“I apparently don’t know how to back up to an iCloud or whatever,” says the sarcastic but sweet Amanda Shires: singer-songwriter, recovering fiddle side gal, and matriarch of Americana’s coolest family. She’s still fuming over a September tour van robbery that cost her a computer and her nearly finished master’s thesis in poetry, along with some new songs and assorted gear. “Like, what the fuck is an iCloud? What happens when the iCloud rains? All your pictures just land in other people’s yards?”

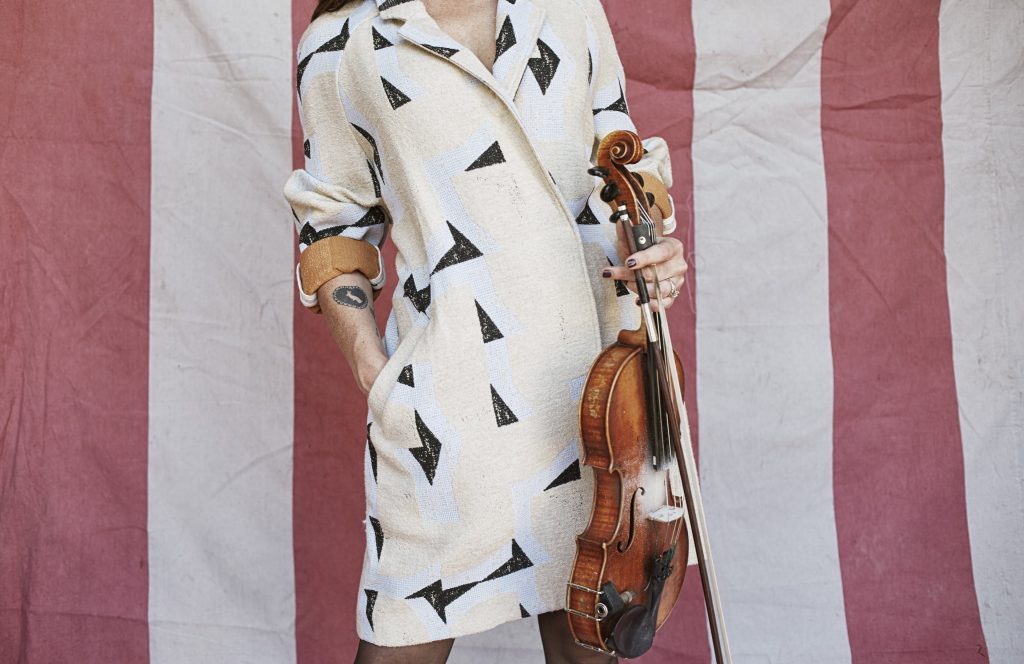

A thirty-four-year-old Texas smart aleck who started her career as a teenage fiddle player in The Texas Playboys, Shires might not be tech savvy enough for a job at Apple’s Genius Bar, but she is an expert in things like soul-baring music and verse—and she’s put that knowledge to good use after a roller-coaster ride of pre-parental anxiety.

My Piece of Land, Shires’ fifth album, was inspired, written, and recorded during the third trimester of her first pregnancy, a strange time when she was forced off the tour trail and into an exile of anticipation. While waiting for the arrival of daughter Mercy, Shires’ husband—Grammy-winning songsmith and roots star Jason Isbell—was out on tour, so she was stuck at home with nothing but her thoughts for company . . . and those quickly ran wild.

From shadowy worst-case scenarios to optimistic determination, Shires was able to capture the mildly insane nature of bringing new life into the world in almost-real time. Yet this collection is different from her previous work; it’s focused and vocal-based, relaxed but sophisticated. There’s less of her songbird warble (a nervous tell, she says), and the fiddle is downplayed.

Now sitting at a sidewalk cafe table on one of Nashville’s first cool days of fall, a busy avenue roaring over her shoulder and more than a year removed from those fretful weeks, Shires describes the descent into baby madness that made My Piece of Land her most revealing body of work to date.

“I was deep into pregnancy, and I started organizing all the drawers and cleaning the ceiling fans and setting the nursery up,” she says. “I did everything I could, and then I was done with all the distractions and I was left to face the reality and truth of bringing a child into the world and what that meant. Like, ‘Am I gonna be a good mom? How’s this gonna work with traveling? How’s this gonna work with being a songwriter? Will I still wanna do both things?’”

Produced by song-whisperer Dave Cobb (who also guided Isbell’s masterful Southeastern and Something More Than Free), the ten songs on My Piece of Land dart back and forth between excitement and exhaustion, each one facing another fear common to expecting mothers but brand-new to Shires. Along the way she answers a few of her own questions and, in the end, realizes there’s no “right way” to raise a child. But it wasn’t an easy road.

“In that moment I didn’t know everything was gonna be just fine, and a lot of that was probably due to hormones,” she says with a smirk, half apologizing. “But I came from a family where they’re divorced and they’ve each been married like a hundred times, so I was like, ‘I don’t want that to happen to [Mercy].’ . . . I don’t think it will, but I started thinking about all that stuff and then going down the rabbit hole.”

“Slippin’” is one such trip down the rabbit hole, a standout with its delicate melody and impending-doom lyrics. At the time she was feeling “really huge and uncomfortable,” she explains, and imagined Isbell saw her the same way. Then she wondered, “What if that makes him fall off the wagon?”

“It’s a truthful, honest feeling of insecurity that happened then and occasionally happens now,” she explains, almost ashamed to admit it. Isbell has been sober since she helped get him there in 2012. “An addiction to alcohol is different than an addiction to drugs. You can drive into any grocery store or gas station and get anything you want, and you see signs like ‘Buy this beer!’ or ‘Buy this whiskey!’ There’s no ‘Buy this crack!’ signs to remind you. I worry for him sometimes, but he’s doing well.”

Likewise, “Harmless” finds Shires contemplating her own level of commitment. Beginning with a poetic description of a stranger on the street and a fleeting rush of desire, she bravely wonders aloud how far she might go.

“Imagine a streetlight that falls across somebody,” she says, setting the scene, “and somehow the light is magical and makes them look super awesome, and you just want to explore that but you know there’s a line you can’t cross. But where is the line? Is thinking it crossing it? And was it harmless? Who knows.”

“When You’re Gone” takes a different route to the same mental space, approaching loneliness with an upbeat, highway-rock feel—“I wouldn’t call it silence / It’s a different kind of quiet”—while “The Way It Dimmed” kicks off the project with playful hand claps and an admission that fires do sometimes burn out.

Those thoughts were intense but ultimately short-lived, as there was never any real doubt about her and Isbell’s bond.

“Sometimes, it’s best just to say something, just to see how silly it sounds,” she admits.

Eventually Shires came to a moment of clarity that gave her album its theme—and helped her become the mother she was scared of failing to be. It’s a simple but impactful concept: Home doesn’t have to be a place.

“I started thinking about what [Mercy’s] home was gonna be like and what it would mean to be traveling all the time,” she explains. “Would she even have a real sense of home? And I sort of came around to figuring out that home is more fluid, and it’s not really anything to do with an address. . . . Really for me, it’s all about being with the people I love, and that could be anywhere.”

This was the root of Shires’ worry, it seems, as the divorce of her own parents left her with a poor sense of “home.” You can hear it in “Mineral Wells,” an older song that reappears here with a new meaning. What once was a tree that belonged nowhere—it had roots and leaves in two different Texas towns—is now proud of its unique nature. “I still really need that song for some reason, so I like to play it,” she admits.

Meanwhile, “You Are My Home” solidifies her new embrace of an untethered life, a determined, hell-or-high-water oath to Isbell and Mercy. It’s full of resolve yet slightly dark, nodding to the challenges that are sure to await, but it features a reassuring guitar solo from Isbell.

Isbell shows up in various ways throughout the album, co-penning two poetic songs—check out the “eagle-feathered roach clip” line in “Pale Fire” and the welcome destruction caused by “My Love – The Storm”—while also providing harmony vocals and stellar guitar support all around. For her part, Mercy inspired not only “You Are My Home,” but also “Nursery Rhyme,” easily the most joyful track on the album. Full of whimsy and the teetering rhythm of a baby taking her first steps, it’s a heartwarming conversation between mother and unborn daughter, completing the 360-degree revolution of emotions.

“It was a wild ride,” Shires says.

Incredibly, Mercy also shows up in a much more tangible way on My Piece of Land—she’s actually on the record, if you know where to look.

“If you were to isolate the ukulele I was playing on ‘Mineral Wells,’ you can hear her kicking,” Shires beams with pride. “Dave Cobb did isolate it once for me so I could hear it. When we first started recording they were like, ‘What’s that noise?’ We stopped and we were checking the gear and stuff, and it was her, so we just recorded through it.”

Cobb played a huge role in the project, she says, by letting each song go where it would and helping her to strike while the iron was still hot. From writing to recording, the whole process only took a few short months, and Shires gave birth just days after work was finished. Cobb’s preferred method focuses on spontaneity and fearless experimentation, so he encourages artists not to finalize their songs until recording begins. It tends to highlight the connection between head and heart, a feeling Cobb is famous for capturing on records like Chris Stapleton’s Traveller.

“I really, really love the thing where you don’t play your songs, you don’t do demos, you don’t even learn them, really,” she says. “You just write the songs and then revisit them [in the studio], and it turns into a real creative project. Everybody has suggestions. If I would have written the songs and practiced them, they would have come out like a lot of my other stuff, and I have a tendency to put more stuff on a recording than there needs to be.”

Indeed, parts of My Piece of Land are downright spartan, focusing on Shires’ voice and writing in a way she has never done before. There’s also less fiddle on this album than her previous four, and she thinks Cobb led her that way on purpose—nudging her toward the true singer-songwriter she wanted to be after first arriving in Nashville almost a decade ago.

“Being a side person for so long and being perceived only as a fiddle player, I sort of told myself I had to do that on every song no matter what—and it’s not true,” she says. “I think he intentionally made it less fiddle heavy so I could stand on my own as a songwriter.”

These days, Shires has reached the other side of her pregnancy jitters. Mercy is now a year old, and Shires says being a mom is “the best in the whole wide world.” The fears about her marriage and Isbell’s sobriety turned out to be unfounded—“He’s a great dad,” she says, looking off somewhere into the clouds—and the only worries now are the separate tours that will soon pull the family in opposite directions. Mercy will ride with Isbell on his bus, while Shires will be roughing it in the band van for three agonizing weeks. Her headlining trek then continues with coast-to-coast club dates scheduled through December 10.

“FaceTime is so awful,” she says. “[Mercy] gets kinda upset because she doesn’t understand you can’t hold the computer screen. It’s cute.”

She may have come to terms with Mercy growing up a child of the road, but it actually seems that Shires is busy creating a more traditional kind of “home,” too, just in case. The young family recently moved into a house just outside Nashville, one nestled into a few peaceful acres with a barn they hope to turn into a performance space.

It’s their own literal piece of land, the kind of place that will come with its own set of challenges. A place where long-lasting memories will be made. This time, though, she’s not worried about doing things the “right” way—they’ll just do it their way.

“I’m so excited, and Jason is like, ‘I get to mow grass!’” she says, reverting back to sassy, smiling sarcasm. “But he’s also the kind of grass mower that when he got his mower, he put the key in it and broke it off. So we’re awesome at living in the country . . . but we’re gonna get better at it.”