Sinclair is in the middle of telling me how she left home and moved to Nashville when she drops a cigarette in her lap and derails the conversation. Standing quickly to survey the damage, she sees that the lit end luckily didn’t have enough time to burn a hole in her fabric, but it’s left a clearly visible spot of ash on her white sweatpants that she can’t wipe away.

“Jeez, my wife is going to be disappointed about that. Don’t tell her,” she says seriously for a second before breaking into a laugh. “No, she’ll definitely notice.”

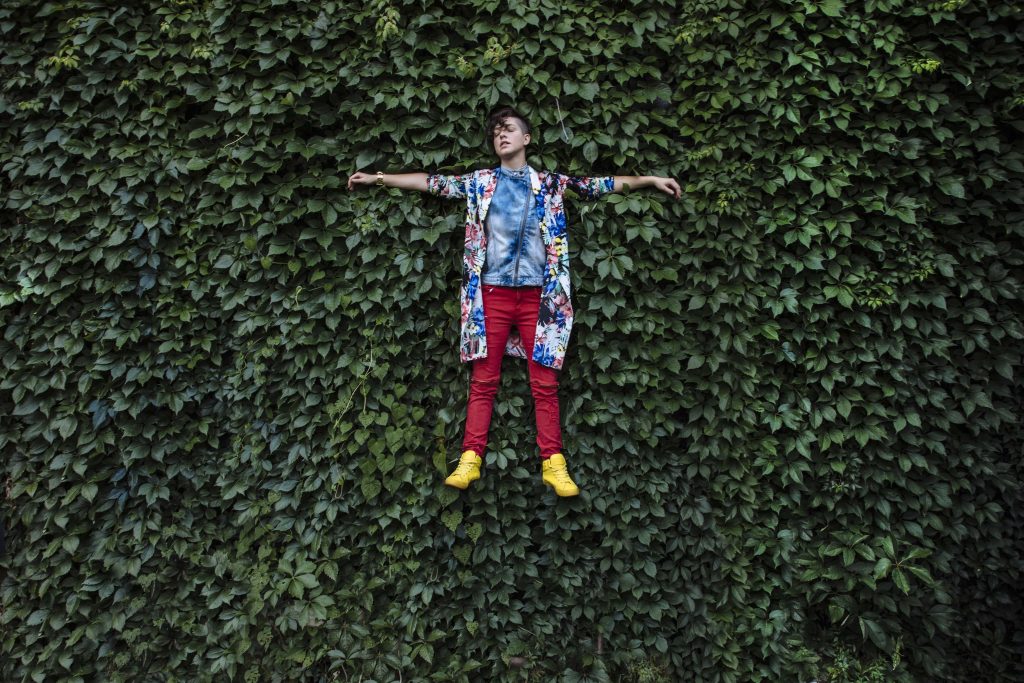

Seated comfortably at the dining table in her one-room apartment downtown on Rolling Mill Hill, Sinclair stands out in her surroundings. Save for the flashy yellow pumps on her feet, she’s dressed in all white. The apartment, on the other hand, is filled with a vibrant array of colors and textures. It was eclectically decorated by her other half, a painter named Natalie. There’s a bright orange couch, a blue and green watercolor wall, and a sleek-looking rocking chair with a fuzzy white thing that might either be a pillow or a blanket. On the other side of the table, an unfinished painting sits on an easel.

“Where was I?” she asks, brushing her pants one last time before realizing the futility of her attempt and moving on.

Sinclair was born the sixth of nine kids to musically minded parents in a tiny town in upstate New York called Madrid. Raised in an extremely conservative and religious household, she was homeschooled alongside her siblings from kindergarten to twelfth grade. Her exposure to other beliefs and worldviews was limited, but her musical education certainly was not. When she was only five or six, she heard her older sister playing a famous Bach fugue on the family piano, and her passion was ignited. According to her parents, she climbed up on the piano bench herself a few days later and, using only her talented ears and trial and error, she found Bach’s melody.

“Music was running around my mind at an early age,” she says.

Like any sensible guardians, her parents immediately enrolled their Bach-playing six-year-old in piano lessons. A few years later, she took up classical guitar, which she says came to her even more intuitively. Throughout the rest of her adolescence, she learned various other instruments ranging from the cello to the mandolin, keeping a strong focus on guitar and even competing in classical tournaments around the country. As someone who says she’s never had a “real job,” she found ways to make money by teaching lessons and even touring with a band she founded alongside her brother. But despite her technical appreciation and education, it wasn’t until faced with a crisis of identity that she began to fully appreciate the emotional power of music.

Though she says she knew she was gay in some regards since as early as eight years old, Sinclair’s religious upbringing—her father was an evangelical Christian pastor at a nondenominational church—forced her to spend the majority of her adolescence praying that God would make her straight. By the end of her teenage years, however, reality began to set in, and she started to finally face the fact that she couldn’t change who she was.

“That was when I was like, I don’t think I can live without being able to express my love for someone,” she remembers. “I think that’s a very important part of being a human.”

Terrified and depressed, she finally came out to her family shortly after her twentieth birthday, though their response didn’t do much to alleviate the fear or the sadness. For nine months, she continued to live at home in an environment that lacked acceptance or understanding. In those moments when her parents would actually face the reality of her sexuality, they’d insist that she “bear her cross” and remain celibate for the remainder of life, an expectation that wreaked havoc on Sinclair’s mental health.

“I didn’t want to talk to anyone, didn’t want to eat, didn’t know how to sleep,” she says before taking a long pause and continuing. “I was definitely suicidal for a few months.”

Without any other outlet to process what was going on inside her, she began writing songs. Music became, for her, a lifeline. It was not only a way of expressing herself, but also a way of moving forward. For the first time in her life, the songs she was writing were cathartic and therapeutic. Sadly, that authenticity didn’t go over too well at home.

Sinclair remembers one painful night in particular: she was playing one of her original songs for her sisters and one of her friends when her mother walked in during the middle of the performance and cut her off.

“She said, ‘You can’t play that here. I don’t want to hear that again,’ and then sent my sisters up to bed,” Sinclair says, looking down at her cigarette. “Man, that killed me, that fucking killed me.”

On the eve of her twenty-first birthday, Sinclair loaded her instruments into a car that she had bought with cash from her grandparents and left her hometown. She knew she wanted to pursue music but feared bigger cities like New York and L.A. would swallow her whole, so she set out for the thousand-mile trip to Nashville, Tennessee. It’s a drive she’ll never forget. Having grown up heavily sheltered, she had only just discovered Michael Jackson, and she still remembers the feeling of cruising southward with the King of Pop’s greatest hits blaring in the car speakers. It was the sound of rebirth.

“Everything felt completely new. It was exhilarating,” she says. “I felt like everything in me was being reset.”

The first year of Sinclair’s new life in Nashville wasn’t all that easy. She moved from Antioch to East Nashville to Brentwood all within a handful of months. She paid rent by playing bass or cello for other bands and struggled to gain recognition at writer’s rounds around town. Still, she continued pouring her experience into honest new songs. In the fall of 2014, she finally released Sweet Talk, her debut EP, and for the first time she found herself meaningfully connecting with fans across the country. “This Too Shall Pass,” a song inspired by her troubles back at home, resonated unexpectedly well with listeners. She still gets messages from fans who say that song has helped them through their own struggles and depression.

“The listeners are everything,” she says, telling me about a letter she received two days ago from a girl dealing with her own coming-out process. “Every time I want to give up, I’m like, Oh yeah, I owe it to myself and to people to release what I’m going through.”

Her second release, last year’s three-track CLR BLND EP, saw her experimenting with new, bigger sounds, this time as her own producer. Having taught herself how to produce by watching others in the studio, she went for a more electronic pop sound that led to larger exposure via outlets like Teen Vogue. Now, as she prepares to release new music this fall/winter, she says she’s excited for listeners to hear a sound that’s less curated and a little more raw.

“If Icona Pop and Michael Jackson and Sting had a baby, it would be Sinclair right now,” she says of the new material, some of which fans can expect to hear when she performs at Pilgrimage Music Festival in Franklin this September. “I’m getting back to more of this world-funk and dance.”

On April 12, 2012, almost a year after moving to Nashville, Sinclair was getting ready for a weekly get-together with friends and friends-of-friends when she heard a knock at the door. Natalie had arrived early to the party, and when Sinclair opened the door, she was immediately blown away. It was Easter Sunday.

“It’s like, ‘Yes, hallelujah!’” she says with a shout. “I didn’t know necessarily right then . . . but just saying hello, I could already feel so many amazing things about her.”

Overwhelmed by her attraction, Sinclair sat Natalie down to tell her about her interest a couple of weeks later, only to find out that Natalie had been interested in women her whole life but had always been too scared to start something. The two went on their first date, and a year and a half later, Sinclair popped the question on New Year’s Eve in Brooklyn. They were legally married in San Francisco in June 2014, barely a year before same-sex marriage was legalized across the country.

“I’m the luckiest with my wife,” she says. “We’re human. We’ve had plenty of downs . . . but I’ve had five years now, and it’s been the best.”

Two years ago, the happy couple held a wedding celebration in Nashville for their friends and family. Sinclair invited her eight siblings and her parents, but none came, a move she says wasn’t all that surprising. Though she thinks they hope good things for her and her music career, they don’t really listen to the music she makes either. In fact, she says no one in her family is super supportive of anything she’s doing at the moment, a statement she makes seemingly without anger or resentment.

“I think I’m finding a way to just say, ‘There’s maybe hope that things will end up being a little better than they are,’” she says. “My hope is just to be somewhat aware of what each other is doing, because I don’t think it’ll be much more than that.”

Though she says she will never stop caring about or loving her family, Sinclair has learned to distinguish between what she calls her given family and her chosen one. Since coming to Nashville six years ago, she’s met and surrounded herself with people who have chosen to love her exactly as she is. In that time, she’s learned that life is all about community and finding the right people to help you thrive.

“Family is just luck or unluck,” she says. “But when people choose you, they are picking a battle. They are making a promise . . . and right now, that’s even better. It’s a more beautiful thing.”

Sinclair plays Pilgrimage Saturday, September 23.