I went out to Craig Carlisle’s farm studio specifically to see his Letters to a Friend paintings. I don’t know how I knew about them, or how I knew I needed to see them in person, but there we were in his bright barn studio on a 19th-century farm south of Nashville, pulling giant paintings out of his storage racks. While they share a gene pool with the work for which Carlisle is known—large heads, fanciful, sprightly demigods—the Letters are distinctly unified and deeply personal.

As a painter, you might try to remember what drew you to painting all those years ago: the smell of paint or the thrill of watching colors mix, the fantasy of make-believe, the satisfaction of realistic portrayal, or the infinite potential of a blank surface before the first mark. Decades into the profession, you may be accustomed to/resigned to/comfortable with (the latter being the least likely) seeing your paintings as a commodity; they are shown, marketed and collected, and it’s an honest living.

Then a friend dies. And when you go back into the studio, something new appears. If our paintings function as communication, and communication changes as our lives change, then new life experiences should cause a shift in our paintings. Such is the case with Letters to a Friend.

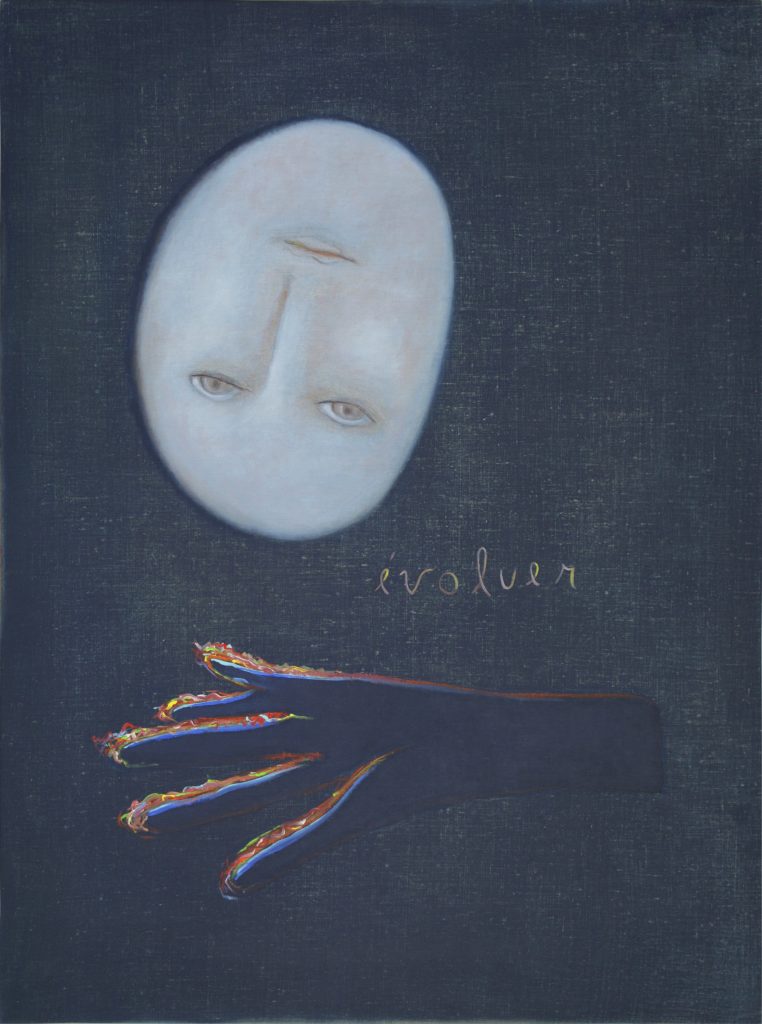

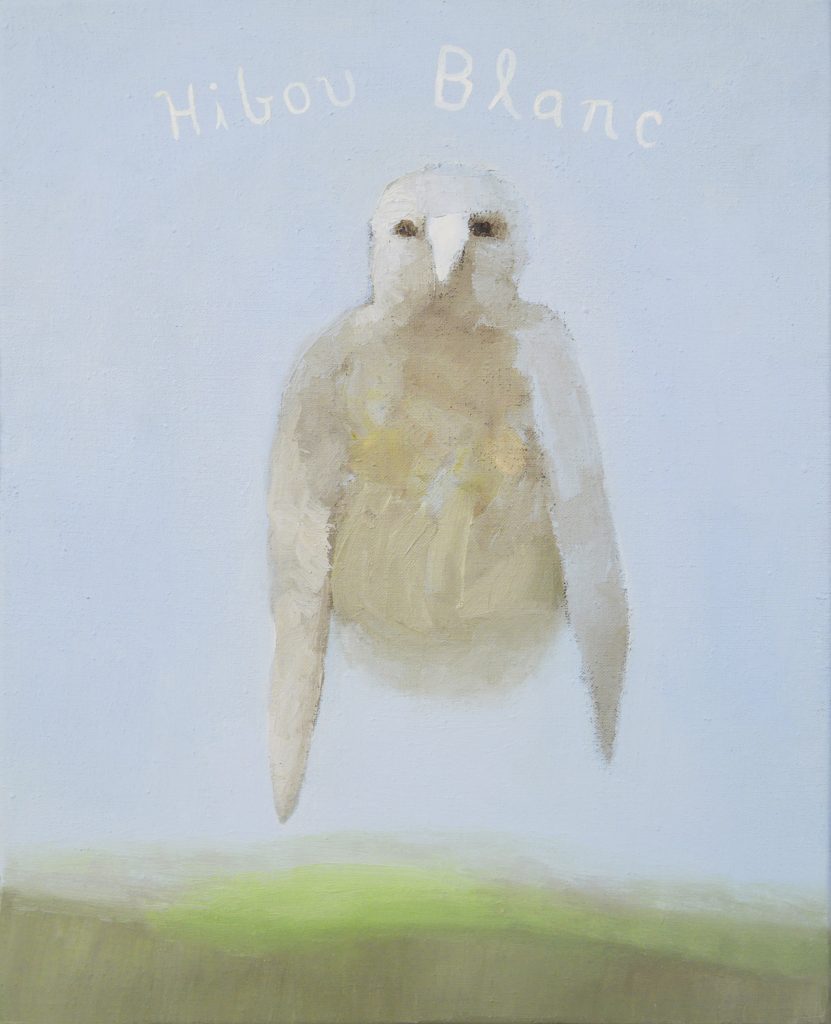

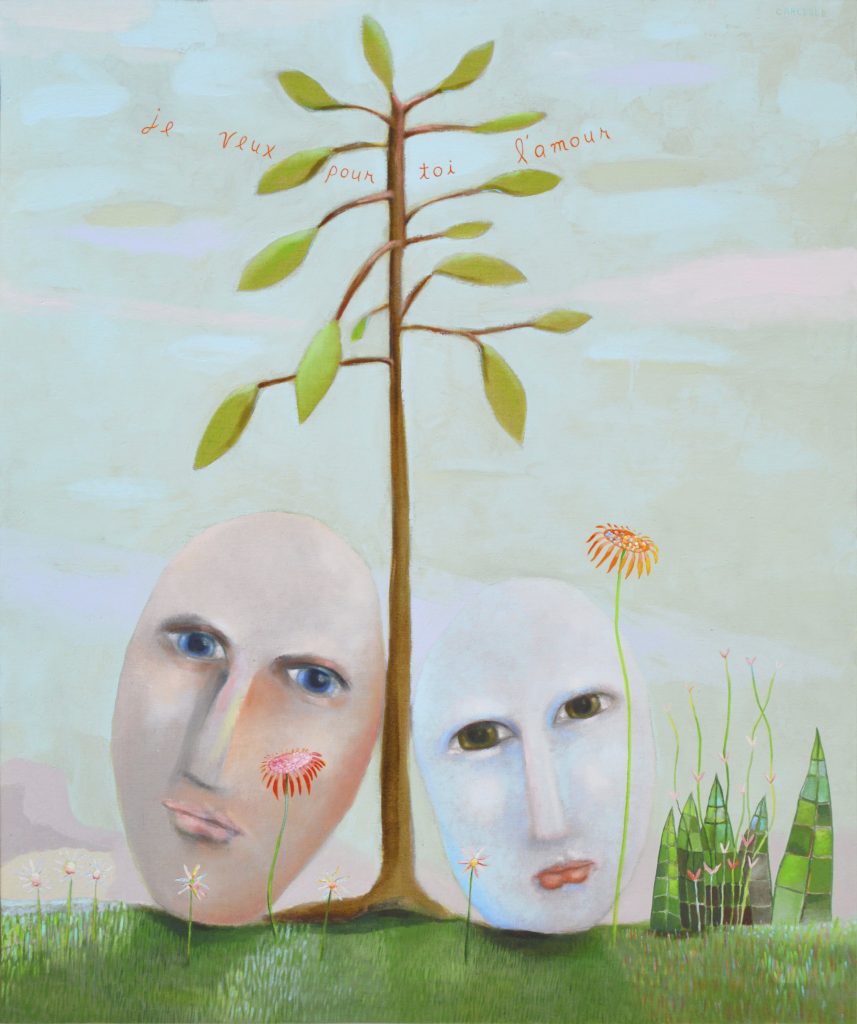

The day he moved into this studio, Carlisle’s best friend of a quarter-century died suddenly. The same day, he began what would become this series. The texts and images in these works might be seen as a call-and-response between Carlisle and his friend, who was devoted to Paris, and wherever he is now, Carlisle says, he is surely speaking French.

Even as these paintings are a response to loss and bereavement, they are colorful and varied, even playful. Some are nocturnal, but most are bright like the morning, suffused with airy text, not dense volumes. There are disembodied limbs—not the horrors of Goya, but hopeful, prayerful arms and legs of Milagros. They are primitive, preverbal signals of humanity. Touch. Intimacy. Above all, they are markers of vulnerability.

It is tempting to try to decode symbolism, to cinch a painting up into a good, single, tangible meaning. But the job of the artist, which Carlisle has taken up fully with this series, is to respond in-kind to life’s inexhaustible and often beautifully unresolvable questions.

—Noah Saterstrom, Guest Curator at Julia Martin Gallery

Letters to a Friend will show in two consecutive monthlong exhibitions at the Julia Martin Gallery from April 6 to May 25.

Suggested Content

Chelsea Kaiah James

Why aren't there any ears sculpted onto the presidents of Mt. Rushmore? Because American doesn't know how to listen. - Unkown

Contributor Spotlight: Dylan Reyes

When I create, I often think of what Johannes Itten said, “He who wishes to become a master of color must see, feel, and experience each individual color in its endless combinations with all other colors.”. I’m also inspired frequently by love and loneliness and want folks consuming my work to be encouraged to start paying attention to the little details in everyday life, appreciate the simple things, and let them eventually inspire you! Ultimately, I’m just trying to become a mother fuckin master of color.

Secondhand Sorcery

A look inside the beautifully cheesy world of Crappy Magic