“Four years,” Benny answers. “Six to get rich. But first you’ll have to dress right, you know. And you’ll have to hang out with famous people, you know . . . go to the right parties . . . Then you gotta do your work all the time when you’re not doing that.”

This is a pivotal moment in Julian Schnabel’s 1996 film, Basquiat, when artist Jean-Michel Basquiat asks his friend Benny how long it takes to get famous. It’s also the clip that local visual artist Stephen Watkins randomly shows me on his iPad halfway through our interview. I don’t see the connection between the scene and Stephen’s own story immediately, but I go with it and promise to watch the film later. It isn’t until I’m preparing to leave and thinking back on all I’ve learned over the course of my visit that I begin to understand.

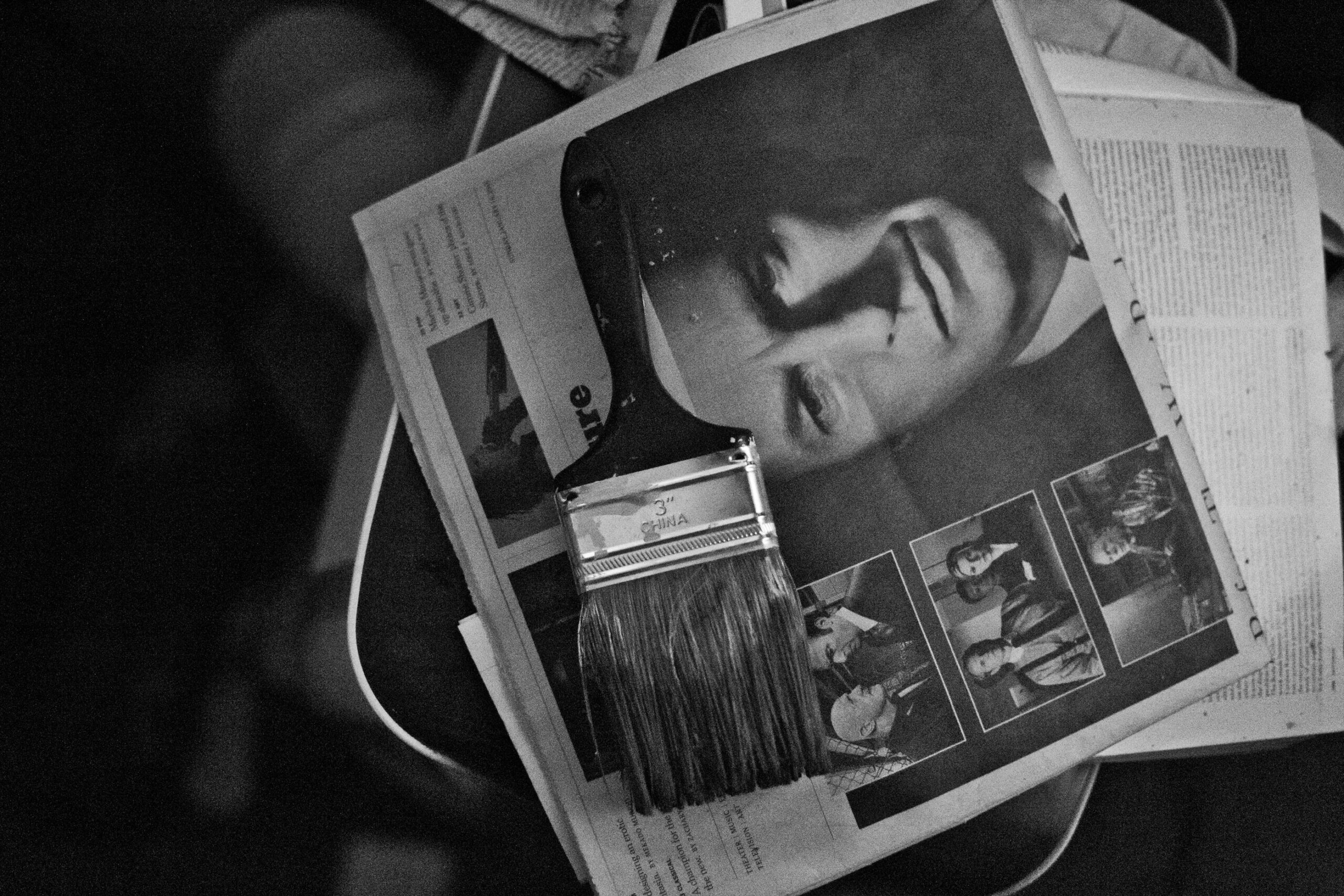

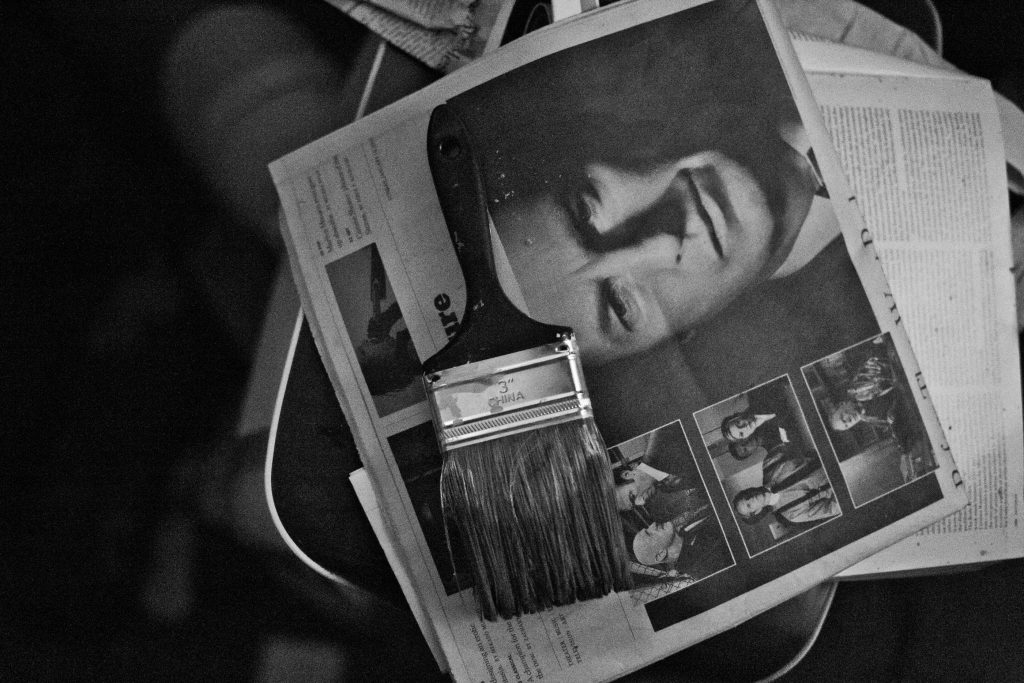

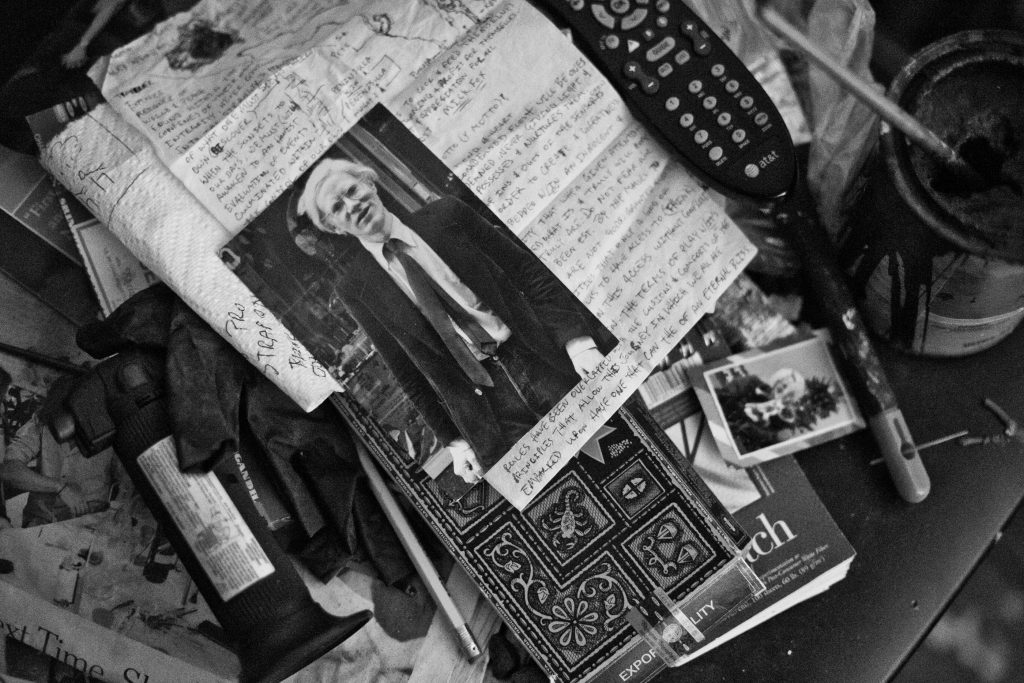

Walking into Stephen’s Germantown studio a couple of hours earlier, I was immediately taken aback by the state of affairs. His small space was cluttered with empty bourbon bottles, yellowed newspapers, crisp suits hanging on a light fixture, and an impressive collection of business cards occupying the seat of the room’s only proper chair.

“Where should I sit?” I asked awkwardly with a laugh. He gestured toward a plastic folding chair propped near the door as he took his seat in front of his latest piece.

“I don’t really think they are portraits,” he says. “When people hear portrait, they think precision. And I’m not going for this precision. I don’t use a grid line on purpose.”

Stephen is a burly but timid thirty-six-year-old who uses graphite and charcoal to create large, engrossing faces on eight-by-four-foot wood panels. He shies away from questions about racial interpretations of his art. He admits that he doesn’t like conflict and says it’s painful if even his worst enemy holds something against him. The only time he curses in our interview, he makes a point to let me know that he is quoting somebody else. In short, he’s as inoffensive as they come.

“When it comes to my voice, I take a lot of things in and don’t put them back out,” he says. “I’m usually the one who apologizes, and I just suck everything in. It’s a heavy load to carry.”

It’s from that silent weight that Stephen finds inspiration for his larger-than-life pieces. The seventh of eight kids raised by religious parents in small-town Waverly, Tennessee, he grew up sketching while his siblings did the talking. In fact, he was so quiet, he was once asked by a classmate on the bus why he didn’t talk more.

“I said, ‘Well, I don’t really think I have anything to say,’” he recounts.

Fast-forward two decades and he has a lot to say, though he doesn’t do the best job expressing himself verbally. His responses to questions are long and detailed, but his words don’t always work together. His train of thought moves rapidly—so quick, in fact, that he only finishes roughly a quarter of the sentences he starts. When he does follow a thought to completion, his voice often trails off into a low murmur that can be difficult to understand.

And yet it all makes sense. Stephen admits that, since childhood, he’s always wished people could just communicate through images. That’s why he became an artist.

“Sometimes you want the world to shut up and hear you scream,” he says. “That’s why I decided I needed to do these big images . . . I think that’s my way of speaking.”

I ask Stephen a simple question: What is it that he is trying to say?

“I was thinking about that last night,” he responds. “I had a feeling you might ask me something like that.”

He answers by pointing to the portraits themselves. On the sides of the wooden frames, he has jotted various phrases, thoughts that come to the surface as he’s working. “There’s beauty in silence,” reads one. “When you cry tears, which one is most important?” he asks on another. On a self-portrait, he has written “The State of Me,” which he says refers to a stage caterpillars experience as they undergo metamorphosis.

“They turn into a liquid format. Their enzymes break down, and then they reemerge as a butterfly,” he explains. “In some ways, it’s like I’m in that state.”

Coming off a difficult year during which he felt “voiceless” for reasons he doesn’t want to publicly discuss, Stephen is readying for new flight. Last fall, Eric Mellencamp from Rocket Tone Records signed on to manage his promotional efforts. He also recently moved into a new gallery downtown called The Elevator, located in the 5th Avenue Art District. He shares the space with fellow artists Ian White and Dana Olson, and the trio have already hosted several events to showcase their work. And on the subject of his work, he’s currently undergoing an artistic evolution that’s seeing him experiment with color for the first time.

After a suggestion from filmmaker Harmony Korine, who until recently had a studio across the hall from Stephen’s own space, he’s been adding color paint to his charcoal and graphite faces. It’s a challenging divergence from the black-and-white rawness he’s used so well to humanize his subjects in the past, but Stephen says it allows him to put more emotion into the pieces.

“I was almost at a blocking stage and kept going back to where I felt safe but really wanted to progress, and that’s when Harmony said, ‘Don’t be afraid to fail,’” he says. “He encouraged me to use color.”

Next to historical greats like Van Gogh, Da Vinci, Pollock, and Basquiat, Stephen credits Korine as a major influence on his work, bringing him up frequently over the course of our interview. It’s near the end of our time together, after repeated mentions of Korine’s name, that I’m suddenly reminded of Benny’s advice from the clip Stephen showed me earlier.

People, parties, work.

During the previous two hours, Stephen has talked about the opportunities he’s had to meet and discuss art with well-known Nashville figures like Jack White, “Little” Jack Lawrence, and Harmony Korine. He’s mentioned the East Nashville hot spots he frequents like FooBAR, 308, and Dino’s. And above all else, he has made sure I understand how much time he spends at the studio.

“I feel compelled to let you know I am awake at this moment,” he says in a text message sent at 3:19 a.m. a few nights later. “I do not sleep.”

Whether he’s knowingly following Benny’s advice or just being overanalyzed by a writer looking for an angle, it’s clearly not fame or riches that he is chasing. Stephen just wants to be heard.

“My art is my means of a voice, my means of making noise in a silent form,” he says. “Whether or not I’ll have significance, I don’t know, and I don’t really care because I’m just going to keep doing it. I have to do it.”

It’s a good thing he does keep doing it. Nashville is listening to him now.