A sultry Mississippi midsummer, 2012. Caroline Randall Williams was indulging in a guilty pleasure: reading British tabloid rag the Daily Mail. Oh, she knows. “I claim that. And I’m not ashamed of it. But I also—I know what that looks like. I don’t smoke cigarettes, I don’t go to tanning beds. But I do read the Daily Mail every day.

“Every so often, they do publish things that are true and interesting,” Randall Williams laughs. “And the way they do the titles is so glorious.” The author, poet, Shakespeare scholar, and Nashville native stopped at a headline. “I came across this article: ‘Was Bard’s Lady a Woman of Ill Repute?’ I go, ‘Yessssssss. Yes! Was Bard’s lady a woman of ill repute?!?’ Anything scandalous to do with Shakespeare. I love things that humanize him . . . I love the idea that Shakespeare fell in love with a brothel owner somehow!”

The clickbait title would lead Randall Williams on a fertile literary journey, and even beyond her pages to an eventual collaboration of her words with dance and music—and a powerful reckoning of her identity as a black woman.

The accompanying article laid out the research of one Dr. Duncan Salkeld, an expert in paleography, or the study of handwriting. Salkeld was documenting Elizabethan-era prison records, more or less illegible to anyone without his expertise, when he discovered a connection between Shakespeare’s troupe and a brothel owner named Black Luce (an archaic spelling of Lucy).

“Black Lucy, aliases Lucy Easte, Lucy Baynum. Black Lucy was a brothel owner, simply put, and likely a woman of Moorish descent,” Randall Williams explains. “She was really successful, and she was never arrested . . . People were constantly getting arrested on her premises—and she was somehow never there. I just found that narrative so empowering and intriguing.”

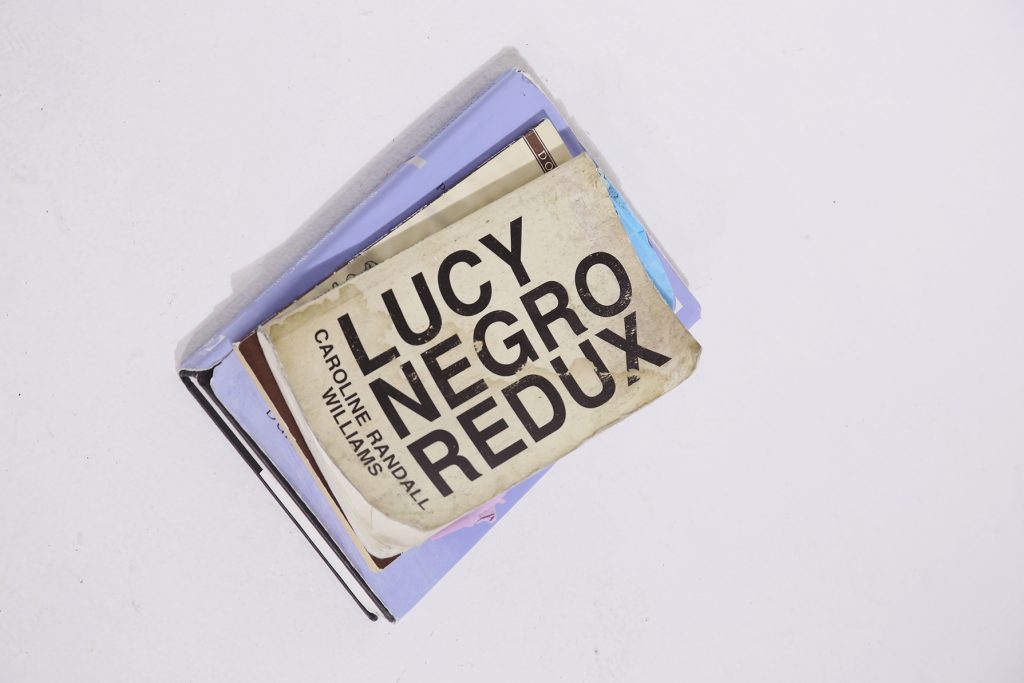

Caroline Randall Williams has invited me to her home, a breathtaking mansion on Blair Avenue owned by her parents, author Alice Randall (The Wind Done Gone) and historian David Ewing. After decades away, she’s returned as an adult to her childhood home (in a piece of multidimensional folk art hanging in the dining room, her smiling family is driving a car toward their home on the hill). Randall Williams and a roommate live here along with Sebastian, her Petit Brabançon Brussels Griffon. Between occasional barks and growls from the minuscule furball, we’re discussing Lucy Negro, Redux, her book of poetry, newly released by Third Man Books, that takes Black Lucy’s story as a jumping-off point for an exploration of otherness, black femininity, and sexuality.

Could Black Lucy be the famous Dark Lady mentioned in Shakespeare’s Sonnets? “Up until Duncan came across this record, people had speculated,” Randal Williams informs me. “People had known about Black Lucy, and scholars have long been hunting for the identity of the Dark Lady in the sonnets, in history . . . Up until Duncan’s discovery, there hadn’t been any document that put Shakespeare and/or anyone immediately attached to Shakespeare and Lucy in the same place, to say, Oh they definitely knew each other.”

What Dr. Salkeld found in the 16th-century prison record was documentation of the arrest (at Black Lucy’s brothel!) of an actor from Shakespeare’s circle. Randall Williams flipped. “I’m like, ‘This is crazy! Why is no one freaking out about this?!? Oh my GOD!’” She pauses, takes a breath. “And then I remember that the intersection of people that care about Shakespeare deeply, black woman-ness, and also read the Daily Mail is really limited.”

Our laughter fills the room. Even with that unlikeliest of Venn diagrams, Randall Williams wondered, “Where’s the parade? Where’s the party? Where’s the ringing of the alarm?” Since no one else seemed to appreciate the dramatic news, she applied for, and was given, a small research grant through her MFA program at the University of Mississippi. That spring, she flew to England to meet Salkeld.

Strolling through Clerkenwell, the London neighborhood where Black Lucy and her ladies walked the streets, Randall Williams found herself in their world. “I was at that point totally captivated,” Randall Williams tells me.

Will and Lucy were everywhere. “She was here. She was here. She was here. And he was here. And now I am. And I’m now part of the story of these stones, a story that began before them, but that they added to and that now I’m getting to engage with explicitly.”

When Shakespeare wrote, in Sonnet 132, “Then will I swear beauty herself is black,” what if, Randall Williams suggests, “he meant black. Which he probably just did! Shakespeare’s a very intentional writer. He has all of his words.”

Was his beauty the Moorish brothel owner, Black Lucy? Thanks to Dr. Salkeld’s research, it’s clearly possible. But does the truth matter? Lucy Negro, Redux exists. It is a real book of poetry. Black Lucy was a real person. Beyond that, Randall Williams explains, the lack of any further details about Black Lucy works in the poet’s favor. “It’s sort of a weird mercy of history that there’s not more,” she posits, “so I can imagine her into existence in a way that feels right to me.” Black Lucy is: whatever the poet needs.

Randall Williams recalls the way her deep dive into Black Lucy gave her a new way to see herself. “Thinking about her caused me to ask so many questions about my own sense of my body in the world and the way people experience it. My color in the world and the way people experience it. The way I experience people experiencing it.” She adds with a grin, “Lucy is in that way sort of an avatar for otherness, and for claiming it positively and celebrating it.”

“I am the descendant of slave owners and slaves,” Randall Williams tells me. “I don’t have a white side of my family, a black side. I have a lot of history of plantation rape in my family. But that’s always been a meaningful truth in my life, that’s never been mysterious to me. I was raised knowing that.” She lays out her family tree—its rotten roots will be sadly familiar to some. “I am the child of two black people, the grandchild of four black people, the great-granddaughter of seven or eight black people, depending on who you ask. And if you go back one more generation, the majority of my great-great-grandfathers are white men who took advantage of their help . . . [that’s] why I exist, in the color and body that I do.”

The history of white plantation owners lusting after their chattel, disgusted at their own forbidden desire is, Randall Williams points out, “very real to black Southernness and femininity. But it’s all up in Shakespeare! And that is what was crazy for me. To look at those poems and say, ‘This thing that I thought was this peculiar hardship of my ancestresses in this country has a narrative that was articulated by my actual already-favorite writer!’”

Caroline Randall Williams’ first-ever printed piece was a February 2013 cover story on Justin Townes Earle for this very magazine; shortly after, Ampersand Books released the first edition of her debut poetry collection, Lucy Negro, Redux. Lucy Negro is fiery, complex, and passionate. The book tears across centuries, pulling the reader into the swirling dark waters of Black Lucy. Lucy washes over you, crashing wave after wave, verse after stanza. The poems smell of sweat and sex and stones. Bits of songs ripple through the pages: field hollers, Etta James, juba handclaps, children’s rhymes. Lucy, Lucy where you been?

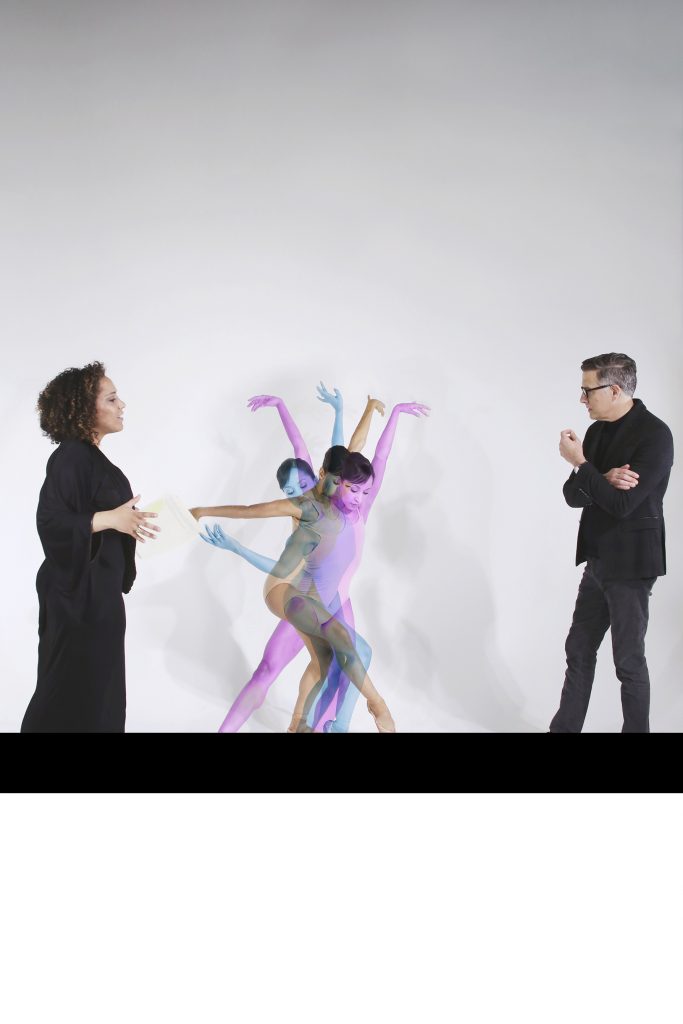

The musicality of Lucy Negro, the bluesy sway and stomp, is certainly part of what captivated Paul Vasterling, the artistic director of the Nashville Ballet—which brings us to the unexpected second chapter in the life of Lucy Negro, Redux. Vasterling is a voracious reader and consumer of artistic media, and everyone in his sphere knows it. When a board member of the ballet happened to catch a certain poet reading from her new book, Vasterling ended up with a copy of Lucy Negro, Redux.

Between the Nutcracker and prep for a gala to celebrate his twentieth year with the company, Vasterling finds time to answer my questions via email. Reading Lucy Negro, he was hooked instantly. “I started this one weekend and almost immediately saw that it could be something—a film, a play maybe,” he writes. “So I called Caroline to ask to meet. When we did, I asked her if she would consider it being a ballet.” Vasterling understood the emphasis the work placed on black identity and womanhood, and so he also asked Randall Williams “if she thought that I, a white man, would be the person to choreograph and direct it.

“She said yes,” Vasterling continues, “and then pointed out that a secondary but large part of the story that appears in her poems is that of the alleged relationship between Shakespeare and the so-called ‘Fair Youth’ of the sonnets. Shakespeare wrote two-thirds of the sonnets to this young man and the other third to the ‘Dark Lady.’ Being a gay man who has lived my life and my relationship in various levels of ‘outness’—and certainly feeling a strong sense of otherness—I saw my fit for this, a rightness about this project coming into my spectrum at this moment in my life.”

The Third Man Books edition of Lucy Negro, Redux includes a conversation between Vasterling and Randall Williams, as well as a condensed libretto of Vasterling’s choreography and photos from early developmental rehearsals. The choreographer notes: “I think ballet, and dance stories in general, lend themselves to this slow burn of understanding. Caroline’s book is a narrative, but one that is not quite linear—I found that I understood the story slowly over the period of the reading.”

Randall Williams remembers her response when Vasterling reached out. “I said, ‘I need to meet you and see if it works.’ And then, ‘Do you have a dancer?’ And by ‘Do you have a dancer,’ I mean, ‘Do you have a woman who’s world-class?’ Because the talent alone comes first, right? But then, ‘Do you have somebody who’s world-class, and also a woman of color who can embody this?’”

She adds, “It’s funny, knowing Paul now, he never would’ve brought this up if he didn’t have one. But you know, sometimes, people are: Just. Not. Woke.”

Nashville is blessed to have a spectacularly talented prima ballerina in our local ballet company. Most importantly for this particular role, Kayla Rowser is also African American. “I would never have even come up with this idea if Kayla had not been in Nashville Ballet, or if she had not been at her current very high level of artistry,” Vasterling explains. “As I was reading Caroline’s book, I literally saw Kayla as Lucy. And as I think about it now, I see Kayla—the way she moves, the way she expresses herself in movement. She informs the way I develop this character in my head. All of this will inform the way the movement for the piece is developed.”

Rowser deserves an entire write-up all to herself: she’s not only a sublimely beautiful dancer and person, she’s also a deep thinker who’s carefully considered what it means to be a black ballerina. It shouldn’t be rare, and yet it is. It shouldn’t be revolutionary, and yet. I visit the ballet’s studios, tucked away in West Nashville, for a quick chat. They’re dancing when I arrive; they’re always dancing. They rehearse 9 a.m. to 6 p.m., five days a week, and most of them have second jobs, teaching or in school themselves. These dancers work their (sculpted) butts off.

Rowser exits the sprung floor in a broad tutu and requests a quick change before we talk. The ballet’s staff gets us all set up in a conference room looking out on the main hall. I ask Rowser about Black Lucy and she beams. “I’m excited to represent a character of strength, of ambition, but also a black woman. And to have all of that together, and to be able to portray that through my art form, is really, really, really exciting!” Rowser says with a laugh. “I’m obviously a black woman, but my characters have never been black women.

“I feel it’s going to be really rewarding,” she continues, “but also emotionally challenging . . . It’s very different, and I’m very excited for the challenge.”

If she wasn’t up for facing difficulty, she wouldn’t be here, as the ballet’s principal dancer. She’s a black woman in an art form that’s historically whiter than driving a Prius to a farmer’s market. That has to be tough, right? “You know, on some days, the weight of that feels pretty heavy. And other days, it doesn’t. But I think I’ve been fortunate enough in ballet to have people who have seen my strength as a dancer and as an artist, and they’ve also seen and recognized the fact that I’ve defied some things.” She laughs, big and brightly. “Based on the textbook, I shouldn’t be doing roles I’m doing, I shouldn’t be as successful in my career as I am.

“But there are so many nuances,” Rowser points out. “Even from trying to find shoes that match my skin tone. And the costume shop, they so graciously send off tights to be custom dyed for me—but I can’t wear those in rehearsals, because they don’t exist on a shelf. So even little things like that, they’re huge . . . To say that there’s not a lot of weight in being a black woman in ballet would be completely false.” Still, when Rowser considers her skill level and her career trajectory, she’s certain: “The time is now to do a ballet like this.”

The final ingredient in this potent creative stew is the music—ballet isn’t so great without it. Vasterling and Randall Williams agreed that it made sense to seek out a young, talented black woman, and my oh my did they ever find one. Scoring the ballet and performing live in February is Rhiannon Giddens, the recipient of a MacArthur “Genius Grant” and winner of the Steve Martin Prize for her expert banjo skills and her reclamation of old-time string band music. More specifically, she takes the music back to its roots—to spirituals, field hollers, and gutbucket Delta blues, before white folk recorded and commercialized it. Before Elvis. (Despite attempts at scheduling a video chat, Giddens and I unfortunately fail to bridge the Atlantic Ocean and the time difference between me in Nashville and her in Ireland before press time.)

On the whole, Lucy Negro Redux is remarkable. There are now three supremely talented, young, black female artists working on the project, all of them working in spaces traditionally dominated by whiteness: the scholarly study of Shakespeare, ballet, and old-time music.

And, most incredibly, this is all going down here. “This is just greater than the sum of its parts, in terms of the narrative of the collaboration itself, of all the things that had to come together, and of the goodwill of people who want a thing . . . And this is happening in Nashville!” Randall Williams nearly screams with delight. “Can you believe that? Little old Nashville, with its thirty-year-old ballet company, is the city where this gets to happen?! Where we’re writing about Shakespeare’s Dark Lady, [alongside] Grammy Award–winning musicians. And everything is happening in Nashville! It’s amazing.”

Lucy Negro Redux is showing at TPAC’s Polk Theater from February 8 to 10.