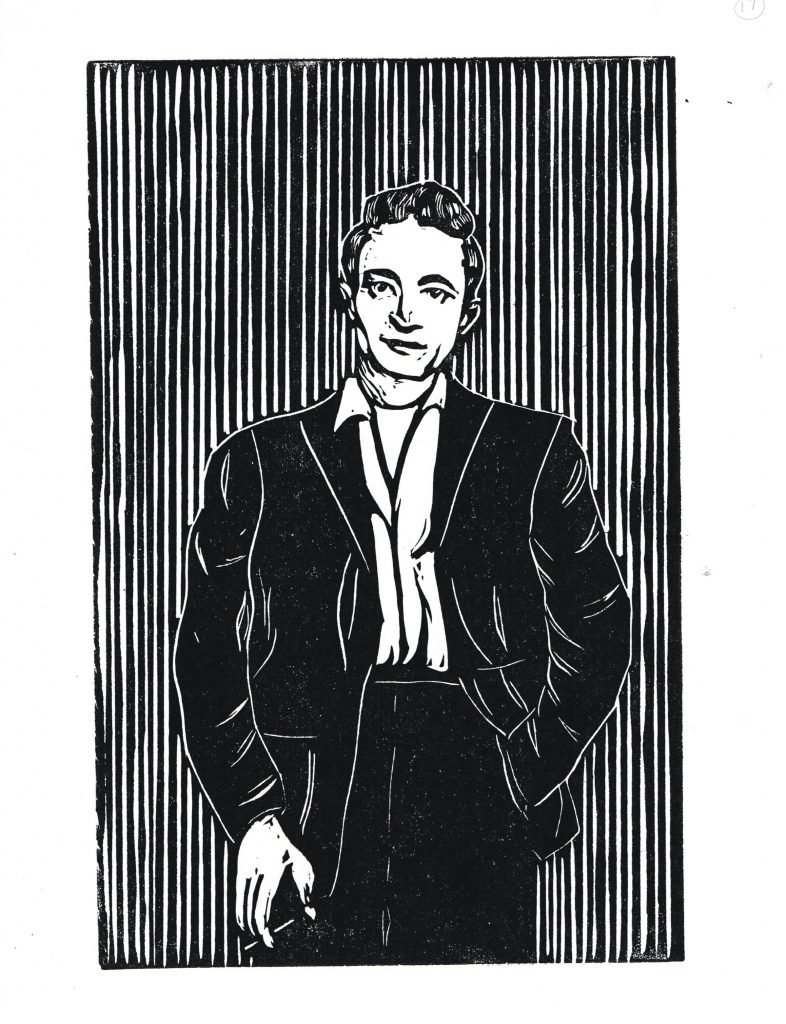

“SOMEHOW JOHNNY CASH IS DEAD.”

In those five words, Peter Cooper, writing for The Tennessean’s 2003 obituary for Johnny Cash, encapsulated how every country fan, and perhaps every music fan, felt that September. “Somehow” this elemental force—this symbol of pain, tragedy, and triumph that would surely outlast the rest of us—was really gone. It was like the wind had suddenly decided to stop blowing or the grass had turned blue. The Man in Black had faded to black, and Peter Cooper was right there with us, mourning.

But Cooper has always been “right there.” And he’s always known exactly what to say and when to say it.

Country-folk god endorsements aside, at the end of the day, Cooper is a storyteller. And he’s perhaps never told better stories than in his new book, Johnny’s Cash and Charley’s Pride: Lasting Legends and Untold Adventures in Country Music.

Like most things that are good, it’s hard to classify the book: it’s a memoir; it’s an encyclopedic record of the Old Testament-esque origins of country music; it’s a behind-the-scenes look at legends struggling with mortality and legacy. In it, you’ll find now-classic Americana myths—like the time Kristofferson landed a helicopter on Johnny Cash’s lawn, or George Jones drove a riding lawn mower to the liquor store—told in a new context. You’ll also find a humanizing interview with a young Taylor Swift, a surreal story about Lee Ann Womack threatening to kick Cooper in the balls, and a heartbreaking look into the tragi-comic life of Jimmy Martin.

But more notably, you’ll find stories and people that have (wrongly) fallen through the cracks of history. There’s enigmatic cult figure “Cowboy” Jack Clement—a producer/songwriter that worked with Sam Phillips, helped make “Historic RCA Studio B” historic, and recorded everyone from Waylon to Bono in his home studio off Belmont Boulevard. There’s Station Inn matriarch Ann Soyars, who arguably discovered Chris Stapleton and Dierks Bentley. There’s Lloyd Green, the “Sandy Koufax of steel guitar,” who turned down a touring position in Paul McCartney’s Wings.

They’re all remembered with dignity, sincerity, humor, and heartfelt conviction—with writing that’s tight and clean and erudite and all those other words writers use to describe good writing. As perennial rock critic Peter Guralnick says in the foreword: “[Cooper] offers brilliant, and funny, portrayals of their magnificent eccentricities without ever showing a hint of condescension—and without ever failing to suggest the depths of perception, insight, and regret that may well lie underneath.”

The following are Cooper’s edited ruminations, anecdotes, and general thoughts from the afternoon we spent at the Omni Bongo Java, next door to his office at the Hall of Fame. They’re great, but if you want the real deal, I suggest picking up a copy of Johnny’s Cash and Charley’s Pride. You won’t be disappointed.

ON “COWBOY” JACK CLEMENT

Cowboy, for so many reasons, exemplifies Nashville, the best of Nashville, to me. I wish everyone who puts a bid down on a house here could be able to meet him and understand. Or would have been able to meet him and get a sense of that guy. I start the book with, “Well we should probably start with the Cowboy. He’s the one you should have met.” And I genuinely think that. It’s not that people need to memorize his resume or know what hit songs he wrote or something. It’s the essence of the dude that I’m trying to sprinkle around.

[The essence was] unfettered, whimsical, creative insanity, underscored by the notion that if we’re not having fun, we’re really screwing up. When Cowboy entered a room—at least up to a certain point in the vodka bottle—the room got happier, and people felt better about themselves and better about the things they were doing. A clown prince is still a royal. You should have met him. He was just a delight.

So much great stuff got done because of him and the way he wanted to work. He decided that maybe a studio is the worst place in the world to make music, so he turned his house into a studio. That was the model for everything that all of us are doing these days. That was taking back the creative reins—let’s do it at the house. Then he decided to paint the stairwell up to the second story studio and have it be blue sky and clouds. It really felt like you were ascending when you were there at his home on Belmont Boulevard. If you took a guitar and its case up those stairs, you felt like you were moving on up to some place holy—because you were.

ON THE LINE BETWEEN CATHARSIS AND SELF-DESTRUCTION IN SONGWRITING:

I think that songwriting is different things for different songwriters. And I think that sometimes it is self-destructive, and I think sometimes it is soul sustaining. There are people who write their way into problems and people who write their way out of them. I think when you are songwriting at the level of the kinds of people that we’re talking about, you’re playing blackjack at the high stakes table. It’s not an easy thing, and it’s not something to be taken lightly—that these people open themselves up on a level that’s uncommon, even among parents and children or marriage partners. They are opening themselves up to complete strangers. For some of them the way that strangers deal with that is of no consequence, and for others, it just grinds at them.

I think empathy is the necessary element and that some people acquire empathy for damaged people by damaging themselves . . . But, I also think that there are people who have a Hank Williams complex and work on destroying themselves in the name of creativity. That doesn’t enable their creativity at all.

I think of one of my favorites—that’s why I didn’t write much about him in the book. Townes Van Zandt is an incredible songwriter but spent the last ten years of his life not creating very much because he was an addict. You can fool yourself into thinking you’re Hank Williams, but Hank Williams also died at age twenty-nine. Who knows what great work he would have done.

ON CRITICISM IN WRITING:

I think there are ways to write critically about art and about politics that aren’t snarky. I just think sometimes that it’s the cheap way out, and it’s not a great way to make a point. Putting something down is not a way to further your agenda . . . [It’s] like the people yelling at each other on the Sunday talk shows from polar opposite points of view: they never convince each other of anything. They’re just yelling and maybe someone gets a gotcha in there, but minds aren’t changing there.

I think that people do that with music sometimes too . . . There were several times I remember coming up with something really snarky and funny and chastising. To the point that I laughed as I typed it. Inevitably, those are the sentences that I would regret when they got into print and I stared at them. Anything written out of meanness is not going to help.

I don’t root for music in the same way that I root for sports teams anymore—I’m glad I don’t. I can spend time spending my allotment of hate on Duke basketball or something and not on some song that doesn’t strike my fancy. Every moment I’m spending on paying attention to something that doesn’t strike my fancy is a moment that I’m not spending finding something that does.

ON “FUN” IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY:

I think when the music business isn’t as fun as it used to be, it’s probably our fault. With that said, lack of privacy is a bitch. In the ’70s, Waylon Jennings was doing business at three in the morning over a pinball gambling machine at JJ’s Market. That kind of thing just can’t be done today. Everything is worldwide as soon as it happens. We’ve got email verification, and cellphone records, and Taylor Swift can’t go for a walk in the park without everybody knowing it. So, that probably produces a different kind of popular recording artist, because you can’t make the reckless mistakes in private. And making big reckless mistakes was part of the artistic process at one time.

That said, music should be fun. One big point of the book is Cowboy Jack’s notion of, “Remember we’re in the fun business, if we’re not having fun, we’re not doing our jobs.” It should be a joyful thing and in some corners it certainly is. There’s not a lot of great reasons to do it if it’s not joyful, and if it doesn’t provide for some kind of relief. The business model is [lousy] at this point. There’s every indication that the choice to make music for a living is going to provide for some measure of heartache and hardship.

ON THE INTERSECTION OF HUMOR AND TRAGEDY IN COUNTRY MUSIC:

I don’t know how to define it, but I know often its appeal is kind of like a really good episode of M.A.S.H. . . . It’s humor that just sets you up for an emotional sucker punch. When you laugh, you’re opened up. The best at this is John Prine—you’re chuckling so you’re open to what’s coming next, and then he says, “There’s a hole in daddy’s arm where all the money goes / and Jesus Christ died for nothing, I suppose.” That’s tough to ignore.

ON THE FUTURE OF COUNTRY MUSIC:

Well, we’ll strum a G chord and find out. See where it goes [laughs]. The infinite possibilities of the thing are mind-blowing to me. Where I’ve taken it lately is making an album, writing an album with Thomm Jutz and Country Music Hall of Fame member Mac Wiseman, about the scope of Mac’s life and his experience [going] from an impoverished child in rural Virginia to world-traveling Hall of Fame musician. Sitting with him and having him tell his stories, and writing those down and making sure that they rhyme at some point—that’s nothing I could ever have predicted that I would be doing.

Mac picked up a guitar, started recording in 1946, and was in Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys, and Flatt & Scruggs and the Foggy Mountain Boys, and helped invent bluegrass. Music brought him to Nashville. Because of this WSM Radio tower that’s here. They can pump out fifty thousand watts of power and take a local musician and make him a national musician.

In some ways, this book isn’t about Nashville, but I do want people to come away from it with an understanding of why this town is what it is. And who these insane geniuses who populate this town are, and were, and will be. It’s incredible to live here.

ON MEETING YOUR HEROES:

Some people feel like musicians are pulling some kind of trick on them. [They say], “You wouldn’t want to meet so-and-so because you’d really be disappointed.” With songwriters, that’s stuff that you cannot fake. You can’t fake Kristofferson’s intelligence and empathy and humanity and inherent goodness. He would not be able to write those songs if he did not possess those qualities. You can be a total dick and a really good defensive end, but I don’t think you can do it with songs. At least I haven’t come across it. That doesn’t mean that I haven’t met jerk songwriters, but invariably they’ve been people whose songs didn’t move me much.

The club that I’m writing about is one that lets me come in on visitor’s day and peer in the window, shake hands every now and then, but I’m not a member. These are people who changed things . . . All these people had their lives changed by music before they went and changed music. They all ran to it, you know? They saw the fire and decided not to flee.

Johnny’s Cash and Charley’s Pride: Lasting Legends and Untold Adventures in Country Music is available April 25 via Spring House Press.