Of all the improbable tasks, to be an artist has to be one of the best. But not far down the list would be the namer of clouds.

It’s a task that began with the first International Cloud Atlas, published in 1896 by the World Meteorological Association (WMO), which categorized clouds by genus, species, and variety. The names are the epitome of lay-scientist delight, with Latin-derived titles that carry their own poetry: cirrus refers to a tuft of hair or bird’s feathers; castellanus conjures the castle of a fortified town. The last time a new cloud type was added to the Atlas was in 1951: the cirrus intortus, or “an entangled lock of hair.” But in 2017, shortly after artist Marilyn Murphy joined the Cloud Appreciation Society, a new type of cloud made history.

The members of the Cloud Appreciation Society, founded in 2005 by Gavin Pretor-Pinney (a former absinthe importer), noticed what would eventually be called undulatus asperatus, or “turbulent undulation,” a low-lying cloud that looks like the underside of a roiling sea. Pretor-Pinney submitted the cloud to the WMO for consideration, and it was added to the Atlas in 2017. Citizen cloudspotters became, improbably, cloud namers.

Murphy’s love for clouds goes back to her earliest roots, to her childhood in Oklahoma at the foothills of the Ozarks. “My family was always kind of sky-oriented,” Murphy says, explaining that her mother could fly planes before she learned to drive. “That’s the only thing my mother ever got after me about. She never said, ‘You need to get married,’ or ‘You need to have kids.’ She’d always say, ‘Honey, I just know you’d be the best pilot in the family.’”

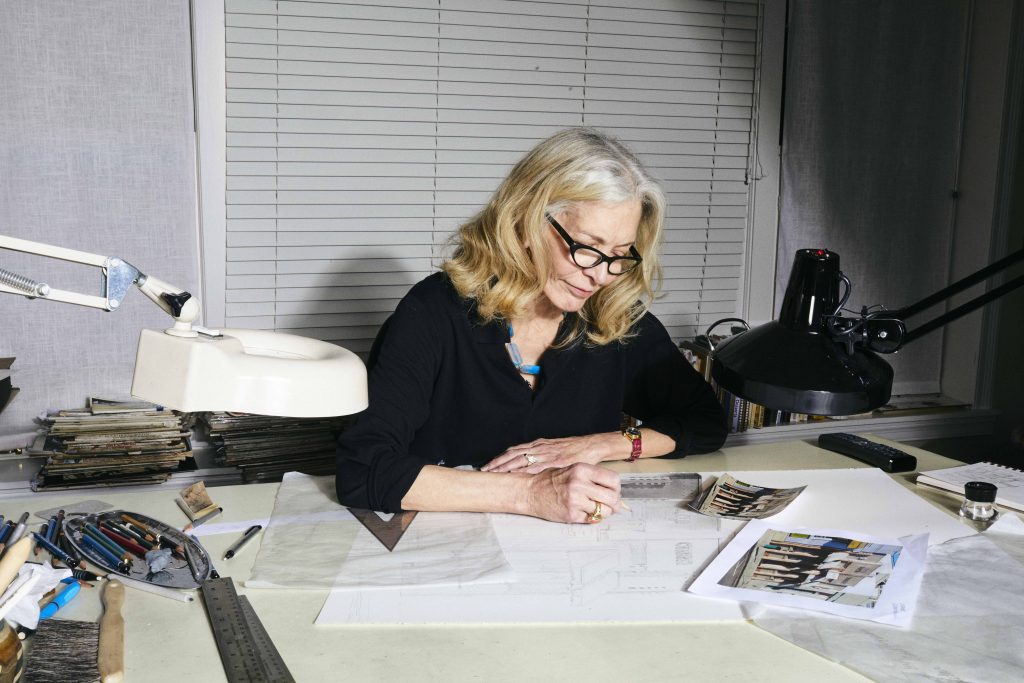

That Oklahoma sky, from its distinct, defined light and shadows to its threatening gusts of wind, has informed Murphy’s thirty-nine years of oil paintings and graphite drawings. Big fluffy clouds are the dominant thread through Murphy’s latest exhibition, Atmospheric Perspective. It’s her seventh solo show at Cumberland Gallery and the gallery’s penultimate show before its closing in the spring of 2019. In these pieces, cumulus clouds obscure the horizon and any sense of reality, and Murphy’s subjects, posed in their too-shiny American midcentury sensibility, often have their heads literally in the clouds.

“Atmospheric perspective is the way to create the illusion of depth on a two-dimensional surface,” Murphy explains of the show’s title. She is, after all, a Vanderbilt professor emerita of art. “Linear perspective is like railroad tracks going off into the distance. Atmospheric perspective, you can see easily coming down, say, Hillsboro Road toward Green Hills from town. You can see the mountains are softer, the colors get cooler in the distance. The contrast becomes softer and a little more pale, less highlights, less deep shadows.”

On the afternoon of our conversation, fog has crept in outside Murphy’s Green Hills home, and the hills are hidden. The sky has fallen down on top of us. Inside Murphy’s house—unassuming from the outside, a museum on the inside, or perhaps an asylum for conscientious collectors—every inch deserves a close look. (“We’re maximalists,” Murphy says of herself and her husband, Wayne Roland Brown.)

The “fire room” displays Murphy’s fire paintings against black walls. On the mantle of the intricate marble fireplace are six brass airplane ashtrays (on one balances a cigarette—no, wait, that’s a pen that just looks like a cigarette) and a lava lamp. There are model trains, an animatronic dog made of twinkle lights, and golden logs in the fire. I recently heard about a man who was given visual exercises to repair his sight after peering through a single-lens microscope for many years. Some time spent in Murphy’s home would’ve been a nice prescription.

In the kitchen, Murphy makes a half-decaf cup of coffee and pours me a tipple of really good gin: “Oh, be joyful, my mother used to say.” Indeed, if there were any words to sum up Murphy’s work, it would be those—or maybe Murphy’s favorite exclamation, “Hot dog!”

To be the namer of clouds seems fantastical, but no more so than the tasks being carried out by Murphy’s figures, who have previously battled oversize desserts, rolled bocce balls into roaring cane fires, and flown creamers as if they were kites. In Atmospheric Perspective, women in reinforced hose plump pillows, men dive face-first into cushions, and one young woman lounges in the sky. The latter is titled Cloud Nine, referencing an idiom that, Murphy explains, refers to the ninth cloud listed in the Cloud Atlas, the towering thunderhead cumulonimbus—a sight as beautiful as it can be portentous. “Isn’t that great?” she says. “People are still saying that. They know it means you’re happy. You’re up there.”

It is with tangible glee that Murphy dances between the postwar gloss of midcentury imagery and her own brand of small-town, domestic surrealism. Like a smile pulled a bit too tight, there’s a frisson of disquiet in scenes where people seem a bit too calm to be going about their tasks. In the hands of a lesser artist, the banality of these classic American tropes would likely feel trite, maybe a little wistful, but as critic Peter Frank once wrote of Murphy’s work, “Normal has sprung a leak.” Apparently, we’re not in Kansas anymore.

“I want a visually seductive image, but on the other hand, I want a little discomfort,” Murphy says. “Is that guy going to fall to his death, or is he flying? . . . The surrealist manifesto was [about] tapping into your dreams for those improbable connections that you don’t find in real life. When I first started [making art], I would have a lot of improbable dreams going on. A brick curtain, a couch with arms. One of my professors said, ‘This would be a lot more powerful if you only had one of those things going on at a time.’ And I thought, Oh, well I’ll try it and we’ll see. And I tried it and it worked. I’ve become a true believer . . . in setting the stage, a completely believable stage, and then having a little twist or surprise or something curious.”

Within Atmospheric Perspective, the presence of floating (or falling) pillows reinforces the assumption that we’ve entered some dreamscape. Furthermore, the viewer is unlikely to see a full face, as most of Murphy’s figures have been cut off. With no expression or personality to focus on, the viewer is directed toward those improbable tasks—like in some dreams, where people seem to flicker in and out.

What little we do see of those faces is nearly always pleasant, capturing that polish of perfectionism and glamour of Murphy’s parents’ heyday. The 1940s and ’50s were a time of optimism, both real and manufactured, and with an eye to these decades, Murphy collects piles of magazines—Life, Popular Science, and Popular Mechanics—where she has discovered wonderful “visions of the future” such as flying vehicles (the clownish flying contraption in the painting Modern Mechanix comes from some 1935 concept art) and a rather industrious pre–Martha Stewart attitude.

“It’s like: Don’t throw away that chair, you can cut off the top of it and turn it into a side table. Or take that barrel and turn it into a chair!” Murphy says, delighted. “Here are some simple plans for making a plastic lamp! It’s all things you can do . . . Maybe coming out of World War II, the country thought, Wow! I didn’t know we could do that! I didn’t know we could make a difference. Now, let’s build highways.”

But before we get too romantic about the way things were, Murphy’s surrealism spirits us away. The term nostalgic has been used in reference to her work, but that doesn’t seem quite right. Her twists keep these scenes from being too rosy.

“That’s one of the things that always drew me to surrealism,” Murphy says. “Mom showed me a little gray picture of Salvador Dali’s limp watches, The Persistence of Memory . . . As a little kid, I looked at that and went, what? I just thought, How can someone have that kind of imagination? I want to think like that too! You know, a limp watch is ruined. It should be ruined, really. But how fabulous.”

Perhaps one of the elements that puts me most at unease with Murphy’s work is the pervasiveness of the pretty girls, who sometimes seem to play into the madness of their strange tasks, with odd, plastered smiles. Other times they’re apparently naive, caught in a world that’s fallen into the absurd. Murphy agrees with this, in a way that suggests she’s more interested in my reaction than anything else.

“[In a show in St. Louis,] I had this painting of a woman,” Murphy says. “She looked like she was in a nutritionist’s outfit. She had the stove open, and there was a little house in the oven . . . I was giving a little gallery tour, and I said, ‘This is Home Cooking.’ Wayne and I had been looking for a house forever. We had been looking for a year, a couple of years or something. I had wanted a Craftsman bungalow then. So I told that story, my story, and this woman in the group said,”—Murphy drops her voice to a low, threatening groan—“‘That is not what it’s about. That woman is sick of cleaning up after her family, vacuuming the floors, doing the dishes, cooking, doing the wash. She’s ready to take that house, and she’s going to put it in that oven and burn it up!’” Murphy flashes a surprised smile. “And I went, ‘You’re right! You’re absolutely right!’ It really stunned me, but it was her story, and that’s as valid as my story.”

Clearly, there’s more than one way to plump a pillow. Within Murphy’s world, the shadows and light might be crisp, but the rules are barely defined. Hot dog!

Atmospheric Perspective is showing now through December 22 at Cumberland Gallery.

Suggested Content

Chelsea Kaiah James

Why aren't there any ears sculpted onto the presidents of Mt. Rushmore? Because American doesn't know how to listen. - Unkown

Contributor Spotlight: Dylan Reyes

When I create, I often think of what Johannes Itten said, “He who wishes to become a master of color must see, feel, and experience each individual color in its endless combinations with all other colors.”. I’m also inspired frequently by love and loneliness and want folks consuming my work to be encouraged to start paying attention to the little details in everyday life, appreciate the simple things, and let them eventually inspire you! Ultimately, I’m just trying to become a mother fuckin master of color.

Secondhand Sorcery

A look inside the beautifully cheesy world of Crappy Magic