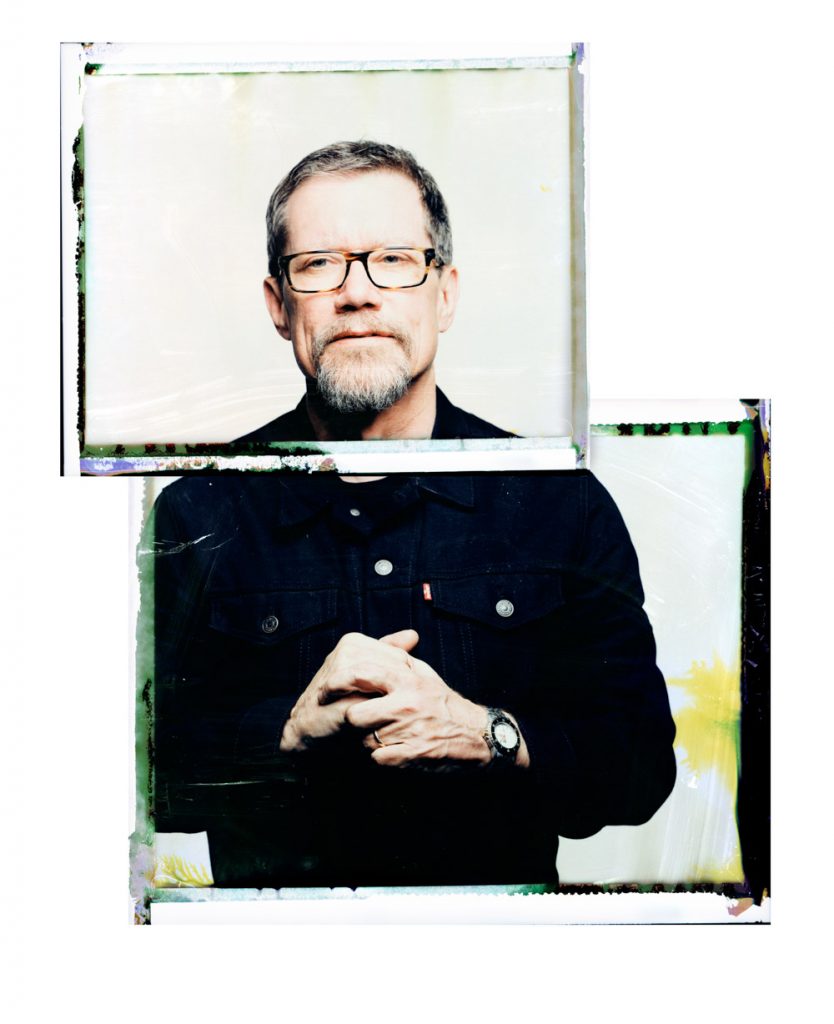

“I didn’t really have a plan for my photography, and I didn’t know that it interested anyone but me,” Don VanCleave tells me from his deck, looking out into the expansive South Nashville woods that are his backyard.

As he shows me around, he speaks of “heroes” like William Eggleston, Danny Clinch, and Jim Marshall with reverence; I see books of photography and assorted photography gear littered around; and there are prints—some his own, some his aforementioned heroes’—on practically every available wall space. I finally ask why, after almost forty-five years of shooting, he’s just now showing his photos to the public.

“It wasn’t [a] big attempt to hide what I was do- ing. It’s just I was busy having a career, and this was my hobby.”

Busy is an understatement.

After growing up in Macon, Georgia, watching legends like the Allman Brothers perform, Van- Cleave went on to open Magic Platter CD in Birmingham with his wife in 1988. In its fourteen years, the store achieved legendary status itself, winning the National Association of Recording Merchandisers’ Small Retailer of the Year award twice and bringing acts like The Smashing Pumpkins and No Doubt to Birmingham for in-store signings.

During this time, VanCleave, along with a group of other indie record store owners, started the Coalition of Independent Music Stores. Founded in 1995, CIMS worked—and still works—with labels across the country to get indie stores the same buying power and promotional/marketing opportunities as industry mass merchants (like Best Buy and Walmart). VanCleave served as president until 2008, just a year after he cofounded Record Store Day.

He’d go on to become the COO of L.A. management company The Artists Organization, where he worked with acts like Lenny Kravitz and Soundgarden (among many, many others) for six years. To- day, VanCleave splits his time between managing Moon Taxi and working with local YouTube channel Made in Network.

Through it all, he’s had a camera (or two) around his neck. And now—thanks in part to a little push from Moon Taxi and local artist Herb Williams—his personal photos are on display for the first time ever as Southernacana, now showing at The Rymer Gallery through December 31.

INTERVIEW:

Explain the term Southernacana.

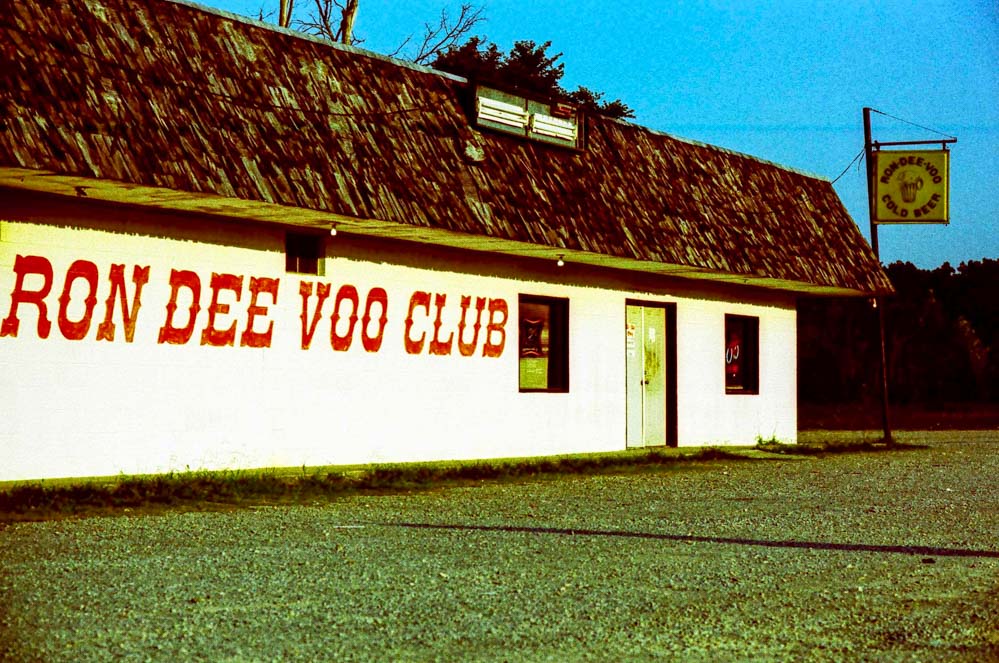

Southernacana is just a word I made up that kind of describes a little bit about what I’m passion- ate about. One of my big hobbies is to jump in the car, super before sunrise sometimes, and just head out into rural South. Just see what’s out there and shoot pictures of things that I find interest- ing. Sometimes I come back and have shot two frames, and sometimes I’ve shot six rolls of film and some digital too. I’m mainly a film guy. That’s what it’s about. Just capturing my eye on the deep South. Everything from music and culture to just side of the road crap that we drive by all the time that’s decaying and has a certain patina and look to it that’s very familiar to all of us, but it’s junk, basically. It’s just what I see when I ride around the South.

I’ll shoot things like dilapidated houses, rusting cars, any license plate with a Confederate flag on it, any Confederate flag I see—just got banks of that. In my show, I’ve got an entire hall of shots I took of the Ku Klux Klan in Selma in 1979.

Then I’ve got musicians from the South that I’ve shot. Cracks in a red clay road—that’s been a really popular shot over the weekend, just a giant picture of a baked red clay road. Deer heads on a wall at a restaurant, which I thought was the weirdest thing I’ve ever seen . . . An image of Dolly Parton’s mannequin. That’s the South—that’s what it really is to me.

You’ve really seen it all, growing up in what was arguably the most formidable, crazy time in Southern history.

Well I was . . . Golly, I can’t remember which grade it was. It might have been third. [It] was the year the schools integrated, and then I was of the first wave of integrated middle and high school. Our graduating class of ’76 was one of the first groups of kids that had gone through integrated education. So, I got to see it from a lot of different angles that my parents didn’t get to see the South from. And then kids afterward had no appreciation for kind of what went on in there. That kind of really formed me . . . And at the same time all that was going on, there was this music explosion all over the place and all around me. Just be- cause we were from the deep South, we weren’t immune to pop culture and what was going on. All that kind of mixed together for me.

How do you show the aspects of the South that you love while also capturing the region’s violent history?

I kind of try to show [both] together. The Klan shots in particular, Herb [Williams] and I really debated whether they go up or not, because we didn’t want people to take them the wrong way. We’re certainly not endorsing or glorifying the Ku Klux Klan, right?

I was like twenty and I went to Selma where my parents had moved, and I heard that the Klan was downtown recruiting. Not a rally, but a recruitment. I’m like, “Oh, there’s going to be trouble. I’m going to take my camera down there and shoot pictures.” It wasn’t like I was an agitator or protestor. I just wanted to be a fly on the wall, because that’s what I was into at the time with my camera, just trying to be invisible. This gave me a chance.

I went down there and it was five or six dirtball rednecks on the corners, handing out a newspaper in their robes and talking to people. I asked if I could take a picture. [They said],

“Yeah, sure. I don’t care.” I think I said it was for a class project or something. And what got me the whole time I was shooting was when I really realized how many black people there were in downtown Selma—because it’s a majority black town—that were walking around on a Saturday afternoon shopping, totally ignoring these guys . . . In that, there’s hope, because that was fourteen years after Martin Luther King walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, right?

My point of the whole thing was—this was fourteen years after Bloody Sunday and all that—and these people didn’t fear anymore. Fourteen years before, these guys would’ve had everybody scattering. Here, it’s like they didn’t matter. Nobody cared. There was no interaction. There was no tension. It was a Saturday afternoon and there was some guy that was handing out leaflets, and everybody was ignoring him except for some other rural white people coming in. It was very unimpressive as a situation.

That really struck me. I ended up being able to hang out with probably eight or nine African American students at my gallery opening the other night . . . [I said,] “I shot these. Let me tell you about it,” and I told them the whole story. They asked a lot of questions. They thought [the story and photos] were really poignant too. I was asking them if they could ignore, and they were like, “Yeah, probably now after seeing this” . . . Given the current political climate, too, it was kind of me putting [the photos] out there, going, “Let’s not forget all the bullshit stuff that’s gone on in our region.”

What is it about your influences’ images that makes you have a visceral, emotional reaction?

A lot of times it’s the fact that they got access. The more posed the portrait . . . I don’t know, those are kind of boring. Most of my stuff is like grabs. They’re real quick . . . There’s a Kings of Leon shot of those guys, like second show in. That was the only picture I took of them the whole time they were visiting me to talk about what they wanted to do. I just snapped a picture in my office. That’s what that is. [In] the Lenny Kravitz picture [from the exhibit], he’s in the bathroom getting ready to go on The Ellen DeGeneres Show, and I’m like, “Let’s shoot a picture,” and he’s always game for that. I took a camera in there and popped off two frames on a little disposable film camera, and that’s that one. The My Morning Jacket shot, they’re staring at the photographer shooting their record. I shot from the side. They ended up using mine in the Okonokos record and not the one by that guy they hired.

It seems like you’re really all about the moment, then.

Yes, the candid. I’m a street photographer by nature. I carry a rangefinder around New York and I will shoot anything, anybody. As long as I’m a fly on the wall and I’m not being obnoxious. I like that grab and run, man. I don’t like these long photo shoots with people where you’re tweaking the light. I’m not that guy. I’m not a studio-light-pose-with-multiple-assistants kind of photographer. There’s obviously a gigantic place for people that do that, it’s just not what I’m interested in. I’m interested in forgetting I have a camera around my neck [as] I’m going about my day and seeing something and saying , “Oh, I’ve got a camera around my neck.” I think Danny [Clinch] shoots that way a lot. He does the big pose stuff, but his candids . . . This is a Danny Clinch right here [motions to a photo of Tom Waits].

I mean, one day maybe I’ll get a shot like that . . . That’s what keeps me coming back. Everybody tells me my shots are good and all that, but I don’t have that yet. My goal is to get that.

Is there a similarity between catching a picture at that moment and maybe catching an artist that you’re working with at a key moment in their life? Do those two have a relationship?

Oh, man, kind of. Catching that artist and believing, that’s such a timing thing, right? There’s a few times in my life where I was around artists really early, where I came home to my wife and went, “They’re going to be huge.”

Like who?

John Mayer would stay at my house—couldn’t get anybody to pay attention to him. We would put him on the radio in Birmingham, and I would sell his CDs at my record store. I sold his first thousand Room for Squares at [Magic Platter]. It’s one of those things where, I just knew he had the talent. No testament on whether he would end up making great music or not, but I knew that he had a good sense of the connection he was gonna make with fans . . . There’ve been a lot of other bands. I was really on Coldplay. Radiohead, we were a huge influence on [their sales] with the Coalition of Independent Music Stores and kind of breaking OK Computer. You know, there’s been these incidents where we just knew it was the best thing ever, and we kind of led the way.

As a music industry veteran, you’re in a very coveted position where you can look back like that. What advice do you give to people who want to be in your shoes?

I’m just telling kids to get really proactive. If you’re at a dead end where you’re at an internship and no one knows your name and you’re going to get coffee and taking out the trash, I say, “You know, maybe that’s freshman, first-quarter thing, but don’t ever do that again. Get a job.” If you find an internship you really like, tell them you want to come back for free after the internship’s over and just come in after school and help out and worm your way into being so valuable they hire you. Belmont and MTSU are both incredible schools, and some really smart people go there. Some people are wealthy, some people are dirt poor. I don’t find that there’s a big difference in their desire.

There’s nothing better than learning from your own mistakes, you know? Because I’ve always been an entrepreneur and running my own thing. It’s never scared me to lose something because I always know I can go find something else and do something else . . . You don’t know shit, you don’t walk [into a job] acting like you do, and learn. Learn, learn, learn. Absorb, absorb. Go out and see shows, meet people, network, know everybody in town. That’s how you get gigs.

Going back to Southernacana—what do you want them to take away from the gallery? What sort of conversations do you want it to inspire?

You know, the same ones they’re having straight to my face, which is, “Wow, this is really cool, great work,” “I love your pictures,” “I hate your pictures,” “What is this all about?” “What does this mean?”

It was kind of funny because one of the pictures I’ve got there, I was walking on the bridge out there at Natchez Trace, and was gonna be a goofball and shoot a moving car from on top of the bridge. I was gonna shoot straight down, that was my big vision for walking way out on that bridge [laughs] . . . I was walking down that bridge, and there, right on the rail was “So long world” written, and I just [makes clicking motion] and kept walking. [At the gallery opening] people would say, “Did you write that on there?” I said, “No, I wouldn’t even think to write that on there” . . . I’m not staging shots—it’s just not what I do. But I thought that was kind of interesting that they would wonder that. I would have people sit [at the gallery] and stare at it for a long time . . . People were standing there talking about that, about how horrible it must be to be standing there, you know, contemplating suicide. [Asking], “Is it a jumper bridge?”

The conversation around some of these pictures has just been great . . . I was getting asked a lot of questions by people, you know, dragging me over to a picture like, “Tell me what this is. What is this? Why did you shoot this?” That was really gratifying . . . Hopefully they’re pictures that cause conversation and enlighten people. [Hopefully] people find some things humorous or they walk away from it feeling like they’ve seen some art, you know?

Suggested Content

Chelsea Kaiah James

Why aren't there any ears sculpted onto the presidents of Mt. Rushmore? Because American doesn't know how to listen. - Unkown

Contributor Spotlight: Dylan Reyes

When I create, I often think of what Johannes Itten said, “He who wishes to become a master of color must see, feel, and experience each individual color in its endless combinations with all other colors.”. I’m also inspired frequently by love and loneliness and want folks consuming my work to be encouraged to start paying attention to the little details in everyday life, appreciate the simple things, and let them eventually inspire you! Ultimately, I’m just trying to become a mother fuckin master of color.

Secondhand Sorcery

A look inside the beautifully cheesy world of Crappy Magic