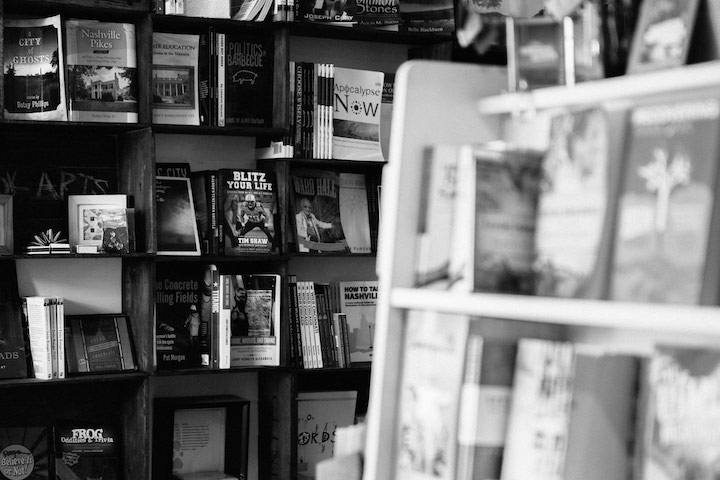

WALKING INTO CHUCK BEARD’S ALL-LOCAL BOOKSTORE, East Side Story, can feel a bit like stepping into a Nashville version of Gertrude Stein’s Paris salon. At any moment, any Nashville author, musician, or artist—many of whom have participated in Beard’s semimonthly live reading/music event, East Side Storytellin’—may walk in to browse, book a slot at the next East Side Storytellin’, or simply shoot the shit.

Such is the case when I go down to the Woodland Street shop the day after Valentine’s. I’ve come to shoot the aforementioned shit with Beard and Susannah Felts, the cofounder of The Porch, a literary nonprofit dedicated to fostering the artistic and professional development of Nashville writers. It’s not long before Kendra DeColo, author of (the very good) My Dinner with Ron Jeremy, pops in and hangs with us for a while. Her visit reaffirms how special a place like East Side Story is: while you can walk into virtually any Five Points bar and talk to somebody about the genius of Gram Parsons or the idiosyncrasies of Fender Twin Reverbs, it’s rarer to find a spot that encourages discussion about literature and writing.

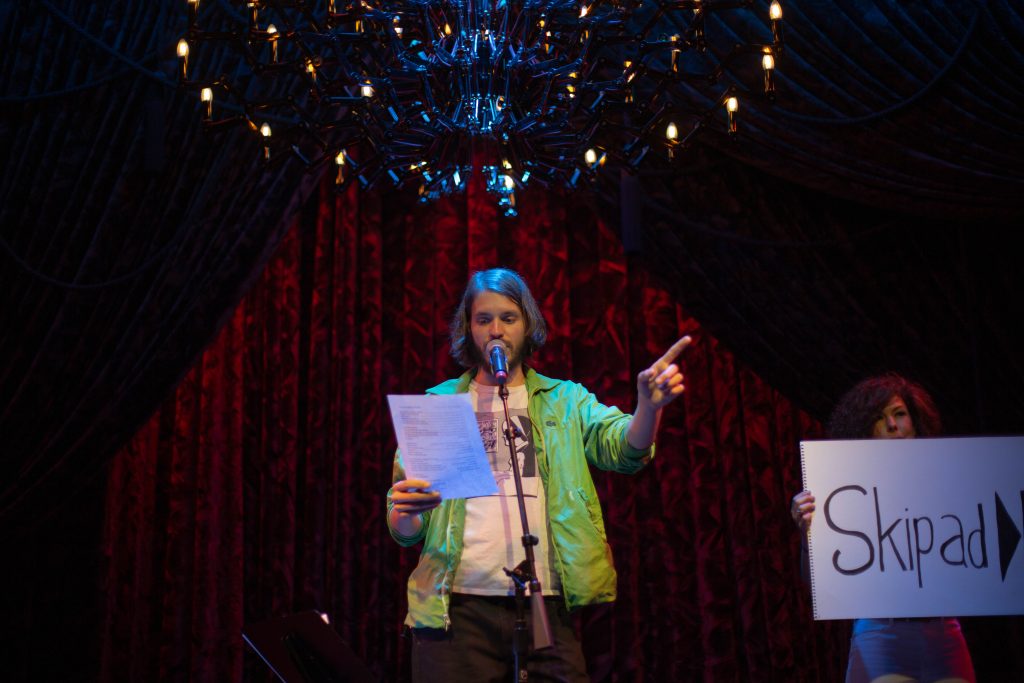

East Side Story and The Porch provide such opportunities, and both organizations are enjoying watershed moments right now. East Side Storytellin’ recently completed its one hundredth (and counting) event at The Post East, and The Porch is gearing up for Mercy & Magic, its third annual fundraiser, which will feature performances by and discussion between New York Times best-selling author Wally Lamb and Americana luminary Mary Gauthier. While both organizations have experienced success over the past few years, they need Nashville’s support to continue growing. I took an afternoon to ask Beard and Felts about the current state of Nashville writing and what’s needed to make literature even more prominent in Music City.

You both work with organizations that aim to make literature and literature events more accessible instead of this snooty, high-art thing. As a city, do you feel like we’re doing better at bringing literature to the masses? Do we still have work to do? What are some of the big hurdles in doing that?

Chuck Beard: I think it’s getting better, just like with everything, the more exposure, the more inclusion, [the better] . . . We live in a day and age where—Bret [MacFadyen, cofounder of The IDEA Hatchery, which houses East Side Story] always says it over here—it’s easy to open up something and sell food or liquor. It’s harder to get people to slow down. That’s the whole art of writing and reading is slowing down and actually thinking. We’re doing more of that these days, because of certain circumstances in the world, and Nashville is doing better and better as far as offering places to showcase people, their thoughts and ideas, their writing or reading, and hopefully it will continue to get better. I’m not saying it couldn’t [grow—that it’s at its peak or anything—but like I said, hopefully we can do it as a community better and better.

Susannah Felts: There’s only room to grow, right? I think we’re doing a lot better in terms of the sheer number— the quantity of opportunities—for people who love books and literature or who are interested in the craft of writing to: (a) find other people that feel the same way, that are their counterparts, and (b) to experience that in a public setting. Maybe that’s the thing. I don’t know, I was thinking about what you first said about the high-artness of literature and making it more accessible. My first thought is like, Do people think of literature that way? I do think there is something about the word literature that just sounds, ya know, fancy pants.

Yeah, I think some people do. The idea of a reading evokes images of cheese and wine sometimes.

Felts: Yeah, I guess it does. That’s something that I really bristle against and I want to tear down. In my mind it doesn’t at this point, just because I feel like I’ve been to so many [readings]. I’ve been going to East Side Storytellin’ and went to countless readings throughout my twenties in Chicago that were not that at all, that were taking place in dive bars and quirky bookstores. It was a very artsy, almost lowbrow sort of thing to do. I guess in my head, I don’t even come at it from that perspective, but I get that people do . . . I guess with all of the arts there’s that sense for some people—that that’s something that they can’t participate in or aspire to. I don’t want that to be the case for writing and for books and literature.

I saw Chuck Palahniuk read at the Southern Festival of Books four years ago, and it was this very cutesy, tongue-in-cheek thing where he came out in a bathrobe and they threw beach balls around. It was fun, but I couldn’t help but wonder: Is this adding to the reading? Do you think that readings lose some of their importance when you put them in a more lowbrow situation?

Felts: Not if the work is treated as important and people are being appreciative and respectful of the [work]—if the work that’s being presented is good and it’s not being diminished in some way. I guess what you’re saying with the beach balls and whatnot could diminish the work. I would never want to do that. We have a reading this Sunday at Jackalope Taproom. It’s called Heartbreak Happy Hour, and we’ve done it for four years. It’s basically a fiction storytelling show. We first did it at Stone Fox for two years, and then they closed down. Last year we had to scramble to choose another place, so we went to Jackalope. It’s in a brewery, so it feels fun and casual and easygoing. The idea is still that you’re coming there to listen to people tell stories and read from their work. I don’t think that diminishes what they’re sharing.

Beard: I was at an art show, a visual art show, a couple years ago at a building off of Chestnut, before Wedgewood and Houston and all that stuff took off. One of the artists, she had a long day, and she was showing in this show and being featured. We were just talking candidly, and she was like, “I didn’t really want to come out tonight. I probably wouldn’t have come out tonight if I wasn’t showing.” It was just one of those ideas that stuck where it was like, if it’s not entertaining to the actual artist [there’s a problem]. It’s hard enough to get people out unless you’re selling beer or food in this day and time, regardless of the reading. I’m not going to spend money just to go hear David Sedaris read from books that I’m just going to read eventually anyway—with the same words. It’s gotta be fun for them. There’s got to be some kind of entertaining aspect other than just somebody reading.

Do you think there’s a literary voice, an identity, shaping around the changing city? And if so, what are its defining characteristics?

Beard: There is a literary identity shaping up. I think it’s an abstract concept and identity in a nebulous form right now, and we won’t know how it turns out or what it turns into until years down the line, depending on how these artists grow and how the city decides to support and invest in it now and in the near future. Whether it’s the events, or the books that are coming out, or Kendra [DeColo] who just came in, or Tiana [Clark], or Ciona [Rouse], or any of the people that are leading the way, these people are going to be nationwide names . . . I don’t want to say names, but it’s one of those things where Nashville is more than just one author. A lot of people that are creatives know that, so it’s a matter of spreading that word and getting people to appreciate the stuff.

One thing I did notice in our coverage of local literature—and then when I talk to people about who they’re reading right now—is that Nashville’s lit scene seems pretty predominantly female.

Felts: How’s the gender breakdown for East Side Storytellin’?

Beard: Fifty-fifty on that, but I see what you’re saying as far as the female [writers here]. I think that that goes into the creative process. Not that everything is about where you are, or what time period you’re in, but definitely—whether it’s politics or anything else—the voice is going to be heard or needed to be heard from that perspective. Again, not that every woman writes about other women protagonists, but at least we’re getting notoriety from Tiana [Clark] and some of the other Nashville poets that are getting a lot of awards and worthy recognition.

They are speaking from a voice and a position that needs to be heard globally—and not just for Nashville. They’re doing a superb job at it, in my opinion. There’s also a layered thing where as far as racially, we need more diversity in the writing—at least for published stuff, not the stuff that’s going on in the workshops and stuff [which is already diverse] . . . Speaking as a white male, we need more diversity in published works from Nashville.

Felts: I would second that. I would say, “Hell, if Nashville gets to be known as the place that champions the female writer, I’m all for it. That’s great.” I’m in that boat, I will go with it.

Do you guys feel that there are adequate places to have readings here, or do you feel like it’s the same spots like The Post over and over again?

Felts: I did want to speak to that . . . because the answer is no. I think decentralization can be a boon for literary culture in Nashville, in that it does force us to get out and pair and partner with other businesses and organizations and sort of attract their audiences and clientele through that cross-pollination. That can be a very useful thing. It can be a way to sort of sneak literature into people’s lives when they’re maybe not expecting it, or kind of [put] it in surprising places, which I think is pleasurable for people. I just simply like the idea of holding hands, or joining forces, with some of the businesses and organizations in town whose work I admire.

[The Porch] dreams of having a physical space that is really a hub for not just readers, but for writers. So there might be some retail, there might be some books being sold or some other sort of writerly objects being sold, but really the purpose of that space is to create an environment where writers can mingle with other writers, come and maybe have work stations where they can work, check out or browse literary magazines, and attend readings. So it’s a space that when writers are coming through town—people from outside of Nashville—they’re like, “Oh, we can set up a reading there.” It would attract talent from other places and kind of put Nashville on the map more as a space that embraces literary culture. We’re really trying to figure out how that’s the next step for us.

Beard: There’s plenty of people with power or real estate in locations here, still even today, that do believe in the arts and are not just about the profit. It’s about combining those things—whether it’s changing a venue and working with different people or just getting the [funds]. You just never know when that one person who believes in what you’re doing, who has the money and power to invest in that, [will invest] and not necessarily want their name behind it . . . There are so many different businesses in town that have silent partners that you would never know about . . . It takes those kind of people. Otherwise, Susannah, [The Porch cofounder] Katie McDougall, myself, other people, we’re still going to find a way. We’re like the weeds in the crack that are going to come out and hopefully bloom into a flower.

The Porch’s Mercy & Magic will take place March 11 at Green Door Gourmet. East Side Storytellin’ #103 will take place on March 21. Cheekwood in Bloom, a children’s edition of East Side Storytellin’, will take place April 8 at Cheekwood Botanical Garden and Museum of Art.

Suggested Content

Write All About It

How literary nonprofit The Porch is giving local writers the tools—and the confidence—they need to share their stories

PHOTO RECAP: Lit Party

We went to the Lit Party on Wednesday night at the Analog at Hutton Hotel. Here's what we saw.