Paul Collins is a local artist and professor at Austin Peay. He has an MFA from Yale; he’s been a resident at Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture, Anderson Ranch Arts Center, and the Vermont Studio Center; and his work has been featured in New American Paintings, Fresh Paint, and Artvoices. For his new exhibit, Fortnight Sessions, Collins left the confines of his studio and painted eight locations around the world. Every month, he spent two weeks on-site chronicling everything from The Colosseum in Rome to a neon PBR sign at Grimey’s to election signs in North Alabama. The result blurs the line between journalism and impressionism and forces the viewer to rethink (or maybe just think about) the way we interact with the spaces around us. Read our conversation with Collins below, and check out Fortnight Sessions, showing now through March 31.

You’ve been a studio artist for thirty years. What challenges emerged as you created art in public spaces for the first time?

In no order: weather, my capacity for social interaction, working against the clock, and trying to capture life in motion.

By creating live art in public places—particularly places where one wouldn’t expect art to be created—did you feel like you were making a political statement? Or did you see yourself more as a journalist reporting the events that unfolded before you?

Both. I do want to be seen working to show the world that art is work and that making pictures is important. To your second question, I have thought of this process as journalistic, and that’s new to me. Maybe a slow journalism, maybe a could-be-drawn-better journalism, but still a witness story in the same way journalism brings experience to others. Even while drawing frozen brassicas at Rocky Glade Farm, I felt like: “Why haven’t I seen this before? People need to see this.”

What drew you to the locations you captured for Fortnight? And during the process, did you find any similarities between these seemingly disparate communities?

One thing has led to another. My first public project was a mural for the side of Alex Lockwood’s Elephant Gallery building last spring. A month later I was teaching in Rome, and it was that mural experience that got me painting on the street. Back in Tennessee I was showing the drawings to Anna Zeitlin of Zeitgeist Gallery and out of my mouth popped, “Now I want to draw Nashville and be a tourist in my own town.” It started that simply. But almost as soon as I began, I knew that these locations could line up to make a broader portrait of our world from different angles. Every time I start a drawing, regardless of location, I am working to frame the rich interplay of the human and the natural, of control structures and uncontrollable change. I’m hoping that capturing that dynamic will reveal our likeness.

Step back and let me explain how badly the Trump election scrambled my eggs. It has challenged me to seek reality where my past work has celebrated imagination, rumination, and play. It has made me want to look specifically at society’s institutions and methods directly in a way I have not in past work. I try to let big questions lead me to a site where I then reside and meditate through pictures. Big questions like: Where does food come from? What does justice look like? What does democracy look like?

Another big question that art always asks is Why do things always disappear? Some ubiquitous things will simply not be here in a few years—you can’t not have perspective when drawing a phone booth at a gas station. I started to draw Fort Negley because I expected it to be screwed up by development, and I put Grimey’s on the list when I saw the “For Sale” sign on the building.

Fort Negley is one of the locations prominently featured in Fortnight. Did you decide to draw it before or after the whole debate surrounding the Fort started? And, by drawing the Fort as it currently is, were you in some way reacting to proposed plans for turning it into this hip, urban, creative hub?

I knew the site was richly and historically complicated, but I did not know about the debate when I decided to work there. I heard about the development plan on my first day there from the ranger. I was pissed. I thought cynically that it was a done deal and that Nashville’s unstoppable building orgy is just a sign of the times. I wrote a letter to the mayor and Parks Department and whoever and asked if we could just keep maybe this one thing for the next generation to develop. Just one? Fort Negley is a gem. Go visit. Seriously. Restoring the natural space under the derelict stadium and parking lot will enhance the city for generations in a way that even an Amazon headquarters couldn’t. I had the privilege of showing the drawings I made at their visitor center for the month of October. One of my drawings is of St. Cloud Hill’s sister, Edgehill, as seen through Negley’s Osage trees. It’s covered by a seamless carpet of buildings. I hope the comparison is obvious.

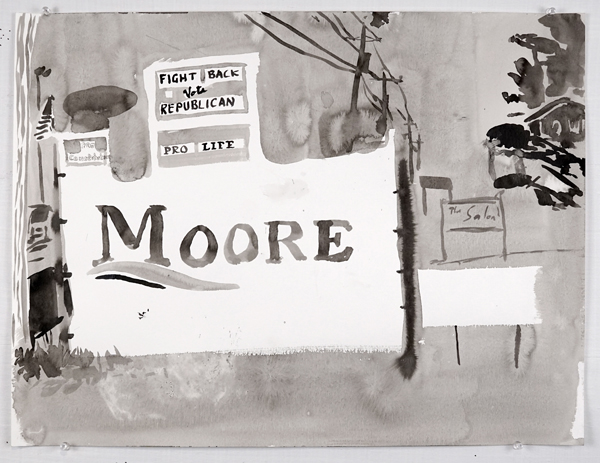

Tell us about traveling down to Alabama and drawing during the Moore/Jones race. At what point in the campaign did you decide to go down, and what were your takeaways from covering such a divisive—and maybe even surreal—event?

It occured to me on Sunday that I could just drive to Alabama for fourteen hours on Tuesday and draw an election. Well, hell . . . So I went. I felt like it would be the perfect test for this new modus that sprang from last year’s election to visit the most Trumpian election event of Doug Jones vs. Roy T. Moore. I have to admit I pretty much failed the test, but I’m calling it a productive failure. First off, the drawings are really boring—just scenes from polling stations and different roadside signs. I lost a ton of time chasing stories—like Roy on a horse! When I got to Gadsden there was nothing going on. I somehow didn’t think that both driving and drawing would be tiring, and I got home just exhausted. I did eat a fried hamburger and that was new. I also came back with some pictures in my head, and I drew those in the next few days. Those are the only pictures not made through direct sight, but they’re mine nonetheless. Every project teaches me something and tweaks my methods. Again, I met incredible people telling me incredible stories. I did have a few very intense conversations about my purpose there, and in the end I felt like it wasn’t my election to draw. I really hope to be geared up for Tennessee races this fall.

About the public method behind Fortnight, you’ve said, “I was drawn to this method by the goal of increasing my own understanding of my surrounding community and that community’s understanding of art through my own discernible labor, openness, and strength of interpretations.” Did the project succeed in illuminating aspects of these communities?

My writing sounds really pretentious there, but yes. Certainly I have had my eyes opened by what I’ve seen dropping into someone else’s situation. That process seems guaranteed to humble, inspire, and excite me as an artist. I have met just the best people and have gotten wisdom and humor and lessons from all of them. I believe it’s in the pictures I’ve made and better told there than here. As for affecting these communities, I’ll just say that I hope I have made an impression. When I set up to paint it draws people in and we talk, and if they agree to be in the picture, I’ll make two and they get one to take. That’s transactional, but it’s also a gift and a viral message. I hope it has the ability to remind them of what happened when they hang it on their wall or give it to their mom.

Because the pieces in Fortnight chronicled places and events in real time, you obviously had to be hyper-aware of your surroundings and in the moment. Would you say that approach was a reaction to how we often aren’t in the moment because of technology and social media?

Great question, and yes. My devices and digital habits are the hand-forged bars of my personally insulated bubbledom. It’s a problem. I’ve got two amazing preteen kids, and I am scared shitless for the barren digital socialscape that awaits them. That said, I draw on a friggin’ iPad. It’s amazing! I’m not a Luddite. There’s no going back, only forward.

Do you think you’ll go back to the studio for your next project?

My immediate plans are to continue like this for a while. I’m excited to accrue a diverse range of subjects and publish them on an ongoing monthly basis. In the process, I’d like to expand the scope of the projects. Right now—by choice and constraint—I am working locally, but I’d love a challenge like trying to draw Congress at work or spending a month documenting freight going down the Mississippi. I have no idea what I could bring to those pictures that could make a new sense, but I’m excited about the challenge of bringing form to abstraction through direct experience. I am also still so bothered by my ignorance of the world, so I expect that there’s a lot of work ahead for me. I have imagined that I might map the world by targeting blind spots, sort of how Studs Terkel’s incredible book Working surveys the world of employment.

Fortnight Sessions is showing now through March 31 at Zeitgeist Gallery.

Suggested Content

Chelsea Kaiah James

Why aren't there any ears sculpted onto the presidents of Mt. Rushmore? Because American doesn't know how to listen. - Unkown

Contributor Spotlight: Dylan Reyes

When I create, I often think of what Johannes Itten said, “He who wishes to become a master of color must see, feel, and experience each individual color in its endless combinations with all other colors.”. I’m also inspired frequently by love and loneliness and want folks consuming my work to be encouraged to start paying attention to the little details in everyday life, appreciate the simple things, and let them eventually inspire you! Ultimately, I’m just trying to become a mother fuckin master of color.

Secondhand Sorcery

A look inside the beautifully cheesy world of Crappy Magic