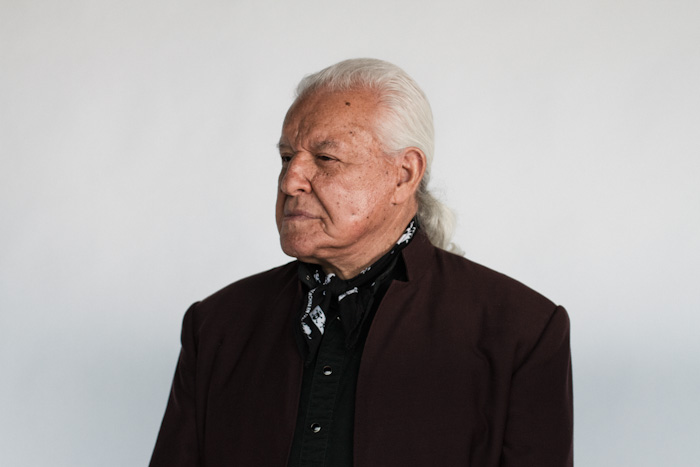

If you don’t know his name, you know his work. Manuel Cuevas—or simply Manuel, as he is more commonly known around Nashville—creates the meticulously embroidered rhinestone suits, jackets, and dresses that line the windows of Manuel American Designs on Broadway.

And if you don’t know his work, you know his clients: Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan, Waylon Jennings, Roy Rogers, Michael Jackson, Elton John, Gram Parsons, Neil Young, and four generations of Williamses—and that’s just the (very) short list.

Over the past fifty years, Manuel has not only helped shape the face of Western wear, but the face of show business as a whole. His name is synonymous with the honky-tonk aesthetic that epitomizes all things country: loud, flamboyant, and, of course, unabashedly American. No one—except perhaps Nudie Cohn, Manuel’s mentor and former father-in-law—has impacted cowboy couture the way Manuel has.

Now, at eighty-one years old, he’s looking to give back to the city he’s dressed since the ’50s. When Manuel isn’t busy cutting, sewing, and designing for current clients like Jack White, he’s working with his nonprofit, the Friends of Manuel Foundation. Through the foundation, he hopes to establish a fashion institute that will teach interns to design and sell clothing in an industrial, mass-production setting.

I found Manuel in the back of his shop with scissors in his hand, signature ascot around his neck, and interns sewing on either side of him. After he gave the interns direction on a black suit (which he continued to do throughout the course of our conversation), we headed to the fitting room to discuss the life, work, and legacy of the Rhinestone Rembrandt.

ON ENTREPRENEURIAL SPIRIT:

My first business was building shoe boxes and filling them up with all of the necessary things. That was when I was like, eight and a half years old. I rented the boxes out and had everybody shoe shining. I was working with wood since the age of seven, and I thought, I could make a nice shoe shine box and rent it out. It started out as a hobby, but it ended up being a good business. I made twenty-five of them, and I’d lease them out totally covered with the stuff—the grease, the potions, the fabric that you need. Apart from being fun, it was really a business.

I think I was making more money than the bank was. I wasn’t going to be a professional shoemaker or boxmaker or shoeshiner, but it was a business. When you have that type of a brain, you just do it and you make money. What’s wrong with that, right?

I had a year and a half of experience doing clothing already in the town where I was growing up—pants and shirts, stuff like that. In fact, I used to make the shirts for the guys that would rent my shoe-shining boxes. I liked that. I knew that if you had a good idea and you put it to practice, you could do just about anything in the world.

ON STARTING IN THE FASHION INDUSTRY:

In this little town of Coalcomán, Mexico, I decided that I was going to make prom dresses because it was a college town. So between weddings and proms, I ended up making seventy-seven dresses the first year. But of course I had this habit of knowing that I can do it, and then I get somebody to do it. So I got about twenty-five more people—little old ladies doing it in their homes . . . I was twelve.

People could have bought Sears-made dresses, but they [the dresses] all looked one way. I could see the grouch on the girls’ faces when they were wearing these. But they were proud when they bought a beautiful princess dress . . . So my idea of innovation got this thing started with all the girls that were graduating. I would charge seventy-five pesos for a dress that would sell in the store for probably fifty [pesos] at the most. So I was super expensive, and it would only take me a couple of hours to make the dress.

So that became an enterprise. We would make three hundred to four hundred dresses a year from that point on. And I never had to sew. But I did the first ones, ya know what I mean?

ON IMMIGRATION:

I came to Baja, California, at the age of nineteen. Then I started a new business: I would provide all the services to people who were immigrating to the United States of America . . . all the documents that you need to walk in there and say, “Give me a damn passport.”

It took forever to get a forma trece—a form thirteen—to come across and just visit and shop in the United States. I said, “I just got an idea. Why don’t we rent an office and we create a net all over the country where we can talk to the local government and get birth certificates, police reports—all the things they [immigrants] need?” What cost us twenty-five pesos, we sold in Baja for $25. So we were making a heck of a business! My partner and me would make a little bit over $2,000 a week.

But I still insisted on making dresses. And I still had ladies sewing dresses, and I was making money.

Then I started looking at magazines like Glamour. I looked at these people, and then I started looking at the prices of the dresses. I said, “You know, I am tired of being rich. I really want to give into myself now. I’m going to impart my own personal human into this.” I’m going to go to the United States of America.

So I went to the bank, put $40,000 in a paper bag, and put it in my brand-new 1950 Cadillac convertible. I crossed the border, got my papers in line. “Welcome to United States of America” was repeated again to me.

ON WORKING WITH SY DEVORE, THE “TAILOR TO THE STARS”:

He was dressing the Rat Pack and all these important people. [When we first met], he was really interested in me, and he looked at my nails—you know, my manicure—and my suit. And he said, “You made that suit?” I said, “Yessir, I make my own suits, my boots, my belts. I make my jewelry.”

He says, “Do you like to drink?” I say, “Of course!” He says, “I want you to do this job for me: I want you to drink with my clients and do fittings. And every fitting that you do, I’m going to pay you $55. I’ll guarantee you three fittings a day . . . I want you to drink and never sound American! I want you to sound foreign!” He was Italiano, you know, hard-core. He wanted me to sound foreign because there were no American tailors.

I played the game, and sure enough, the first person I met was Johnny Weissmuller, who played Tarzan. And then I met Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr., Dean Martin, you name it . . . I didn’t know who the hell Frank Sinatra was. I was a boy of twenty-one, and I was swinging the chicks to Tommy Dorsey and Glenn Miller. This Rat Pack thing had no connection to my life.

That was a lot of money, but it was kind of boring. You know, making tuxedos and fitting straight suits all the time—that’s not really what I wanted to do . . . I quit the Rat Pack ‘cause I was totally bored of making tuxedos. I wasn’t like that. I like to make more [pauses] . . . other types of clothes. So I went on and dressed the horse and rider. And then I ended up doing so many Western movies and Western shows. And then dressing Nashville and rock and rollers. That was just the topping on the cake. I was doing just fine.

ON HIS CELEBRITY CLIENTELE:

It was always about the candor of great people—like Mr. Richard Harris, like Mr. Henry Fonda, like Robert Taylor, Frank Sinatra, Bob Hope, the grand people . . . I could not care less about the fame.

I was really worried about the items that they were getting—I wanted to make them pretty, make them proud of wearing my clothes. That was it. They could be a beggar, a buffoon, a king, a queen, whoever is famous for three weeks on TV or in the news. I dealt with so many people . . . I could go on forever and ever. Not because I want you to mention the names, but because those people made me in a way, so it’s not like I made them. So why should I have a big, big pride about that, you know?

People that think I’m looking for clients—they’re so damn wrong

ON GIVING ARTISTS WHAT THEY NEED:

People that think I’m looking for clients—they’re so damn wrong. I don’t want that. As far as many people know, I’m the only designer known for fighting clients . . .

In plain talk, it’s this: I let them write their own songs; I let them sing their own lyrics. But I sew my own pants and jackets . . . Some of them might say, “I want ‘em blue. I want ‘em tight”—some of them might mention the other guys’ or girls’ clothes. You know, “I want this to be like this.” I say, “No, you’re going to have your own.”

It’s gonna be a real cold day in hell the day that I make you a Johnny Cash suit if you don’t look like Johnny Cash . . . You must have, you must create your own style. I got so many people that wanted to look like Johnny Cash, but they’re in front of the mirror, three hundred pounds, 5’1”. What am I gonna do with that? Gimme a break! That’s not right. But Johnny Cash is iconic, so people want to be like him.

ON DRESSING THE MAN IN BLACK IN BLACK:

He [Johnny Cash] said, “How come my nine suits are black?” And I said, “Well, there was a special on black clothes.”

I think it might have been Barbara Walters or something—she said [to Johnny Cash], “So, Manuel put you in black.” And Johnny said, “Well, I wore black before, but Manuel put me in a better black.” Which was kind of permanent. I was hesitant to admit that I was right until he called me and said, “I want more clothes.” The color was no longer in question.

I knew Johnny Cash very close. Very dear friend, almost a brother. The respect that we generate for each other [trails off] . . . I showed him it was the style. It wasn’t the color black; it was the style.

ON FUTURE PROJECTS:

I want to make a series of classics: suits I have made through the years for people. I’ve never made copies of anything—[but now] I wanna make similar pieces. They cost so much to make, but I don’t mind if anybody buys them. Johnny Cash would be one of them; Lone Ranger would be one of them; Robert Mitchum would be one of them. There’s so many that I want to make serious—it could be a couple hundred of them, honestly. I don’t think anybody will buy them because they’ll be so highly priced. But I kinda want to see them together when I go. I wanna see them. They were meaningful in my life.

Because I was happy when I finished them, I was like . . . I didn’t know I was making clothes for a great man when I made for Hank Williams Sr., Rose Maddox, people like that. I always have regrets that I didn’t grab it.

ON HIS INTERNSHIP PROGRAM AND PROPOSED FASHION FOUNDATION:

A dream is a dream, no matter what size. What I want to do is create designers that can compete with European designers, believe it or not. You know why? The simple reason is that in five-hundred-plus years of this country, America has never produced an international designer. American designers have somehow become designers of name, but never really international designers. You can hear Americans claiming, “Oh, this is Italian, this is French, this is English” . . . I love Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger, I know them personally, but . . . they are not international.

People go and get international designers’ clothes everywhere in the United States of America. They think that is the biggest luxury because they can afford a flight to France or Italy. But that doesn’t make the clothing better. But I think we have some bad clothing in America . . .

Americans, they came from the poor. So when they had a dollar or two, they’d go out and brag all over the world. That’s cool, there’s nothing wrong with that, but let’s not turn it into an American tragedy.

Entrepreneurs are buying clothes from different parts of the world, and they are forgetting their own working class. They make their fortune—and I don’t blame them, oh my God, God bless ‘em—but they sacrifice the little people for that.

I figured if had followed the path of many other people, I’d probably be gone by now

ON AGING AND LESSONS LEARNED:

There have been revealing times of reality lately—you realize you’re mortal; you realize they’re a lot of things that might affect or change you. Not because you want to change, but because of the circumstances.

Now I realize I need to work for a living . . . I’ve been very successful in my life, but the work hasn’t provided enough for the way of life. I call that feo, which is ugly. I really believe in this picture life, and I believe in the good things. Money will never give you happiness, money will never give you love, and money will never give you health. Money is a manipulative object.

I figured if had followed the path of many other people, I’d probably be gone by now. But I never had that kind of stuff—I had my own way of thinking to the point that at one point or another, I recognized that I would be the architect of my own destiny. You know what, you kind of have to manipulate your way in life, and you can really do whatever you want to do.

ON HIS HEALTH:

I’ve never had a hangover in my life. I’ve never had a headache, ever, in my life. I’m just a happy go-around boy.

ON HIS LEGACY:

I want them [people remembering him] to say, “It could never have happened to a better fellow.” No regrets, no nothing. I’m fine. When people become argumentative, this and that, I feel weird about that. I say, you know what, they should have lived a better life. What do I care, really?

I don’t worry, because I want self expression to reign forever, ya know? To give serenity. Because self expression is the greatest thing. Scream if you’re happy, scream if you’re angry. Ya know? Just scream! Because communication is the mother of understanding. If you don’t communicate, nobody knows you’re happy, and nobody understands your pain.

I love what I do; I love the cloth; I live in devotion to what I do. But if fate changed that, I wouldn’t at all be disappointed. I just think that life has its turns, and I am very agreeable to whatever might happen. It’s never been for the money. A lot of people might say well of course [it is], which is fine . . . I decided to stick with what I love to do, and I’ll probably have scissors in my hands the day I croak off because I love it so much. I hope so, ‘cause that’s what I like.

Suggested Content

Chelsea Kaiah James

Why aren't there any ears sculpted onto the presidents of Mt. Rushmore? Because American doesn't know how to listen. - Unkown

Contributor Spotlight: Dylan Reyes

When I create, I often think of what Johannes Itten said, “He who wishes to become a master of color must see, feel, and experience each individual color in its endless combinations with all other colors.”. I’m also inspired frequently by love and loneliness and want folks consuming my work to be encouraged to start paying attention to the little details in everyday life, appreciate the simple things, and let them eventually inspire you! Ultimately, I’m just trying to become a mother fuckin master of color.

Secondhand Sorcery

A look inside the beautifully cheesy world of Crappy Magic