“NASHVILLE IS A FIVE-YEAR TOWN.”

That’s something I heard a lot during my first month here. The sentence was always delivered by a musician—some borderline-burnt-out songwriter who’d been playing gigs at The 5 Spot and making friends with the DJs at Lightning 100 long before I came along. Looking back, I understand why guys like that felt the need to put me in my place. I’d barely been in town for five weeks, much less five years, yet there I was, sitting at some bar in East Nashville, ordering the first Yazoo pint of my entire life and telling some longtime Nashvillian on the barstool beside me that I was hoping to land a contract with Thirty Tigers. God bless all the strangers who didn’t laugh in my face. Telling me that Nashville was a five-year town was their way of politely saying, “Man, just wait your turn like the rest of us. You haven’t even begun to pay your dues.”

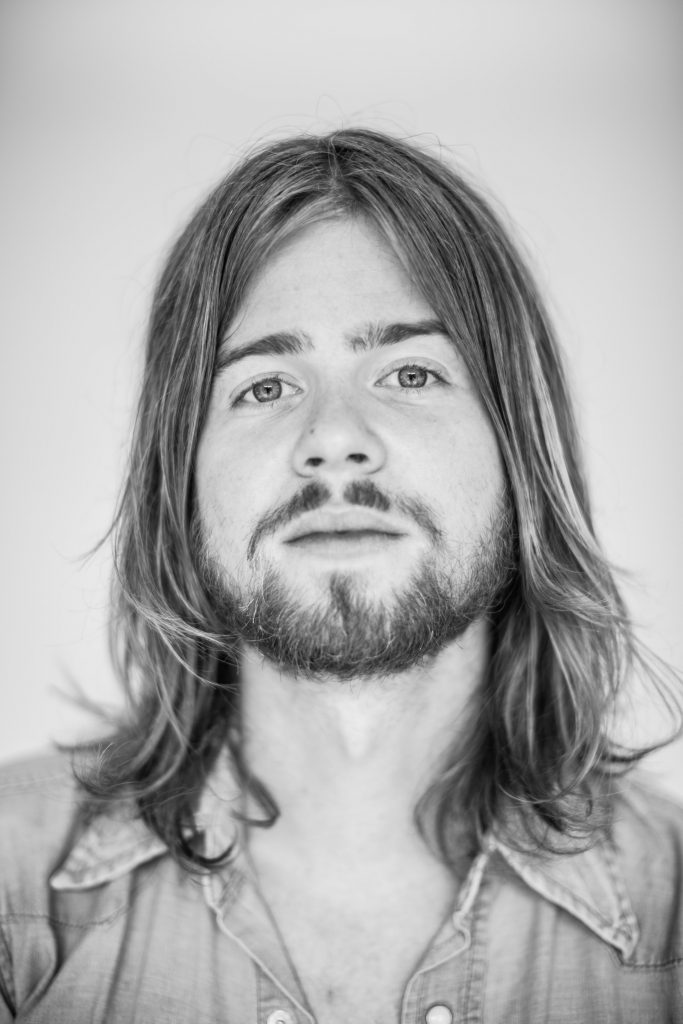

They were right. It took me half a decade—as well as several hundred gigs, a brain operation that left me in recovery for the better part of a year, two independent albums, and a lot of dumb luckto land that deal with Thirty Tigers. This summer, when I release my new album, Skyline in Central Time, on August 5, it’ll hit stores just a few weeks before my five-year Nashville anniversary. The whole thing is making me super nostalgic, which may be why NATIVE asked me to write an autobiographical piece about my time in town. So, in case you were wondering, that’s why you’re reading an article about Andrew Leahey, written by Andrew Leahey.

I write about musicians a lot. When I moved to Nashville in August 2011, I’d already spent the first part of my twenties working as a music journalist in New York City and Ann Arbor, Michigan. I really loved that job—I still do— but I had a hard time reconciling the fact that people like me were getting paid to sit in cubicles and judge other people’s art without having the balls to make art ourselves. Why were we the ones getting health insurance, while these songwriters—the guys I was spending eight hours a day critiquing—were busting their asses on the road and fighting the good fight?

road and fighting the good fight? Music journalism was originally my backup plan. It was an alternate career path that I cooked up in high school in an attempt to pacify my parents whenever they became worried about their son fumbling through adulthood as a broke musician. By the time I hit college, though, Plan A—which was playing music, not writing about it—seemed to be shaping up nicely. I was gigging every week, playing four-hour marathon shows in bars and frat houses while paying my rent as a pit musician for a theater company. It wasn’t glamorous work, but I loved it. And then, when graduation hit and I realized just how poor I had become as an undergrad, I put my own music on hold and moved to Manhattan to take a position at SPIN magazine. Plan B temporarily took over.

To be fair, working at SPIN was awesome. I was twenty-two years old, living in New York, and spending time with people like Ric Ocasek, who came into the office one day to perform some old Cars songs in the company conference room. I met my wife, Emily, at a music conference in Lincoln Center. I sent a fax to Bill freakin’ Murray. The entire experience hooked me. I wound up working for more than a half-dozen other companies during the years that followed before I had an internal What the hell am I doing with my life?! conversation and starting writing songs again. I quit my day job a few months later, and Emily and I moved to Nashville.

Launching a music career is a lot like launching a journalism career. You start off by never getting paid. You accept any gig you can find. You network your ass off. You inch your way toward a place where better gigs and better pay grades await, and eventually, you arrive at that sweet spot where you don’t have to spend all your time looking for work, because work starts finding you. Talent is important, but it isn’t the only thing you need to bring to the table. You need patience. You need connections. And, as Thirty Tigers CEO David Macias told me during our first meeting together, you need a story

For years, I thought my story was going to be a simple one: guy moves to Nashville, forms a band called Andrew Leahey & the Homestead, plays roughly one hundred shows per year and gets his big break. When my band wrapped up a big summer tour in 2013, though, that story took a turn. I was spending an afternoon in Centennial Park with Emily when the hearing in my right ear dropped by 50 percent. I remember that feeling. It happened all at once: a burst of electronic noise (which, I was later told, was the sound of my nerve endings dying), followed by the sudden sensation of my ear being stuffed with cotton and taped shut. My balance and depth perception started to slip too. We went bowling later that night, and I kept accidentally walking into chairs like a drunk person. The doctors didn’t know what to do with me. They tried everything—including shooting a syringe full of steroids through my eardrum and into my inner ear, hoping to blast out the infection—and only agreed to give me an MRI after I passed out in a Kroger parking lot one afternoon, splitting my chin open on the pavement. When the MRI results came back, they were devastating: I had a brain tumor on my right hearing nerve. It was growing—the hearing loss must’ve been caused by the tumor passing some sort of size threshold—and it needed to be removed.

“You’re having brain surgery? Like, brain surgery brain surgery?” That’s how my friend Warren Givens responded to the news. Most of my friends had similar reactions. I was a pretty healthy dude—no meat, no coffee, no nicotine, very little liquor. And I was young. Still, none of that changed the fact that Emily and I suddenly found ourselves taking a lot of trips to Vanderbilt Hospital, talking with a team of neurosurgeons and otolaryngologists about my head.

The doctors were honest with me. They explained that any brain operation carries with it intense risks. I had a fifty-fifty chance of waking up from the surgery with complete hearing loss in my right ear, which would’ve meant the death of my music career. They also gave me odds on whether or not I’d even wake up at all, which would’ve meant the death of me. The twelve-hour operation occurred three months later, in November.

I realized that music—playing to it, listening to it, writing about it, living it—isn't a right or a guarantee. It's a privilege. A blessing.

It was successful, although I’ll spare you the gory details. No, I wasn’t awake, and yes, it did hurt once I woke up. And it kept hurting, whether I was sitting on a La-ZBoy in a hydrocodone haze (which I did for the first ten weeks of recovery—a period that, I should add, would’ve been much worse if it hadn’t been for my wife, who was just beyond awesome throughout the whole ordeal) or taking the Homestead back on the road for another tour less than three months after leaving the hospital. Immediately following that tour—which I booked against the advice of pretty much everyone I knew, simply because I wanted to prove to the world that my career wasn’t over—I came back home and paid dearly for not allowing my body the time it needed to fully heal. My head throbbed. I suffered daily migraines for about four months straight.

I didn’t play one hundred gigs that year. My skull couldn’t take it. Instead, I stayed home and wrote songs. It felt different this time. I realized I’d been taking music for granted during the years leading up to my operation, simply because it was something that had always been around. It was playing inside every car I stepped into. Every movie I watched. Every speaker in every bar I ever visited. After it was nearly taken away from me, I realized that music— playing it, listening to it, writing about it, living it—isn’t a right or a guarantee. It’s a privilege. A blessing. And, for me and thousands of other people in this five-year town, a total necessity.

I wound up taking those new songs, along with a few I’d written b e f o r e I got sick, and recording them in Ken Coomer’s East Nashville studio. The result is Skyline in Central Time. I’ve been describing it as “an album about what it feels like to be alive,” and if that sounds a bit lofty and Bono-ish, so be it. The whole surgery experience woke me up. It made me a better guy, a better musician, a better husband. I never want to go through something like that again, but there are some lessons you can only learn when you’re nose to nose with your own mortality, and I’m doing my best to put those lessons to good use.

A lot has happened in the past half decade—more than any eleven-track album or sixteen-hundred-word article can encapsulate. I think I’ve reached the end of the beginning. To all Nashvillians who’re new to town and just starting their own journey: welcome and good luck. To those who’ve been here awhile—and, like all of us, are still paying those never-ending dues—remember that we’re in this thing together. Let’s all see what the next five years have in store.

Suggested Content

Chelsea Kaiah James

Why aren't there any ears sculpted onto the presidents of Mt. Rushmore? Because American doesn't know how to listen. - Unkown