THE FIRST TIME I SAW CAGE THE ELEPHANT, frontman Matt Shultz was climbing the scaffolding of Bonnaroo’s That Tent while wearing a red spandex bodysuit that had a syringe and a pill printed on it. A crowd surfer kicked me in the head, a security guard slammed a kid face-first into the stage, and someone official-looking told me to “back the fuck up” as I tried to join the twenty some-odd fans that had clawed their way onstage. I left feeling like I’d accomplished something—like it was a feat to survive Cage the Elephant live.

Back then, in 2009, this was the sort of spectacle that defined Cage. They were baby-faced Kentuckians with a reputation for raucous live shows and a chart-topping single about prostitutes, crooked preachers, and muggers. And in a year dominated by the likes of Lady Gaga, Phoenix, and “Use Somebody”– era Kings of Leon, that was refreshing. It was gritty, no-frills rock made by gritty, no-frills dudes.

Seven years and three albums later, it’s an understatement to say that things have changed. Cage has sold out arenas with The Black Keys and Foo Fighters, survived a major lineup change (former lead guitarist Lincoln Parish left amicably after 2013’s Melophobia to focus on producing), and, following their 2014 appearance on The Late Show, inspired David Letterman to exclaim, “I mean, my God, really, that’s it. No more calls, we have a winner!” The boys from Bowling Green have done good—and then some.

Melophobia, the album that played a major role in spawning these opportunities, saw Cage adding horns, strings, and an Alison Mosshart feature to their traditionally bare-bones guitarbass-drums-vocals instrumentation. Lyrically, Matt turned inward, trading narratives about degenerates and kids worrying about haircuts for reflections on ennui and mortality. Suddenly, Matt—the guy who’d danced to Lil Wayne’s “A Milli” while wearing a pink tutu in a now-infamous YouTube video—was singing lines like, “From room to room he moves about / Fills his life with pointless things / And wonders how it all turns out.” The album established them as a twenty-first century anomaly of sorts: a straight-up rock band that could please critics, get airplay, and sell tickets.

Cage earned their first-ever Grammy nomination for Alternative Album of the Year with Melophobia, and on the support tour, they revisited nearly every major American festival, taking stages that were twice the size of the ones they’d played three to four years earlier. Now, they find themselves in an interesting position: What do you do for the follow-up to your biggest album yet?

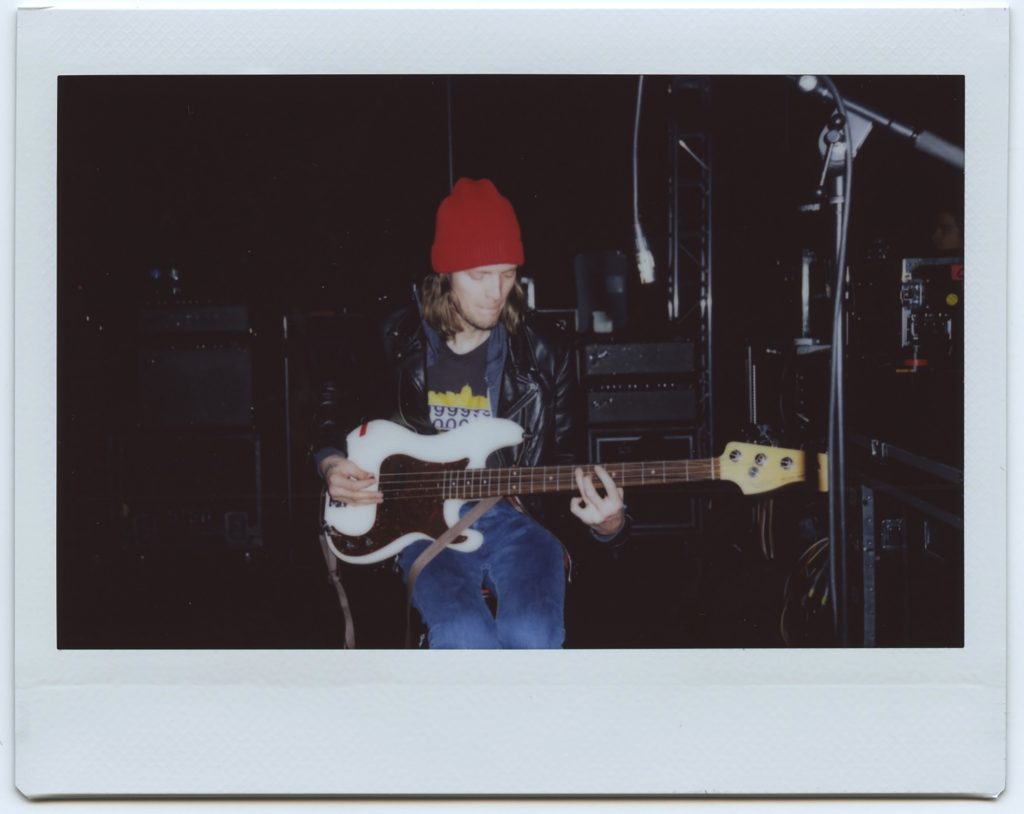

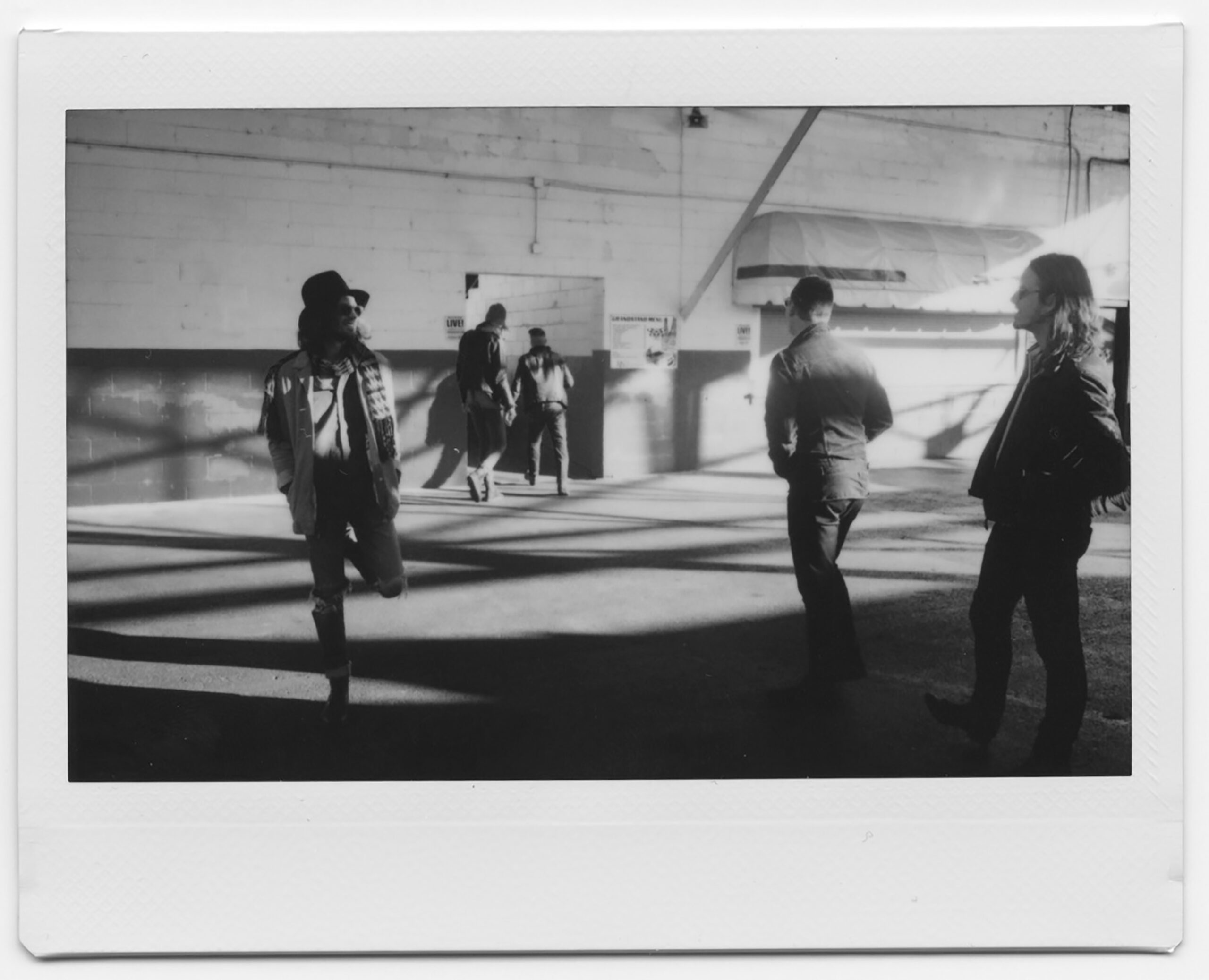

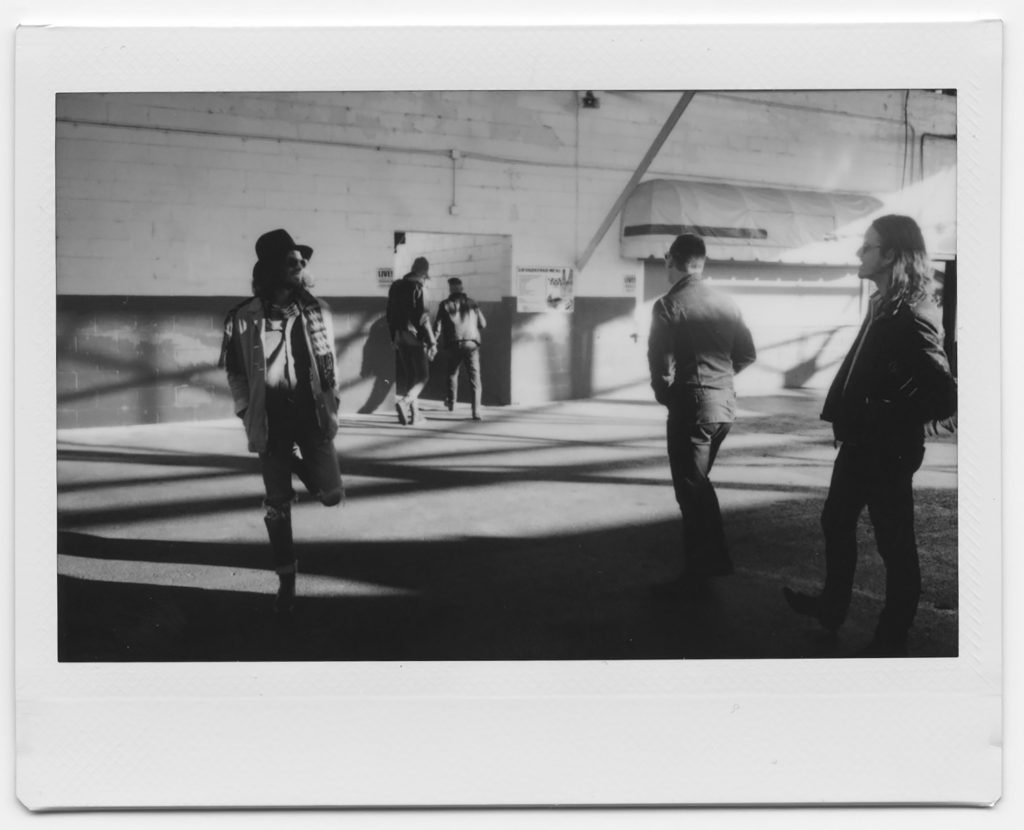

This morning, after a round of disc golf near bassist Daniel Tichenor’s East Nashville home, Cage doesn’t seem too worried about that question. They’re smoking Parliaments, singing the praises of Chrome Pony (who they’re seeing tonight at The Basement East), and discussing Two Ten Jack’s Brussels sprouts. It’s a rare slice of non-tour life in Cage’s adopted home, where most of the guys have taken up the domestic routine—four out of the six are now married, and two have kids. Guitarist and Matt’s brother, Brad Shultz, later laments that their upcoming outings— a quick West Coast run, an appearance on The Late Late Show with James Corden, local release shows at Studio 615, Grimey’s, and The Basement East, and a looming European tour—will be the first where his daughter is old enough to actually realize he’s gone.

Ungodly scheduling aside, Cage is proud to spend their ever-diminishing free time in Nashville. They beam over local acts such as Turbo Fruits, Fly Golden Eagle, Ranch Ghost, and Clear Plastic Masks, and they speak of Be Your Own Pet, MeeMaw, and now-demolished house venue Glenn Danzig’s House with earnest reverence.

“I mean, I’ve thought about moving anywhere in the United States, and the only place I want to live—and the only place I imagine myself living in—is Nashville,” says Nick Bockrath, who, along with multiinstrumentalist Matthan Minster, is the newest addition to Cage’s lineup. They were both recruited through fellow Bowling Green natives Morning Teleportation, and Nick used to play with local singersongwriter Rayland Baxter.

“[Nashville] has been hugely influential,” Matt adds. “We’ve made a lot of great friends too. There’s a purity in the approach that I wouldn’t say is unmatched, but it’s just . . . the bands that are making music here are supercharged for their cause. And that’s to be admired.”

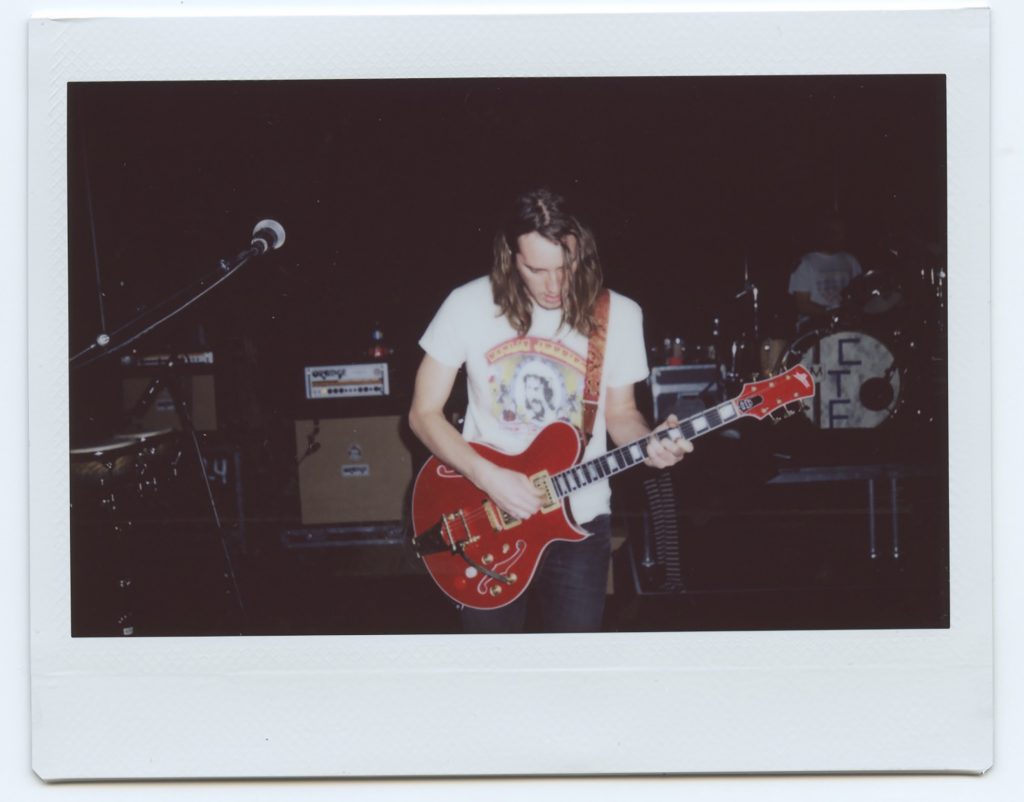

Given their tour history and affinity for Nashville-based acts, it’s not a shocker that Cage tapped The Black Keys’ Dan Auerbach to produce their latest album, Tell Me I’m Pretty. Not only is the album their first without Lincoln, the guitar wunderkind who’d first joined Cage at fifteen years old, it’s also their first without local producer Jay Joyce.

“We knew the direction we were going in for this record and knew we were looking for a raw, grittier sound,” Matt explains. “And when you think about guys on the production side, there’s not a lot of people that are doing that kind of thing at the level Dan is.”

Matt’s emphasis on rawness is echoed by the rest of band throughout the morning, which makes sense when you consider the sound of and process leading up to Melophobia. Sure, the album has its fair share of aggressive noise rock (see the jarring “Teeth” and “Spiderhead”), but it also shows Cage at their most polished. If Melophobia— with its ambitious arrangements, layers on layers of overdubs, and months-long recording process—is Cage’s Imagine, Tell Me I’m Pretty is their Plastic Ono Band. It’s a sparse, somber bit of expressionism that was recorded in less than a third of the time it took them to complete their last record.

“Melophobia is what we needed to bring us to this record,” Brad says. “We got a lot better at understanding each other throughout that process . . . Honestly that record was hell to make. And it’s kind of cliché, but when you go through something like that, you grow closer.”

Tell Me I’m Pretty’s straightforward nature can also be attributed to Dan, who encouraged Cage to value spontaneity over perfection. Scratch vocals were used throughout the album, guitars were left gnarled and raspy, and some songs, like the slinky, melancholic “How Are You True” were even knocked out in one take. During the sessions, Dan would also play esoteric records— like Brazilian garage rock—from his personal collection to help inspire the guys.

“It became this game in the band to try and figure out what Dan was playing us. We couldn’t even Shazam it,” Brad says, laughing. “Me and Nick would be like, ‘Cool, what’s that?’ And he’d just [answer], ‘Yeah,’ and kind of turn his iPod away and walk away . . . He just gets you into a really creative headspace.”

That creative headspace yielded a Cage record that strays even further from their ’90s alt-rock roots than Melophobia. It’s their most cinematic effort yet, coating everything from neo-noir to surf rock to rockabilly with a Syd Barrett-y sheen. Sonically, you could make the case that it’s a love letter to the Beatles, Tommy James and The Shondells, and Joe Cocker records that the Shultzes grew up listening to with their parents. The album even begins with a muddy, galloping bass line that calls to mind The Shondells’ “Draggin’ the Line.” It’s a collection of honest, three- to four minute songs made by a group of guys who love honest, three- to four-minute songs.

“For the first time in a long time, it kind of felt like we were those same kids in Bowling Green, Kentucky, getting together, jamming, making music,” Brad says. “Creatively, I felt like there was a weight lifted off of my chest. Like I could create songs and have fun with it.”

The process was less romantic for Matt. On the one hand, his efforts to shed the characters and storytelling that characterized earlier Cage releases have produced some of his best lyrics to date. On the other, the introspection he’s replaced those stories with takes an emotional toll. It’s a doubleedged sword that he hasn’t fully come to terms with. “With each record, I’m trying to be more and more transparent. And at a certain point, it becomes kind of uncomfortable. It’s like, this is basically a journal entry. Some of it felt a little too close,” he reveals.

These journal entries come out most notably on “Trouble” and “How Are You True,” a pair of ballads that serve as the centerpiece of the album. The former depicts a scenario in which two people sit down to have the ever-dreaded “deep talk,” but midway through the conversation, one party begins to wonder if the whole process is anything more than pageantry. Over a grandiose fuzz line that sounds like The Stooges playing The Phantom of the Opera riff, Matt pleads: “Got so much to lose / Got so much to prove / God don’t let me lose my mind.”

“There are times where things in your life become so valuable. And when it feels like everything is closing in around you, the idea of imminent doom can start to weigh pretty heavy on your mind,” Matt says. “[‘Trouble’] is about waiting for life’s next big blow, I guess.”

Brad shakes his head and gives an almost bemused smirk. “That really has been me and Matt’s whole life. When times are good, it always seems like . . .” he trails off before Matt, who looks like he’s still thinking about “Trouble,” cuts back in.

“There are different seasons in life. There are peaks and valleys. I think for a long time I’ve been afraid of the valleys, but, you know, we’ll see where life takes us. They’re both important,” he pauses, almost as if to reassure himself that he’s right. “They’re both important.”

The idea of accepting the valleys and honestly presenting them relates to the album’s title, which is a partial reaction to the personas people cultivate through social media. “We live in a selfie generation where we’re constantly curating the presentation of our lives,” Matt begins. “And it’s this presentation of only highs, so it’s this unreachable . . .”

“Unbalanced perception of life,” Daniel says in his even-keeled baritone while staring at the ground. Coming off of Brad and Matt’s animated back-andforth, it’s an almost startling change in the conversation’s tone. Like Daniel is the Elwood to the Shultzes’ Jake.

“Exactly,” Matt continues, more reserved. “Not only that, but people are dying to be accepted or loved and [want to] force you to accept them. And honestly, I’m not against social media in any regard; we all have our own choice on how to use those things. And everyone falls into those pitfalls in life, and we all have done it at one time or another . . . We always counter reality with imagery we project.”

Perception is a topic Cage has addressed throughout their career, on songs like the satirical “Indy Kidz” and the record industry put-down “Sell Yourself.” Even their second-ever single, 2010’s “In One Ear,” broaches the subject: “They say that we ain’t got the style, we ain’t got the class / We ain’t got the tunes that’s gonna put us on the map . . . So all the critics who despise us / Go ahead and criticize us.”

Cage has always been adamant about making the records they want to make, with little regard for the expectations surrounding “high culture” or “art” rock. As Brad bluntly puts it later in our interview, “It’s all about just making music. You don’t want any of that shit in your mind when you’re making a fucking song.”

It’s an attitude that aligns them—at least in terms of ideology—with fellow blue-collar bands throughout rock history, from Oasis to Lynyrd Skynyrd. It won’t land them in Pitchfork (who, to this day, has only mentioned Cage once in passing) anytime soon, but they really don’t give a damn about being in Pitchfork anyway.

“If you’re making music to be perceived as some intellect—or God forbid a genius—or for any reason other than to communicate an intentional thing, an intentional expression, you’re teetering a dangerous line,” Matt argues. “If you stay true to that conviction and your intention in that thing, then I think you’re moving toward something that’s going to be cathartic for you and hopefully reach other people. When you’re outside those lines, then you’re playing with people’s sensibilities—then you’re trying to reach their filter of cool . . . Then you’re just an accessory.”

Matt eases back into his seat and crosses his legs. Then, with a Kanyeesque shrug, he adds, “I don’t want people to change me like they change their shoes. I wanna make stuff that’s deeper than that.”

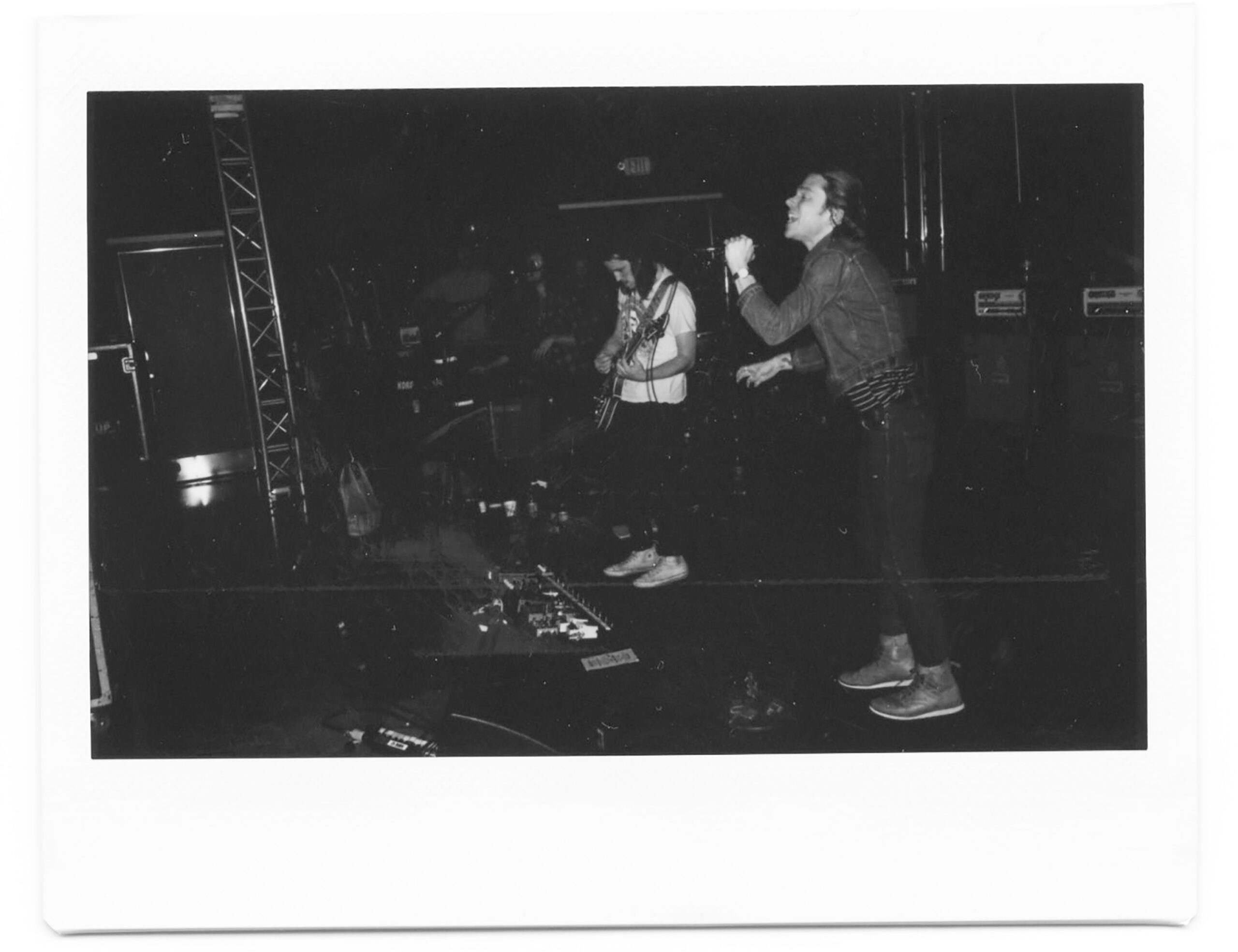

Two weeks after our interview, I’m maneuvering through a four-hundredperson crowd at The Basement East for Cage’s aforementioned release show. It’s the latest in a series of intimate local shows they’ve been doing since a 2014 gig at Mercy Lounge—all of which have almost immediately sold out.

And tonight’s no exception: a solid crowd is already assembled before openers Clear Plastic Masks even start, and before the show, somebody claimed that tickets were being sold for as much as $300 on some dark corner of Craigslist.

After a charged version of “Cry Baby” in which Matthan’s backing vocals shine, Matt takes a second to catch his breath before yelling, “Feels good to be back home in Nashville. Home, sweet home.” The crowd predictably goes wild—especially the pogoing Rivers Cuomo ringer and selfie-taking (sorry, Matt) middle-aged couple I’m sandwiched between.

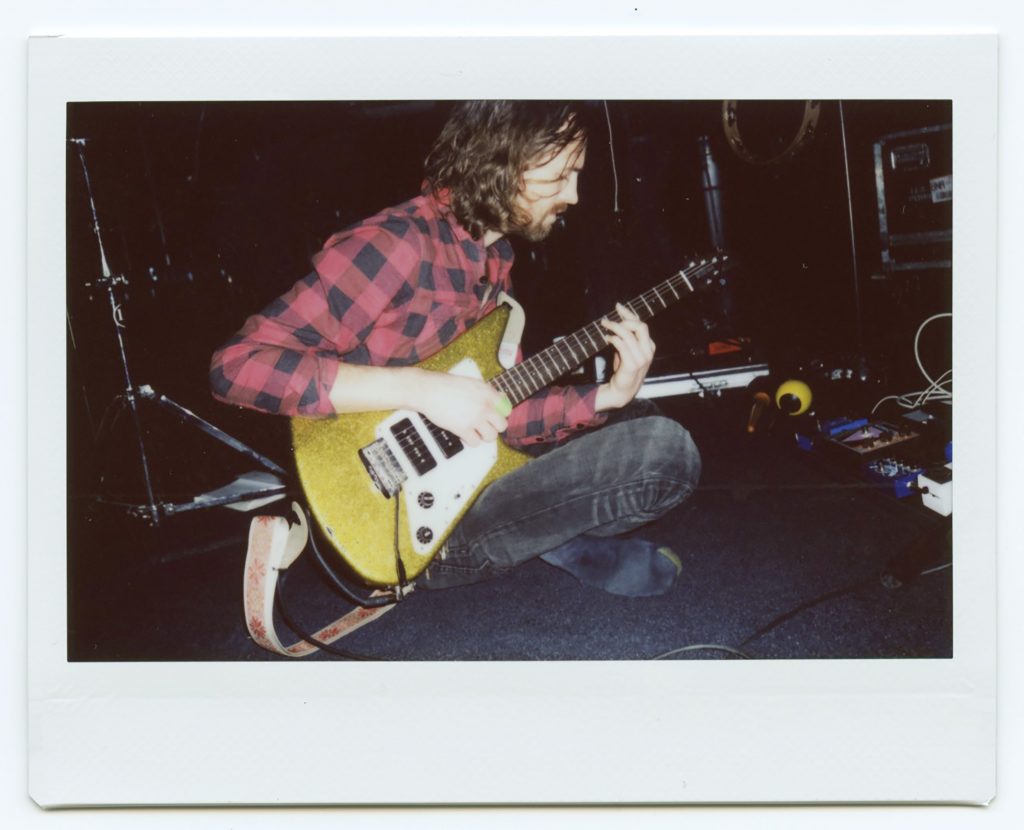

While the show’s undoubtedly rowdy, it’s not the straight-up hazardous affair that I saw at Bonnaroo in ’09. Instead of a spandex suit, Matt’s wearing a red-striped jacket that makes him look like a ringleader who’s into Saint Laurent. There are no kids bumrushing the stage, and I’m not worried about breaking any bones. The chaos of early Cage shows has seemingly been replaced by tighter instrumentation, stronger vocals, and a new reserved intensity, and I’m left to wonder: Is this what a matured, cautious Cage the Elephant looks like?

Then, as the band launches into “In One Ear,” Matt points to a spot in the crowd like Babe Ruth calling his shot in Wrigley. After a couple of seconds of deliberation, he’s walking on top of a sea of kids a la Iggy Pop—just like when I saw them in ’09. Well, maybe not too cautious.