IN LATE 2014, twenty-two-year-old SueAnn Shiah strapped a GoPro and a couple saddlebags to her bike and dragged one aching friend on a 470-mile, 13-day journey around the entire coastline of Taiwan. Somewhere between the jungle and the sea, on the traditional bike trip known as huandao (literally, “around the island”) that has become a cherished rite of passage within Taiwanese culture, Shiah hoped to shake loose some answers about her dual identities, as an American and as the daughter of two Taiwanese parents. She shares her story in HuanDao, an 86-minute documentary and identity-by-biking odyssey that premiered in 2016 at Vanderbilt’s Scarritt Bennett Center.

Shiah, a 2014 Belmont graduate who is currently working as a music producer in Nashville, was raised speaking Taiwanese Mandarin in her home and attended a Chinese school just outside of Detroit, “where the suburbs meet the cornfields.”

But upon moving to the South to attend Belmont, Shiah felt a unique pain set in: the isolation and confusion of a non-white person discovering what it means to live somewhere so lacking in diversity. “I think a lot of us who make art are asking ourselves, How do I make something beautiful out of my pain?” Shiah says with a little laugh. “How do I find redemption in all my suffering, whatever it might be? I think that’s how I process, that’s how I deal with darkness and brokenness.”

Shiah and I are speaking at Ugly Mugs on the day before Christmas Eve. A section of her hair is shaved on the side, and in her bag is a T-shirt from giving blood earlier in the day, which she has done regularly since the shooting at Pulse.

Shiah goes on: “Often if we have enough comforts and privileges we can . . . segment ourselves away from having to engage that kind of stuff—self-medicate, whatever it is. But the answer’s not away, it’s through. What made me different from everybody else was the source of my pain, but the answer wasn’t to become like everyone else so I could avoid that. It was to embrace the thing. That’s how I could find my healing.”

Embrace seems like the perfect word for huandao, as the trip draws a loop around the island that looks a lot like a loving embrace. Or for Shiah, perhaps a surrounding shield for the place that she hoped would provide her with answers.

But as much as HuanDao was an attempt to find healing, that goal probably could’ve been accomplished simply by doing the bike tour. By turning it into a movie, she didn’t just go “through” her pain; she offered a glimpse of her journey for anyone who wants to see it. It was a way to help her connect, to counteract the alienation, and maybe, just maybe, help some other isolated Taiwanese-American kid.

Shiah’s search for Taiwanese identity is a much more complicated question than simply discovering roots, tying together past and present—all those normal coming-of-age things. To this day, Taiwan is denied statehood by Mainland China. “Taiwanese identity is inherently political, because of the really nefarious diplomatic situation that is Taiwan,” Shiah explains. “To say that you’re Taiwanese as opposed to identifying as Chinese is an inherently political act.”

Shiah’s mother was born in Taiwan, and her father was born in Burma. After Japan’s defeat in World War II, the formerly occupied China saw a rise in communist power, which drove people like Shiah’s grandparents’ families to flee. In the film, Shiah’s mother shares the story of her family, who fled south to Taiwan, eventually landing in a military village in Luodong. Shiah’s father had a passport that read, “No country. No land.” After the Chinese Civil War, Taiwan was giving citizenship to displaced Chinese nationals, and so he landed there.

Therein lies the complication: Are her parents Chinese, or are they Taiwanese? What is Taiwanese identity, and how is it different from Chinese identity? “The language that we speak and the cultural practices that we have, and even traditional and religious and indigenous engagement, mirror that of Chinese culture,” says Shiah. “It’s fruitless and also shortsighted to have a conversation about what Taiwanese-American identity is without also talking about what Chinese- American identity is.”

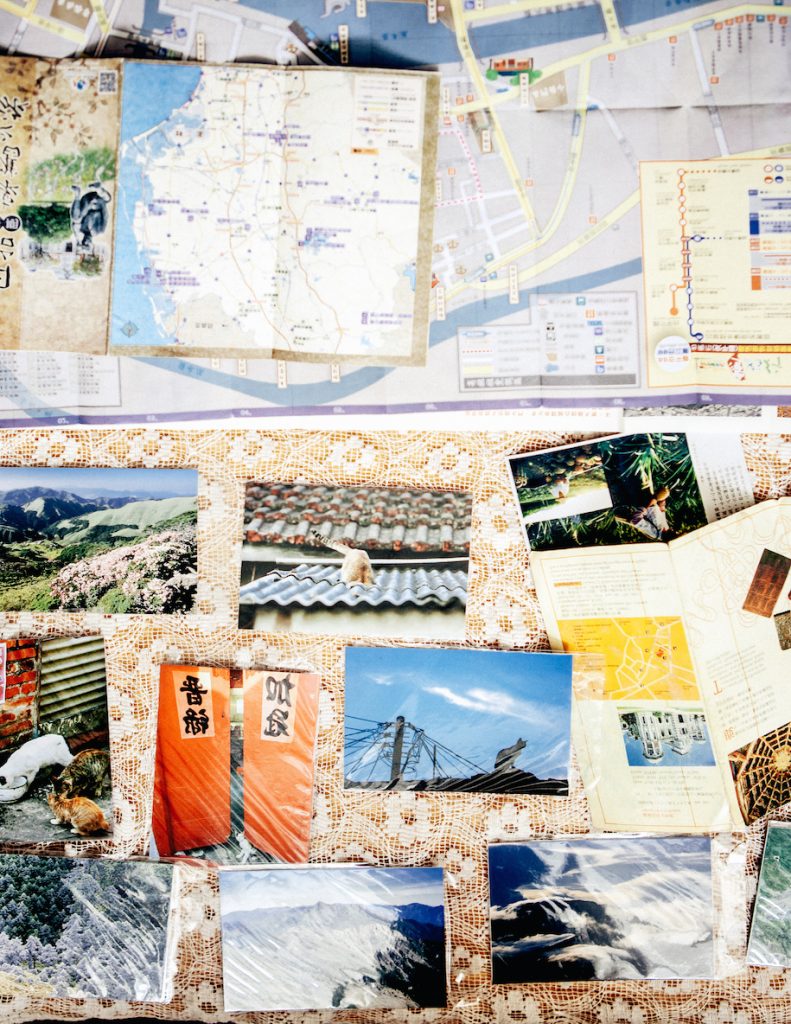

So on October 30, 2014, Shiah, along with director of photography Anne Zhou and Shiah’s white friend Rachel Akers (also twenty-two and from Michigan), began to bike the entire border of Taiwan. The trip, funded via Kickstarter, was captured through long shots as pavement, jungle, seacoast, and river gorges zip past. Interspersed are in-depth interviews with locals met throughout the countryside. Shiah and Akers, often wearing Halcyon Bike Shop shirts, stay in hostels and take occasional breaks to look out over the rocky edge of the sea, to pluck fruit from trees and hope they don’t get sick, and to discover caves, temples, and the stories of people they may never see again.

Shiah acts as a guide for the viewer, providing voice-over narration and sharing diary-like private moments with the camera to keep us in the loop about her emotional journey as well as the physical one. In these moments, Shiah is soft-spoken, sometimes almost stern or somber, as though she might be nervous about playing too much to the camera. The only times she shows animation similar to the person who sits across from me today is when sharing food with Akers or talking to locals—like when a group of aboriginal villagers invites the young women to visit and eat with them.

Just a few days into the girls’ tour, a group of aboriginal Taiwanese is hanging out around a red table covered with drinks and food. They invite the girls to sit down and chat and shoot footage of clams. A man shows off his handmade knife and later a spear the length of his body. Speaking in Mandarin, Shiah finds common ground with this group of women and men through their dual cultures: they are in a similar situation as she is, as they have their own culture separate from their majority countrymen and women. Of the Taiwanese population of 23.5 million, 98 percent are Han Chinese and only 2 percent are aboriginal. “We must preserve our own traditions,” says a man in a gray T-shirt and buzzed silver hair, “so that we can continue to pass them on, it’s like this.”

Shiah responds: “A person and their native land have a bond. But I think it’s hard, like I grew up in America and sometimes feel like America isn’t my home. When I’m in Taiwan, I feel like me, Taiwan, and the Taiwanese people have a bond. But when I’m in Taiwan, I will miss America too.”

Introspective, immersive moments like this are the heart of the film. Language provides an obvious gateway for Shiah, as she was able to “meet some random musicians” and record aboriginal music for the film’s soundtrack. An interview with two charismatic, chatty hostel owners reveals a village’s attempts to stay relevant and hook tourists while preserving their history. A tea service in a town above the cloudline is incredibly fascinating and nearly meditative.

“It’s preparation,” Shiah says of the serendipitous nature of these encounters. “People in Nashville talk about the practice of songwriting, and it’s not like you walk around one day and then you write an amazing song. You prepare and you hone your craft . . . so that when inspiration does hit, you are equipped to ride the wave, so to speak. You can’t manufacture when the wave is going to come, but you have to be ready for when it does, so you can ride it!” Shiah laughs. “The only rule I have for people is that people will always surprise you. You need to leave room for creativity to strike or happenstance or people you meet along the road.”

During the conversation with the aboriginal villagers, Akers, who speaks no Mandarin (her second language is German), sits quietly. She’s noticeably separate, her hands clasped between her knees, and throughout the film, she never shares her own experience of being an outsider in these moments. But the viewer notices.

“In order to see detail, you’ve got to turn the contrast up,” Shiah says. Akers was intended to provide contrast, but perhaps what she did better was provide a mirror opposite to Shiah’s parents, who also came on the trip. They didn’t bike with the girls, but from time to time, they joined for meals. On this trip of identity, Shiah brought specters of her two conflicting identities in tow, through the people that traveled with her: her Taiwanese family and her white friend.

Shiah’s parents came to the United States from Taiwan about thirty years ago, and she had traveled with her family to Taiwan several times before the huandao. Her extended family lives in the capital city, Taipei, and she also studied abroad in Taipei between her sophomore and junior years of college. But in discovering the rural areas of Taiwan, Shiah began to reevaluate everything she thought she knew about the island.

“I realized I had a very limited understanding . . . because my experience was limited to Taipei,” Shiah says. “My understanding of what Taiwan is to me is different than someone whose family has been in Taiwan for hundreds of years, which is different from someone who is aboriginal, who has been there for thousands of years. For that, you have to go to different places. You have to meet people from different areas.”

For people caught between cultures—or even caught between lands—stories like HuanDao could provide some salience for the search for redemption. For Shiah, the act of telling her story provided just that and more.

The print version of this article incorrectly stated that HuanDao premiered at the Sarratt Student Center. It also incorrectly stated that Shiah’s father was born in Taiwan. Our apologies for the errors.