“It’s important to get your cigar lit right. It’s like starting a relationship out with a good-looking girl. Get it right, don’t mess it up right off the bat . . .You’re doing good, that’s a perfect cut. Alright, look, another thing is, when you light this thing, you burn straight in. Don’t burn sideways. You got it?”

“Yeah, yeah.”

“Okay, and why would you not burn it sideways?”

“Um . . . ‘Cause it won’t burn evenly?”

“Damn, you’re smart!”

This is the sort of candor Barry Walker employs in most conversations. Whether he’s talking about cigars, motorcycles, music, God, real estate, rattlesnakes, life, or death, he’s going to have plenty to say. And he’s going to say it fast. Really fast. He’s also going to say it loud, with interjections of sarcastic, self-deprecating humor and larger-than-life gusto.

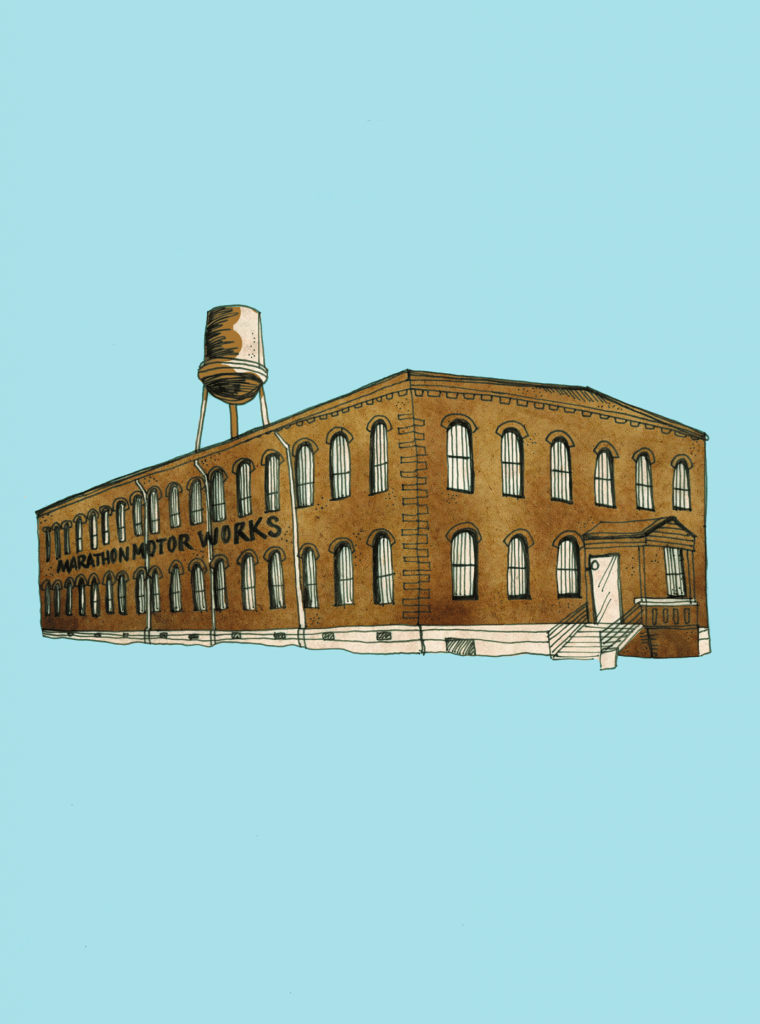

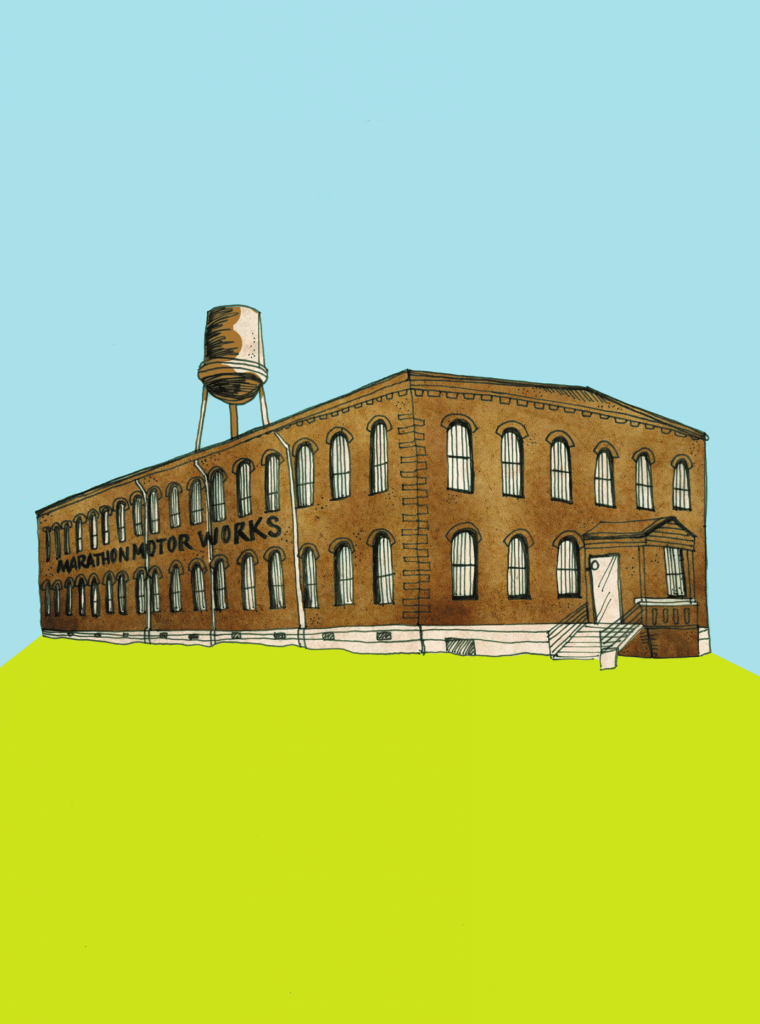

Maybe that’s because he is larger than life. Thirty years ago, at the age of twenty-six, Barry bought the then-abandoned Marathon Motor Works office and administration building. Then, after years of legal battles with real estate “ crooks” (this is one of Barry’s favorite words) and literal battles with the drug dealers, addicts, and murderers that hung around the dilapidated site, Barry bought the MMW factory building in 1994. In the time since, he’s seen the aforementioned murderers kill people, lived through a gruesome motorcycle accident that left him paralyzed, and been declared legally dead for six minutes. He’s also made the Marathon site into a bonafide Nashville staple that attracts tourists looking to see the American Pickers store, locals looking to see shows at Marathon Music Works, and more than a hundred tenants, including Lightning 100 and Corsair Distillery.

For a guy that’s been through some serious shit, Barry is downright jovial as we smoke cigars—he says he buys about eight boxes in a month but gives most of them away—and drink tequila from his homemade dispenser at his office in Marathon. He waxes poetic and spouts life advice; cracks jokes at my expense (to be fair, my cigar knowledge leaves a lot to be desired); and reminisces about a Nashville that’s very different than the one we live in today. Before I can even get out my first question, Barry launches into the first of many, many stories. This one, like most of them, ends on a reflective note.

“Hell, it ain’t about money, it’s what you do in your life! You know what I’m saying?” he exclaims, leaning across his desk from his electric wheelchair. “If you’re on a roll and you enjoy what you do, you can do anything you want if you just put your mind to it.”

It’s an outlook Barry has lived by since his childhood in Jackson, Tennessee. Born to a father who worked for a “consolidated loan and lease” and a mother who worked at the hospital (“they never gave me a dime” ), Barry showed a propensity toward building pretty much anything and everything from an early age. He claims to have built at least three hundred treehouses and forts in Jackson and recalls a childhood spent digging old wagon wheels out of ditches for fun.

“I was born that way, man,” he says. “I just always took charge my whole life. And you know what? I was always funky and creative . . . I had metal shop in high school and learned to weld, so I was always building shit. I was like the kid in this ditch. People say, ‘Where did you get your education?’ In a ditch.”

Well, a ditch and a couple of years at Jackson State and the University of Tennessee studying liberal arts and design. Perhaps predictably, Barry didn’t exactly take to college. “I was too crazy. Too busy building stuff or doing stuff . . . Really, I was terrible in school. I was bored in school. But when it comes to design and engineering and a lot of shit, that just becomes normal for me.”

Nonetheless, it was music—specifically drumming—not design, that brought Barry to Nashville. He’d been playing since the fourth grade, and he remembers his ’80s self as a technical, old-school, “real power drummer” who twirled sticks and spat fire onstage. Upon moving to town, Barry gigged with local “piddly” bands and picked up side jobs wherever he could, including stints at the Country Music Hall of Fame gift shop and the Red Cross. But like college, Barry (again, perhaps predictably) didn’t really jive with the music industry.

“I got tired dealing with—not all of them—but mostly lazy damn musicians,” he says, still looking a little frustrated. “I had three goals in my life: be a rock ‘n’ roll drummer, be a race car driver, because I used to do a lot of racing, or have my own business. I did a little racing, not much, just crossing as a kid, and then drumming and music. I realized [music] was a hard field, and I got tired of all the bullshit and the attitude, so I went into my own business.”

Most people looking to start a business would search for investors or take out a loan. Barry bought a motorcycle. A wrecked, $300 motorcycle (sidenote: Barry has a freakish ability to remember the price of seemingly everything he’s ever bought). He then sold said wrecked motorcycle for a wrecked car. He repaired and repainted the car, selling it for $3,500, which he used to buy a table saw and tools. And just like that, Barry’s first business, The Ingenuity Shop, was born. No investors, no venture capitalists, no stock options—just a guy in his twenties with a table saw and a lot of determination.

The Ingenuity Shop found early success building audiovisual mixing consoles around town, though Barry admits, “I didn’t know what the hell I was doing, but I did good one once, so I did more and more.” Shortly after, the shop secured work at Vanderbilt refurbishing elevators and repairing laminate doors. Again, Barry had never refurbished elevators or repaired laminate doors in his life. Before too long Vandy offered him a contract—a real, $250,000 contract—to help hire skilled laborers for odd jobs around the hospital. Barry was twenty-six.

Needless to say, The Ingenuity Shop had outgrown its humble office on Meridian Street, where rent was $110 a month. The former post office was busting at the seams, and he was sick of meeting clients at restaurants. So naturally, Barry set his sights on a building full of literal shit, toilet paper, dead dogs, and used needles.

“I saw this building, and I was just taken by it. I had my eyes open and said, ‘My God, that’s beautiful!’ This building, vines all over it. I drove by it for a year and a half, and I said, ‘I’m going to see what it costs to buy that thing.’ I checked into it and bought it from an investment company owned by a bunch of crooks.”

Thirty-two thousand dollars and a few straightened-out crooks later, the MMW administration building was Barry’s. Restoring Marathon would consume the better part of Barry’s life, and like almost everything he sets his mind to, it wouldn’t be easy. In 1986, the area we now call Marathon Village wasn’t crawling with hip young professionals and American Pickers–seeking tourists. Barry, who’d converted the third floor of the building into an apartment, was actually the only legal resident on-site at the time.

“There were more murders, more people killed in Joe Johnson than [anywhere in Nashville]. I have to tell you that’s how bad it was,” Barry says, shaking his head. “ I’ve dealt with it all, man. I’ve dealt with people shooting at me, people threatening to kill me, seeing people die, finding dead bodies, people getting the hell beat out of them.”

As is the case with all things Barry-related, stories abound when he discusses this time in Marathon’s history. He laughs at some—like the time he pranked a group of squatters by convincing them the place was infested with rattlesnakes.

I’ve dealt with people shooting at me, people threatening to kill me, seeing people die, finding dead bodies, people getting the hell beat out of them.

Others haunt him to this day. There was the woman he found by I-40 with her throat cut open. The eighteen-year-old-boy who bled out after being shot during a drug deal. The “God-awful” screams he heard while working in his shop one day—screams that led him to find a grown man beating a six-year-old girl within an inch of her life.

“Her mouth was bleeding, her nose was running, she was screaming, and people weren’t doing anything,” he recalls. “I came up behind him, and I put my damn .38 up to his head and said, ‘You hit her again, you’ re dead.’”

By 1994, Barry had acquired the rest of the site—namely, the 130,000-square-foot MMW factory—for $350,000. In the eight years between ’86 and ’94, he never stopped (and still never stops) making renovations. He relied heavily on repurposed materials: Glass from a demolished Red Cross building became windows. Furniture and marble from the Brooklyn Center in Minnesota went into bathrooms and kitchens.

“If you don’t have money, you got to make things happen,” Barry says. “There is so much waste in this country, you can build anything. There’s so much stuff.”

Pretty soon, people noticed that the old, run-down car factory off Charlotte wasn’t so run-down anymore. Before he knew it, Barry had a few tenants, and people were even asking him to throw events at the space. Perhaps most notably, he inadvertently hosted a series of ecstasy-fueled raves (video evidence of which still exists in dark corners of the Internet) throughout the ’90s.

When asked about the raves, Barry explains, “I walked around in the early days, but I couldn’t handle the music, so I walked out. I had to leave. I thought, Okay, these kids are going to listen to music—amped up weird music. But I didn’t realize [anything was wrong] until a cop appeared saying they were ready to shut the place down. I said, ‘Why?’ They said, ‘Hell, it’s just a drug fest!’ I said, ‘What?!’”

Violence, raves, and drugs aside, Marathon continued to flourish well into the new millennium. But Barry’s life was about to drastically change. In 2008, Barry was in the midst of a divorce, so he did what a lot of middle-aged men do in the midst of a divorce: he bought a brand-new Harley. This wasn’t anything foreign for Barry, considering he’d bought and sold—though not necessarily been on—motorcycles for the past twenty years.

So when he and his buddies planned a trip to visit Corky Coker (of Coker Tires) down in Chattanooga, no one thought twice about it. They even took the scenic route home, opting to go through Signal Mountain via Suck Creek Road instead of the interstate. But then, out of nowhere, Barry realized he was in trouble.

“I was going around a curve doing about fifty miles an hour, and a rock or deer or something jumped in my way . . . and I saw a car coming,” he says, speaking as nonchalantly as he does when talking cigars or vintage Marathon cars. “ I could’ve slammed on my brakes, which I probably should have done, but I thought, Okay, I think I got enough time to miss this car and I’ll just run off to the trees so they don’t kill me . . . But then the car, instead of going straight, it curved over to miss me, and I curved and I hit it head-on, man. I saw the light.”

Barry’s body broke the car’s windshield, and he was jettisoned seventy feet down the road into a cluster of boulders. The next thing he remembers is a woman from the nearby mining company—who just happened to be a nurse—standing over him and repeatedly asking, “Are you okay?” He most definitely was not: Barry had torn his pelvis in half, sliced multiple veins, broken all of his ribs, shattered his leg, and effectively lost his backbone from his waist to his shoulders.

Though he laid in the road in shock and totally paralyzed, he still managed to ask for two things: 1) For someone to get his daughter and his estranged wife on the phone. “I thought, Well, if I’m going to die, I’m going to sit here and I want to talk to them before I die.” 2) For someone to move the weeds out of his face. “They were driving me crazy!” he laughs.

According to the nurse, Barry was dead for about six minutes before someone—not a paramedic, mind you, just some guy passing through Suck Creek Road—fortuitously came by with a defibrillator. If he hadn’ t passed by the wreck, I probably wouldn’ t be talking to Barry now.

“I just remember coming out, looking down on the whole damn wreck site, man,” Barry explains before starting to laugh. “Unless I was hallucinating, I don’t know! Then I remember I saw this little crooked door about four feet tall, and it had this real bright light around it. I kept going towards the door and then something said to me, ‘That door’s not right, don’t go to the door.’”

Barry would die two more times as he was life-flighted to Erlanger in Chattanooga. While there, he caught pneumonia, staph, and MRSA, and he even received his last prayers multiple times. After about three months, he was moved—he came close to dying again in transit—to the ICU unit at Shepherd in Atlanta. Soon after, he started the grueling process of physical therapy.

Rehab, though, was nothing compared to accepting the limitations that came with being quadriplegic.

“My personality is building and welding and all the shit I always did,” Barry remembers. “Now I’m paralyzed. It was a hard thing. The first eight or nine months, I drank a lot and stayed drunk a lot . . . I just couldn’t believe it. Everybody thought I’d kill myself . . . I said, ‘You know, I’ve been through everything in the world: starting my business, fighting codes, dealing with people getting killed, shooting at people, getting shot at, everything. And here I am, paralyzed.’

But what it did for me at Marathon is kept me more focused on my projects.”

That’s an understatement. By 2011, Barry would not only renovate another thirty thousand square feet, but he’d also bring in his two biggest tenants: Marathon Music Works and American Pickers. The Pickers store, particularly, transformed Marathon Village into a Nashville destination (Barry jokingly complains that it also shot Marathon’s water bill up by 800 percent).

Now, on top of tenants wanting to get in—there’s a perpetual waiting list and Barry turns down anyone who isn’t doing something creative—companies are constantly gunning to buy the whole site. A $20 million offer here. Thirty million there. Barry isn’t going anywhere.

“[Companies] said, ‘Just think, you can build a big house.’ I said, ‘Yeah, I can do that now,’” he laughs. “I mean, a man only needs so much money. Anything else is just waste.”

And if there’s anything Barry hates, it’s waste. He’s currently in the midst of renovating the few undeveloped areas of Marathon—there’ s a movie theatre planned that’ll show films about the history of Marathon, but he’s more excited about a bar tentatively called Gearheads.

“Everything is going to be mechanical,” he explains. “I bought an 1899 hit-and-miss engine, it’s going over the bar. A lot of mechanical things, we’ll have cars hanging over, all pre-1918.”

He’s also working on multiple “historical urban renewal” projects in Jackson, which is not only his hometown, but also the hometown of Marathon Motor Works (he discovered this after he found some old photos in an abandoned house years ago). And as was the case with Marathon, Jackson presents new obstacles, new opportunities for ingenuity, and, of course, new crooks.

“You’ve got to be able to have a vision and carry that vision until it becomes reality,” Barry says. “People quit. People get injured, they get crippled, most people give up . . . It’s all about what you create, and it’s basically you creating your own reality.”

The vision expands, the reality remains intact, and Barry Walker lives to fight and create another day.

MORE INFO:

BARRY WALKER

marathonvillage.com

Follow on Facebook @MarathonVillage

Suggested Content

Chelsea Kaiah James

Why aren't there any ears sculpted onto the presidents of Mt. Rushmore? Because American doesn't know how to listen. - Unkown