Suffragists

Alan LeQuire describes heroic scale in technical terms: “That means life-size plus 20 percent.” Most Nashvillians are familiar with LeQuire’s larger-than-life works. This is the sculptor that brought Nashville Athena Parthenos, who holds the life-size Nike in the palm of her hand. The figures of Musica are fifteen feet tall and the entire sculpture ascends to forty feet. The colossal heads that make up his recent Cultural Heroes are each the size of a small person. Life-size plus a fifth may seem modest, but in LeQuire’s latest public art commission, size combines with timing and placement to tell a Nashville tale of truly heroic proportions.

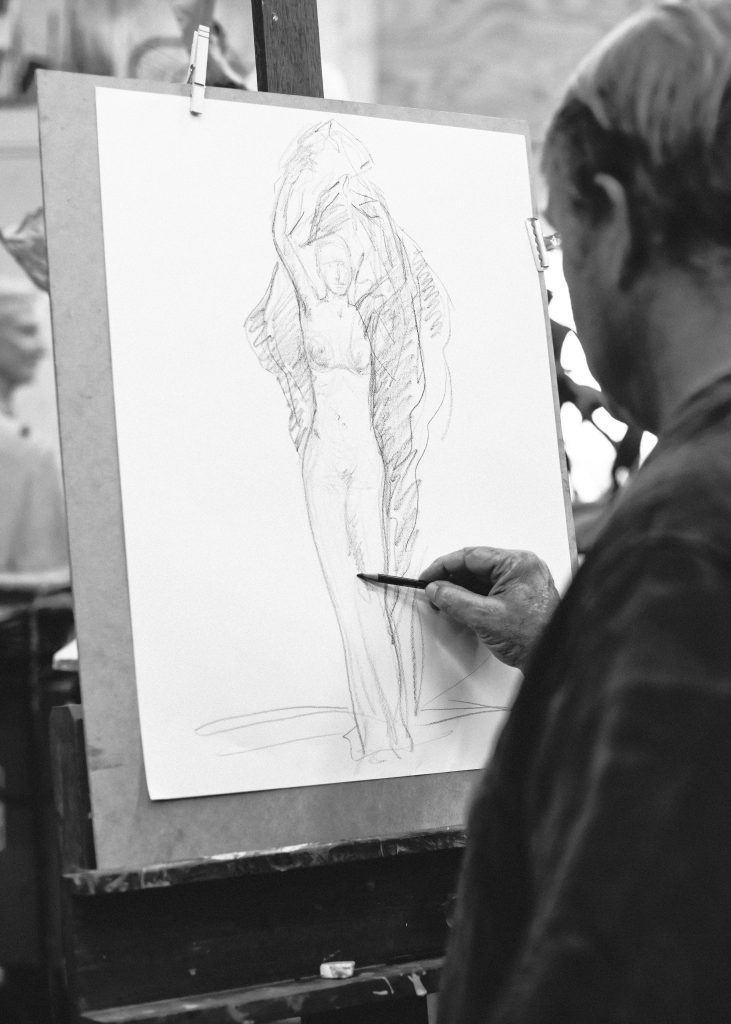

The soft-spoken artist tours me around his studio on Charlotte Avenue, a space animated by dozens of miniature clay studies, works in progress, and finished pieces that watch over the apprentices, interns, and gallery managers that share the workspace. We pause on the molds of three purposeful women, about seven feet tall, eyes forward over our heads. They are suffragists Anne Dallas Dudley and J. Frankie Pierce of Nashville and national suffrage activist Carrie Chapman Catt. The women are part of LeQuire’s latest civic contribution, Tennessee Woman Suffrage Monument, which consists of heroic scale portraitures of five women,marching together on a pedestal, in bronze. A future memorial plaza in Centennial Park will house the figures (as of August 26, they have a temporary home at another Centennial Park location). “The other two [Sue Shelton White of Jackson and Abby Crawford Milton of Chattanooga] are at the foundry . . . I’ve never seen them all together, so I’m a little bit nervous,” LeQuire tells me. But these women already tell their own story.

In August 1920, Nashville was thrust into the national spotlight as Tennessee legislators were called to a special session to vote on whether (or not) to be the thirty-sixth (and deciding) state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment, determining that women should have the right to vote. A movement seventy-two years in the making, women’s suffrage activists organized in Nashville to influence lawmakers against a (familiarly) kicking and screaming conservative opposition. The “antis”—businessmen, politicians, several prominent women, and other members of high Southern society—decried the end of civilization. They harassed and bullied the suffragists; they courted the media with the opinion that voting compromised femininity; they slandered the suffragists as ugly, bitter “she-males;” they threatened violence. But the suffragists prevailed. Tennessee ratified by one vote. The deciding vote came after one legislator’s mother wrote a letter that convinced him to change his mind at the last minute, which effectively ended his political career (as if you need any more reason to vote this year).

Nearly one hundred years later, 2016 represents a landmark year for women in politics. This year has witnessed the first woman mayor in the city of Nashville and the first woman presidential nominee from a major party on the national stage. Still, less than one in ten U.S. public monuments are of women. “I am motivated to bridge the gap between history and the present,” says LeQuire, “so the timing is right.”

The placement is also right. In heroic scale, the Tennessee suffragists are real, approachable, historical figures—not gods or muses. But outside the Parthenon, under the eye of Athena, the suffragists also evoke the heroes of antiquity. They are excellent: strong in their collectivity, inspiring in their daring, and successful in battle. The suffragists are recognized and honored: they won the right to vote in their own lifetime so that the rights and demands of full citizenship could live beyond them. They are renowned: cast in bronze, they and their victories will be immortalized here among the ancients.

But the suffragists are animated in the present as well. Slightly larger than life, they remind observers that protest is a heroic practice and will forever define American politics. They remind us not to take for granted today what was bitterly contested in the past. Indeed, it is here, outside the Parthenon, in the Athens of the South, that the monument also subverts the Southern, masculine cult of antiquity by presenting five powerful women as the heroines of contemporary democracy.

Studio

LeQuire describes his work as “based in the figurative tradition,” and he draws artistic inspiration from classical Greek, Egyptian, and Roman sculpture (“mostly Greek”). He’s always liked the idea of sculpting real people, but not in a “realist” sense. Instead, he strives for magical realism, or “making the inanimate animate,” he says. “That is the fundamental mystery of art [sculpture] . . . that is what fascinates me.” It is fair to say that Tennessee Woman Suffrage Monument comes to life, but I find LeQuire a bit modest, like there is still more depth to how he conceives his work. For example, scale refers to size, but the heroism of the Tennessee Woman Suffrage Monument works at the intersection of time, space, and political consciousness.

That epic quality can be found in all of LeQuire’s major public works. Musica is much more than a “Music City” tribute. Musica is latin for “art of the muses,” which the nine figures represent. The statue at the center of Buddy Killen Circle was always meant to be a fountain as well, symbolizing the source of creativity—the earth opens up and water bursts out, while the muses ascend upward from the omphalos. As such, Musica is yet to be finished.

The iconic Athena Parthenos is the largest indoor sculpture in the United States at forty-two feet tall, and it took nearly eight years to complete her. For all of modern technology, that is only one year less than it took the ancient sculptor Phidias to complete the original version. Perhaps we need not dig for any further significance in Athena though. Sherepresents a fascination with and a mastery of the past, but it is less about the goddess herself than it is a sculptural and philanthropic feat. It is also the work that marks the culmination of LeQuire’s classical training in sculpture and the one that made him Nashville’s preeminent public artist.

LeQuire maintains a public presence, and at this stage in his career he is a willing source of learning for other aspiring artists. More importantly, he is responsible for bringing this art to Nashville. Figurative sculpture in the late 1970s was so out of fashion that LeQuire found few formal training opportunities. He enrolled in European art schools in France and Italy and sought out apprenticeships with masters Milton Hebald and Puryear Mims before attending grad school in North Carolina in the early ’80s. Now LeQuire’s knowledge attracts students from around the world. When I interview him, I meet an intern from France and a local apprentice who insists that LeQuire hosts the longest-running open studio with live human models in Nashville. His gallery/studio has been a Nashville destination for decades.

Statues

LeQuire is a Nashville native. “He’s the most native there is!” his apprentice points out. I think she is taunting me (or the publication, rather). She means something like while Nashville has produced artists of comparable stature in the past, LeQuire is unique in his ability to have built an art career (other than music) in Nashville alone, before it was cool, and he remains committed to the place that his artworks help define.

To fully capture LeQuire’s work and career, it is indeed relevant to point out that Nashville is an off-center, Southern city, far from the galleries, critics, and publications that can make or break visual artists in places like New York City. But like many other notable Southerners, LeQuire had to leave to return as an artist. By the time he completed Athena, he was a big fish in a small pond. He then made compulsory visits to New York but realized that (even as a successful artist) affording rent and having a studio practice there were entirely different realities. Further, he says, “Nothing that was going on in New York [then] was interesting to me.” He already had commissions and notoriety in Nashville, and now he gets to live the lifestyle he wants and give back to the city that has always supported him.

In fact, when LeQuire lists his earliest patrons, some other connections arise. They were all women: Anne Potter Wilson, Grace Zibart, Dr. Mildred Stahlman, and Anne Roos (along with her husband, Charles). “I have always tried to represent women in my work,” LeQuire says, when asked about his personal connection to Tennessee Woman Suffrage Monument. I look around his studio: also all women, including his wife, Andrée, who plays a major role in the making of Nashville. She is responsible for the nonprofit foundation that has recently secured funding for the much-anticipated fountain that will finally complete Musica.

On my way out, Mrs. LeQuire is eager to show me video renderings of this fountain. No doubt its construction will tie up traffic for some time, and long-time and recently arrived Nashvillians alike will disparage the changes. The LeQuires also wish that Nashville would slow down. But their name is a fixture here, almost larger than life, helping to animate a rapidly changing place by connecting its past, present, and future.

Suggested Content

Chelsea Kaiah James

Why aren't there any ears sculpted onto the presidents of Mt. Rushmore? Because American doesn't know how to listen. - Unkown

Contributor Spotlight: Dylan Reyes

When I create, I often think of what Johannes Itten said, “He who wishes to become a master of color must see, feel, and experience each individual color in its endless combinations with all other colors.”. I’m also inspired frequently by love and loneliness and want folks consuming my work to be encouraged to start paying attention to the little details in everyday life, appreciate the simple things, and let them eventually inspire you! Ultimately, I’m just trying to become a mother fuckin master of color.

Secondhand Sorcery

A look inside the beautifully cheesy world of Crappy Magic