SEEING THE ART IN TRASH is not always easy for the adult mind. I can only vaguely recall a time when I would anxiously wait for the rolls of wrapping paper at Christmastime to be completely used up so I could ask for the long cardboard cylinder that was trash to everyone else. As a child, I saw endless possibilities in it—it could be a huge spyglass or a sword or a peg leg. As an adult with a slightly dulled imagination and a fear of becoming a hoarder, it becomes harder to hang on to trash. But here at Turnip Green Creative Reuse, they hold on to the belief that imagination is key to reducing waste.

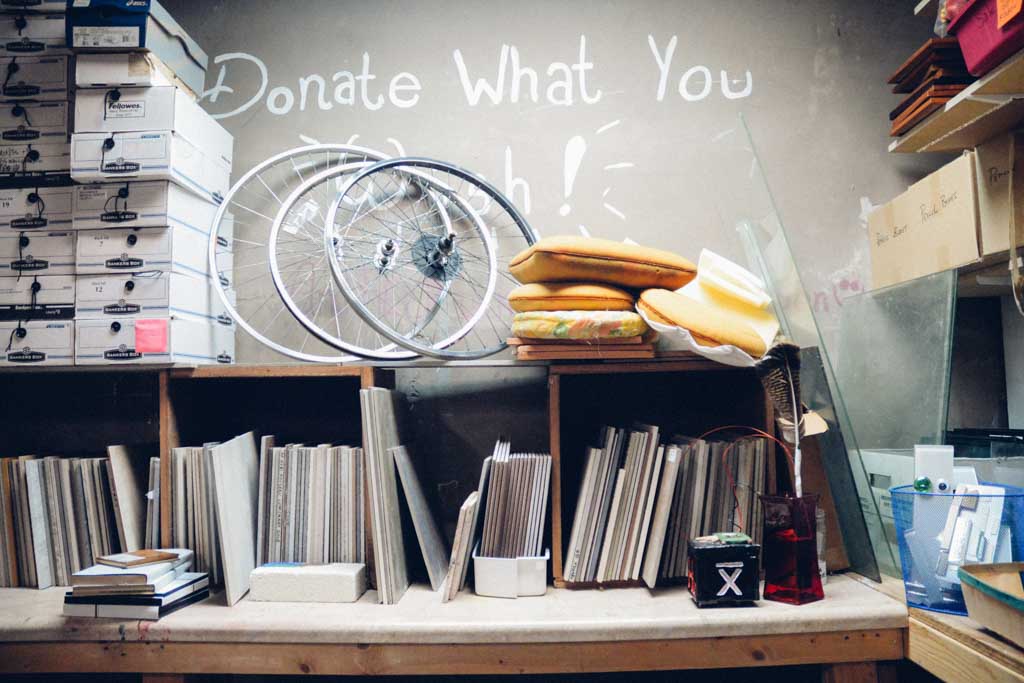

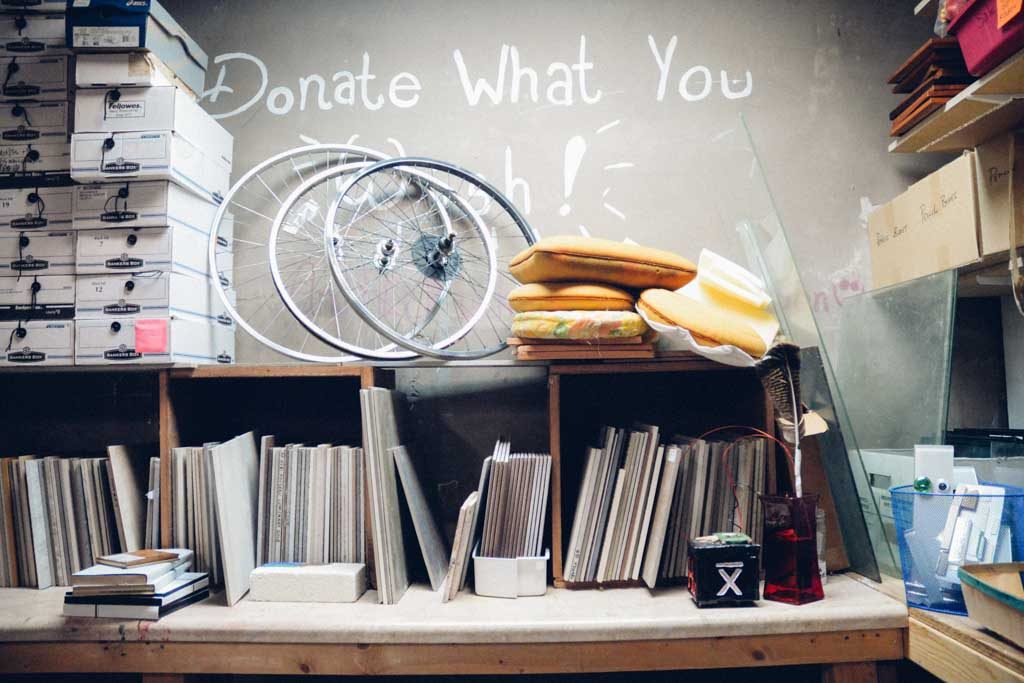

As you walk through the retail space of Turnip Green, you might find boxes of textile samples, vintage fabrics, reused canvases, canvas frames, small figurines, googly eyes, beads, pipe cleaners, popsicle sticks, sheet music, photographs, CDs, stickers, wallpaper samples, carpet samples, frame pieces, stained glass pieces, leftover house paints, spray paints, and the wax from burnt-down candles. In the front section of the building, you’ll find an art gallery displaying works from artists that use recycled and reused materials in their work.

Kelly Tipler is the founder and president of Turnip Green Creative Reuse. Before starting Turnip Green, she worked in nonprofits for more than twenty years. “I had left a social work nonprofit career and wanted to do something more creative,” she explains. “So I got together with some other like-minded, sustainable-minded friends who have businesses that are green or have extensive experience in nonprofit work, and we started doing research on this. Originally I just wanted to work with artists that did reuse work and try to help them with promotion and marketing and maybe an online gallery. And as I started researching [that], I found out about creative reuse centers, and then it just clicked with me.”

The first creative reuse centers started about twenty-five years ago. Turnip Green has been in existence in Nashville for about five years. “We started going to other creative reuse centers to take notes on what worked and what we could bring back and put into a plan for Nashville,” Kelly continues. “We went to North Carolina, we went to California, and we went to New York. We brought everything back we learned in those creative reuse centers and created a plan that looks very much like what we have here. We took the parts we loved from each of those places and melded them together. But we originally just started by doing free workshops in libraries and giving away materials that we had donated and we kept in a shed. Everybody was working out of the trunks of their cars.”

Eventually, Turnip Green outgrew the shed. “We were poor, and we had a drive and a mission, and we made it work,” Kelly says. “We just had the idea that if you keep doing the right thing and it’s creative and good for the earth, then good things will happen. And we are now self-sustaining.”

When they originally started working as a nonprofit, they partnered up with artists’ group Untitled Nashville, who was their fiscal sponsor. Through a networking group, they came in contact with a Platetone Printmaking member and found out they were looking for a building mate. The printmaking co-op is now Turnip Green’s building mate and professional partner. Every third Thursday, they host a free public event. Platetone does an open studio activity, Turnip Green has a gallery show, the shop is open, and everyone pitches in to provide food and drinks.

The Turnip Green shop works through a pay-what-you-can donation system. Nothing in the store is priced. “The only thing that’s priced in our entire building is the art that’s locally made with reused material. Everything else in the place is available to be taken, and we ask if it’s a possibility for whoever takes it that they leave us a donation that they feel is fair or that they can afford. We’ve had people come in and take a few things and give us a hundred dollars, and we’ve had people who will come in and take things and not be able to give us anything. Our goal is to make sure that materials are available to creative people and that all people have access to them regardless of their ability to pay.”

Their material donations (the actual items in the store) come from businesses, design companies, schools, artists, and community members. Anyone can bring in materials as long as the materials are clean and have not had food in them. “However, we do encourage people to not bring clothing in because we feel like it has one more life before us,” Kelly says. “We feel like if there’s a pair of jeans and somebody else could use those, they should use [them] one more time before we just use the denim off of them.”

They keep a tally of the weight of donated items so that by the end of the year they know how much waste they have diverted from the landfill. “Last year we diverted over twenty tons. Since we’ve started, we’ve diverted over forty-five tons.”

Ryan Bukowski and Jake Wells, who are both a vital part of Turnip Green, join us. Ryan is the gallery coordinator; he does everything from working directly with the artists to building the gallery walls. Jake is a board member of Turnip Green, an artist, a teacher, and a workshop leader. “I’ve been around for all of those five years,” Jake explains. “And I’ve really only been in Nashville for about six years. Before I

was here, I was in graduate school, getting a master’s degree in painting. My work was really about ecology, and I didn’t have a lot of money, so I was always about repurposing material. I got that from my family. My grandma was always one of those types who used every rag until it was a strand, then she might use that strand to tie her tomatoes up outside. So I come from a background of reusers.”

As “green” movements have taken shape around the country, the general public has become more interested in recycling. The issue, however, is that the right way to recycle has not been given as much attention. The phrase goes, “Reduce. Reuse. Recycle.” But unfortunately, the reuse part often gets overlooked. Recycling should always be a last resort only if something can’t be reused in a new way. The reasoning behind this is that recycling is a complicated process, often using a lot of energy. “It should be reduce, reuse, then recycle, but the reuse piece has to be bigger,” Kelly says. “But what happens is ‘recycle’ becomes bigger . . . reuse has to become bigger in order for us to really make an impact . . . [reuse] is what community waste departments deal with all over the nation . . . We work with Metro Beautification to try to teach people how to recycle right through art and education. One of the things they are coming up against is that when people don’t recycle right, it actually completely contaminates huge batches of materials, and that’s the problem. We got everyone thinking about recycling and reusing, and now we have to teach them how to do it correctly.”

“What we’re doing here is the artistic angle of reuse,” Jake elaborates. “It’s not just reuse for the sake of it— it’s creative reuse. It’s all the mad potential that comes with that. Kids can see so many things out of this piece of waste. They can make it into something else. When I was a kid, the trash can was my other toy box . . . What we’re really doing here is trying to be a kid again, tapping into that whole creative side, and then suddenly the possibilities really open up. Suddenly, it’s not just waste, it’s not just one thing . . . And it can be functional or it can just be aesthetic . . . I know I’ve certainly taken those plastic bottles and cut the bottoms off and used those as grommets on sculptures I was hanging. You start to see that everything has potential.”

What Turnip Green aims to share with Nashville and beyond is a sense of artistic awareness when it comes to waste. Before you throw something away, try to imagine if it’s something an artist can breathe new life into

Suggested Content

Chelsea Kaiah James

Why aren't there any ears sculpted onto the presidents of Mt. Rushmore? Because American doesn't know how to listen. - Unkown