The world of classical music is unfortunately—yet perhaps unsurprisingly—male-dominated. While it’s certainly not uncommon for women to perform in symphonies, operas, or choirs around the country, there’s still a staggering gender equality gap in classical programming and conducting.

According to a June study conducted by the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, only 1.8 percent of pieces performed by the top twenty-two US orchestras in the 2014–2015 season were composed by women. And as of 2013, out of 103 high-budget US orchestras, 90 percent were conducted by men.

Living composers (both female and male) don’t fair too well either. Roughly 11 percent of pieces performed by the aforementioned top twenty-two orchestras in the country were composed by living composers. But even among living composers, the gap remains: 85.7 percent male, 14.3 percent female.

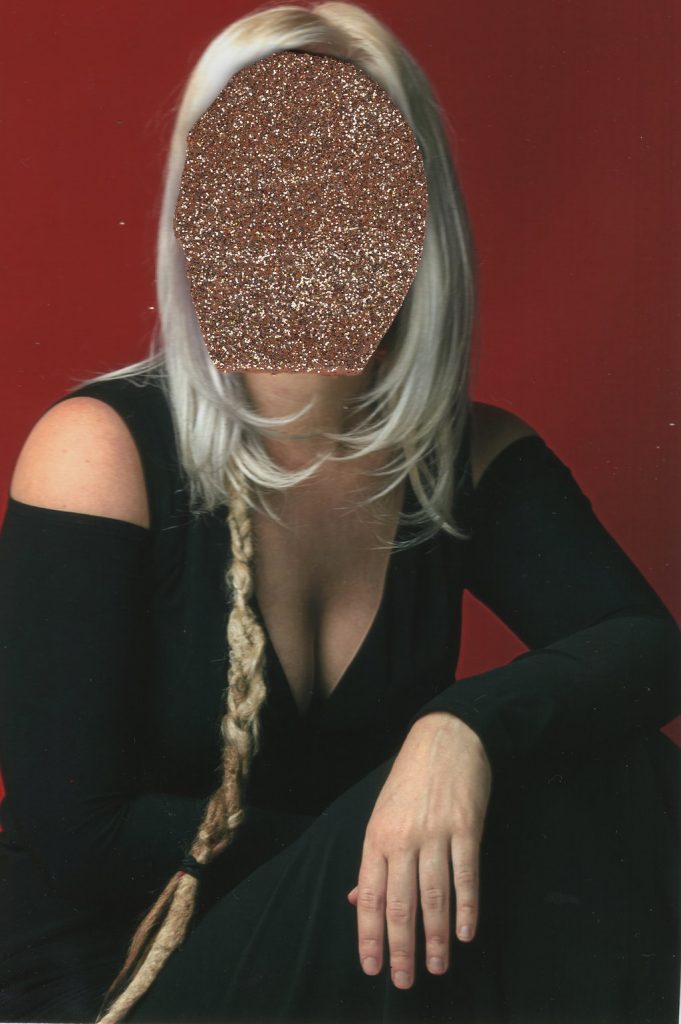

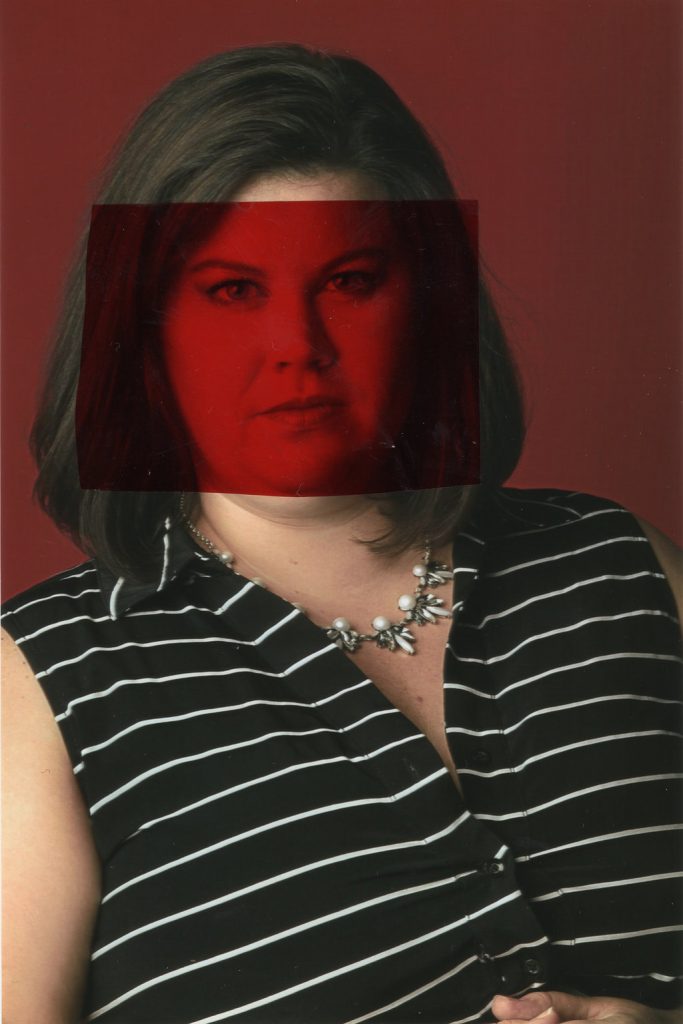

Luckily, Nashville is home to a host of women who are challenging the idea that classical music is created by and for a bunch of old (or in most cases, dead) men. We had the honor of partnering with the Nashville Opera to facilitate a roundtable discussion with three such women: Claire Boling, a soprano at the Nashville Opera; Timbre Cierpke, the harpist/vocalist/composer behind Timbre and director of Sonus Choir; and Kelly Corcoran, the artistic director and conductor of INTERSECTION Contemporary Music Ensemble.

ON NASHVILLE’S PERCEPTION OF CLASSICAL MUSIC:

CORCORAN: Generally speaking, I do think that the average person maybe if they haven’t experienced classical music and you ask them about it, they’re going to say, “‘I don’t know if I would like that,’ or ‘That’s not for me.’” There are these barriers. I don’t know if you guys would agree. I guess it’s better here because of the general culture of consuming music. It might be easier to get somebody to say, “Oh sure, I’ll try that,” but I think the barrier is still there for sure.

BOLING: I think we have to work really hard to break that and reach the younger audiences. The opera, you’re dealing with Mozart and all these people that were alive years and years ago. We have to pick stuff that would be more acceptable to someone in their twenties going to see a show—something that they can relate to. I think as a whole it is Music City, and Music City is open to all music and not just the country scene. I mean, the symphony center is right across from the Country Music Hall of Fame, for crying out loud. At least we got that going for us! [laughs]

CIERPKE: I think Nashville has a high percentage of artistic people and it draws artistic people. By definition, people in that personality are going to be more experimental and willing to try different things. I think they’re also more oriented toward experience, like having an experience. I think that’s something that classical offers that’s different from anything else. Even if [listeners] don’t have context for [a performance] but have experienced it before, they recognize it when they see it and then they want more of it. I think that’s an opportunity that happens in Nashville more than most places. It might be hard to get audiences there the first time, but once they have a good experience, they’re going to be dedicated to it. People in Nashville are so dedicated to music that once they find their value in it, they’re going to stick to it.

ON NASHVILLE’S PERCEPTION OF CLASSICAL MUSIC:

CORCORAN: Generally speaking, I do think that the average person maybe if they haven’t experienced classical music and you ask them about it, they’re going to say, “‘I don’t know if I would like that,’ or ‘That’s not for me.’” There are these barriers. I don’t know if you guys would agree. I guess it’s better here because of the general culture of consuming music. It might be easier to get somebody to say, “Oh sure, I’ll try that,” but I think the barrier is still there for sure.

BOLING: I think we have to work really hard to break that and reach the younger audiences. The opera, you’re dealing with Mozart and all these people that were alive years and years ago. We have to pick stuff that would be more acceptable to someone in their twenties going to see a show—something that they can relate to. I think as a whole it is Music City, and Music City is open to all music and not just the country scene. I mean, the symphony center is right across from the Country Music Hall of Fame, for crying out loud. At least we got that going for us! [laughs]

CIERPKE: I think Nashville has a high percentage of artistic people and it draws artistic people. By definition, people in that personality are going to be more experimental and willing to try different things. I think they’re also more oriented toward experience, like having an experience. I think that’s something that classical offers that’s different from anything else. Even if [listeners] don’t have context for [a performance] but have experienced it before, they recognize it when they see it and then they want more of it. I think that’s an opportunity that happens in Nashville more than most places. It might be hard to get audiences there the first time, but once they have a good experience, they’re going to be dedicated to it. People in Nashville are so dedicated to music that once they find their value in it, they’re going to stick to it.

ADVICE FOR NASHVILLIANS ATTENDING A CLASSICAL PERFORMANCE FOR THE FIRST TIME:

CIERPKE: If I had a friend who had never listened to classical music and they wanted to go to their first symphony concert, my personal idea would be for them to come to something that’s more emotionally engaging. For me that’s Romantic-era, Russian, or French composers, because I feel like [they’re] so dynamic, and even if you don’t have a lot of training, you can catch the emotion because it’s very much emotionally oriented. I would recommend against starting out with something like Mozart because it’s more formula and less emotion. Some people really connect to that, but I think if you don’t have a context for understanding the structure, it’s going to be boring for a lot of people. That would be my first suggestion: jump into the more dynamic composers, find a concert that has the Russians or something from the Romantic era. That’s going to be the most engaging.

BOLING: Turandot was the highest-grossing production [The Nashville Opera] has done. About ten of my friends who had never been to an opera before came to this one because it was a spectacle. It was grand. It was loud. It was emotional. The costumes were amazing. It was an experience that got almost all of the senses. I don’t know if you could taste the opera [laughs], but you could at least get the rest of them in there—[you could] feel the sound waves going through your hair. I think as far as an old classic, it’s great to have something that is just massive and a spectacle so they can really see how grand [classical music] can actually be.

CORCORAN: I think there’s two things functioning: the listening experience of how we engage with this music, and then the physical experience of going to a concert and whether or not you feel a sense of belonging. On the listening side, I totally agree with all that you guys have said about these Romantic pieces and these big masterpieces and just the full scope. I would say to somebody, “There is no right or wrong in terms of how you feel or how you react to this.” If you listen to this thing for forty-five minutes and you’re like, “Okay, I have no idea why, but I really enjoy it,” that’s okay. Your association and connection with the music will deepen the more and more that you listen to it.

ON DEFINING CLASSICAL MUSIC:

CORCORAN: I’ve put a lot of thought into this since there certainly was a lot of discussion when I started INTERSECTION about, “Should we be calling it composed music or something else?” Craig Havighurst, who is on our board, put this whole article together about making the case for calling it “composed music” . . . At the beginning, when I launched into this internal discussion, there was a period of time where I was like, “Well, I don’t really want to call it classical.” I almost felt like making apologies for the word classical. And then at a certain point I said, “You know what, I’m going to call it classical until we come up with a better word that really encapsulates all of it.”

CIERPKE: Honestly, I feel like that word is changing anyway. [With] the rise of so many neoclassical crossover artists and new composers, the name itself is changing. It’s being redefined just because of the people that are pursuing it. I think that’s more maybe what our role is if we feel like it’s got a stigma attached to it: let’s remove the stigma and recreate how it feels. I think that is happening. Even the idea of neoclassical, that’s the genre my band is in . . . that’s still being defined. To me, in my understanding, it’s usually classical instrumentation but more on the songwriting side. Or it’s also minimalism, like all these things just mushed together, but it’s all under this umbrella of classical, and I think that’s the point. It’s becoming less and less defined, and because of that, it’s becoming more and more accessible.

BOLING: Everything is a crossover, everything we do I feel like these days.

CIERPKE: There is no art that’s not influenced by something else—whether it’s influenced by other music or whether it’s influenced by literature or philosophy of the time. You can even look back at when Debussy was writing, you can see that you also had the impressionist artists. You can look at Monet and listen to Debussy and see how they completely go together. I think the same thing is happening now. Classical music is being deeply influenced by culture, and culture, whether it realizes it or not, is being influenced by classical music. Some of those boundaries that we set with our semantics don’t actually exist.

I’ve had those reviews in newspapers where at the end they say, “And she did it all in heels!”

ON THE PREVALENCE OF WOMEN IN CLASSICAL MUSIC LEADERSHIP ROLES, IN NASHVILLE AND NATIONALLY:

CORCORAN: I do think that there are a lot of strong creative women in Nashville, and I love having the camaraderie of my fellow strong woman creative colleagues in the city in artistic leadership positions. I’m not sure I would narrow that to conducting specifically, but just in terms of arts leaders in classical music, I think there’s a lot of great women in power.

But I think [the number of women in classical music leadership roles] is absolutely still an issue. I think it’s, frankly speaking, such a hard thing to talk about . . . I’ve had those reviews in newspapers where at the end they say, “And she did it all in heels!” and those kinds of things where it’s like, “Okay, but what about how the performance was? Was it necessary to say that at the end of the review?” That wasn’t here in Nashville. That was somewhere else . . . I think the fact that we’re at a point where it’s still this taboo thing to have female conductors, it means that obviously it’s still an issue. I guess what I’m trying to say is, [I used to] narrow the conversation to, “Well, I just think about the music and I just focus on the music and it all goes away.” But the reality is, I focus on the music, and it doesn’t all go away.

BOLING: I don’t deal with as much of the leadership as you two with your own groups and everything, but as far as the involvement, I’m only in one show a year because we have so many sopranos. There are tons of women involved in creating the music and wanting to be a part of things. We’re always looking for more opportunities so we can actually get in front of people and make music. Leadership, I think it’s still an issue, but I think we’re making leaps and bounds all the time.

CIERPKE: [To Corcoran] I so respect what you’re doing and how much respect you’ve garnered as a female conductor. That’s something that’s super, super lacking in the classical world. One of the symphonies that I played in, when they were going through an audition process for a conductor, there was one woman out of six people applying. Even in the orchestra, I heard so many comments. “She did great for a woman conductor”—that was a prevalent comment. You’ll hear people say, “She’s a good drummer for a girl” . . . There’s a qualification for it. There’s an expectation that it’s going to be lower value. That expectation is what we’re pushing against.