stretched into the acoustic realm. Alan always thought he’d end up as a professional musician and that his love of the natural world would be a passion and a hobby, not a full-time job. He has a degree from Berklee College of Music, and through both his solo career and with his band, Liquid Village, he explored all manner of sound and color: “I’ve played every style of music pretty much imaginable, and [I’m] pretty proficient at most of ‘em.” It was a Liquid Village bandmate that first introduced him to food from a CSA, or community-supported agriculture. The band’s bass player would hand out leftovers each week after practice, and for Alan, it was a revelation. “It was the best food I’d ever eaten,” he remembers. He began volunteer

ing at the CSA, eventually coming to run the whole enterprise for Jeff Poppen, the socalled “Barefoot Farmer” of Tennessee.

At the same time, Alan’s sojourns into the parks to look at flowers exploded when he attended a course on Native American philosophy. The class changed everything. “That really opened [me] up to a whole different world, of how nature and the physical world and the human person connect. Suddenly I was really interested in looking at plants through different eyes. Not simply, is this a beautiful plant? Is this a beautiful flower? Do I know its name? But now it’s, what else does this plant do in the world for people? Does it feed people? Does it medicate people? Does it create rope?” Reaching down into the pile of sticks, he pulls out a piece of handmade rope, wound from natural fibers.

In the years since getting involved with the CSA, Alan has established deep personal relationships with farmers throughout the region, and those friendships are at the heart of Nashville Grown. Only recently has he started integrating his two worlds—the farm supply chain and wild foods—but since he began offering foraged fare through the site, local chefs can’t get enough. I ask him how he convinced those first few chefs to trust his wild food expertise, that he wasn’t going to poison an entire restaurant full of people, and Alan answers with a smile. “If I go in there and I eat something in front of someone and I say, ‘You should try this!’ Then the fact that I put it in my mouth first alleviates a little bit of any potential anxiety they may have been harboring . . . but it was a slow process of building trust and faith in one another.”

Many chefs will put in special orders for hyper-seasonal ingredients. The elderflower we’re harvesting today isn’t ordered yet, but Alan is confident that it will move quickly, for use in cocktails and simple syrups at places like Rolf & Daughters and The Wild Cow. We pull up next to an empty lot in Cool Springs, though the “For Lease” sign means this elder grove may not be around next time Alan comes to check on it. We step around the trees—“Watch out for snakes”—and position ourselves so that we’re able to reach the higher branches, trimming the wide fans of blossoms. Light yellow pollen sprays into the air, and we’re surrounded by a floral, sweet perfume. Quickly, we’ve filled a large plastic bin with flowers and we’re on our way.

We take a detour to try and gather some rare black raspberries. The stop is a bust; either it’s not the right day or birds found the patch for breakfast. “This is my life,” he explains. “I go back to places for mushrooms, and some years they show back up at the same place and some years they don’t. And you’re just walkin’ around in the woods. Fortunately, I find that to be a valuable endeavor all by itself.”

Being on the road with Alan is never dull. He’s constantly scanning the hillside, looking for seasonal markers that he’ll cross-reference with his mental map of the city and its environs. He points out a rocky outcrop lined with prickly pear cacti. We stop to taste wild bergamot in bloom. Cedars lining the roads are potential spots for gathering juniper berries. I find myself wishing I could see the woods around us as Alan does. In his eyes, every leaf has a purpose, each flower and shrub. His expertise has taken years of focused learning, and I’m just glad to be along for the ride.

Suggested Content

Chelsea Kaiah James

Why aren't there any ears sculpted onto the presidents of Mt. Rushmore? Because American doesn't know how to listen. - Unkown