Frank Varallo Sr’s biography reads like a mad lib. He was an accomplished violinist who played at Teddy Roosevelt’s inauguration. He was an avid hunter who frequently traveled to South America. He spoke seven different languages and was a translator at Ellis Island. But his claim to fame—at least here in Tennessee—is that he opened a chili parlor that eventually became the oldest restaurant in state history, one that is still open to this day.

“They say he got in a hunting accident and couldn’t play the violin anymore, so he opened a restaurant,” says Todd Varallo, Frank Sr’s great grandson and current owner of Varallo’s Chili Parlor & Restaurant.

Todd and I are sitting across a red and white checkered table at his restaurant, which is located on 4th Avenue North, at the entrance of The Arcade. The restaurant used to be called Varallo’s Too when it opened in 1994. The flagship Varallo’s, which was on Church Street, opened in 1907 and closed in 1998. Frank Varallo Jr., Todd’s grandfather, worked there until he was eighty-six years old.

Todd has worked at The Arcade since this location opened (and on Church Street before that), but more than thirty years later he’s showing no signs of slowing down. He says he gets in around 3 a.m. each morning and normally puts in a twelve-hour day.

I meet Todd on a Thursday, which happens to be food truck day on Deaderick Street. This usually means the lunch rush isn’t as unremitting as the rest of the week. However, Todd is understaffed on this particular Thursday, so he’s busy taking orders, answering phones, and working the register. When he gets a free moment, he darts over to sit with me and patiently answer my questions. But I’m at the mercy of the crowd, which even on a “slow” day is relentless. Each time the phone rings or diners walk in the door, Todd dutifully springs up and finishes his answer from across the restaurant. When he returns to my table he delivers a friendly but terse, “What else?”

Most of our segmented interview concerns the restaurants’ histories. Todd tells me the Church Street parlor was a popular rendezvous for some of the most powerful people in Nashville—politicians, journalists, even judges. In an email, Rep. Jim Cooper tells me he tries to stop by Varallo’s whenever he can. He calls it a “Nashville institution.”

“The old restaurant, we had different dining rooms,” Todd says. “So my grandfather closed off one of the back dining rooms where all the judges sat, so they got to be in their own little room.”

When I go for lunch, there are no politicians that I recognize, but the crowd is noticeably eclectic. There are men in suits donning long wool coats, women in hard hats paying in change, and a group of young people at a center table discussing if they could make it in California. It’s not hard to see why these otherwise dissimilar groups find themselves together at Varallo’s, hunched over steaming styrofoam bowls of chili. For one, the location is central to a lot of Nashville’s largest office buildings, so it lends itself to a quick lunch break for people working in the city. And in a downtown that’s sprouting bro-country honky-tonks faster than you can say “Bawitdaba,” many people are searching for a meal that is authentically Nashville. There’s nothing more authentic than Varallo’s.

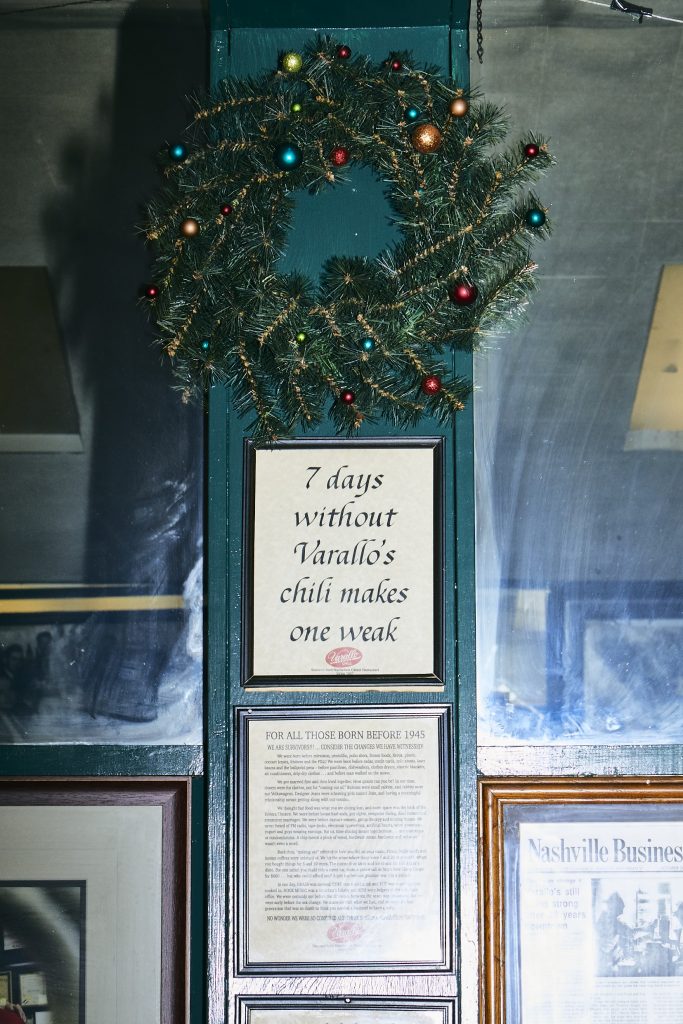

In fact, some may criticize the restaurant for being a little too authentic, insofar as it’s hardly changed since 1994. There are no iPad registers, trendy bar stools, or exposed Edison bulbs. All the cutlery is plastic, and all the bowls are styrofoam. Many of the decorations in the restaurant are older than the restaurant itself. Massive black-and-white photographs of Varallo men are hanging from the walls, bordered by decades of yellowed newspaper clippings recognizing the restaurant for its food, longevity, or both. A poster from Hatch Show Print hangs near the register, commemorating Varallo’s for one hundred years of business, as does a congressional record from Representative Cooper. Behind the register is a photograph of the rolling hills of Viggiano, where the Varallo family emigrated from.

“Some people like history and some people don’t. I have some of the young ones come in and they’re like, ‘Oh man this is cool, we got to keep you going,’” Todd says. “And of course you got the other ones. We have some people walk in and we’re not fancy enough. They turn around and leave.”

A quick look over the Varallo’s menu isn’t going to blow anyone away, especially the foodies in Nashville searching for the next innovative kitchen. The menu has changed so little over the years that it might as well be carved into stone, but can you blame them? (I mean, they have been open for more than a century.) Plus, the food is really freaking delicious. When I go for lunch, I opt for the chili (duh). The legendary Cheryl McKnight, who has worked at Varallo’s for forty-two years, serves me their famous “three-way” chili: beans, spaghetti, and a tamale, the perfect meal for a chilly December afternoon. I pass on a recommended side of grilled cheese, though it appears the regulars don’t have it any other way.

The chili (they spell it “chile” on the menu, no one is certain as to why) is what made the Varallo’s name famous, and it’s the same recipe that Frank Sr. used when he opened the Church Street restaurant. He credited the recipe to the family he lived with during his South American hunting excursions. The rest of the menu is pretty much standard fare—burgers, fried chicken, some vegetables. They also serve breakfast daily. What does jump out about the menu, though, are the remarkably low prices. My chili was less than five dollars. This is intentional.

“Well I mean we’re more toward working people, not tourists,” Todd says. “If people work for the state, they can’t afford fifteen-dollar cheeseburgers, so we’ve always been more toward working people.”

For a restaurant with such a glorious past, the future is very uncertain for Varallo’s. Todd has three daughters who are decidedly against taking over the restaurant once he retires. His son-in-law showed a little interest but ultimately passed. Todd doesn’t blame them; even he didn’t want to work at the restaurant as a young man. But after college he was married with a baby on the way, and suddenly the restaurant business didn’t look too bad. “It was kind of fate,” he says.

Fate, however, hasn’t been kind to some of Todd’s neighbors. With The Urban Juicer sandwiched between a cobbler and The Peanut Shop (opened in 1927), it’s evident that the slow crawl of gentrification is making its way through The Arcade. Flocks of Bird scooters are parked outside the entrance like Silicon Valley gargoyles. Luckily for Todd Varallo, his restaurant remains a bulwark against a twenty-first-century dining experience.

“I don’t own a computer. Everybody thinks I’m crazy,” Todd says. “All my paperwork is done old school. I still write checks for everything I pay.”

At a certain point, the resistance to change is to be expected from Varallo’s (have I mentioned they’ve been open for a hundred years?). As Todd likes to say, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

If only they could fix the rest of the city. As more and more restaurants flood downtown Nashville, Todd finds it more difficult to find steady help.

“You have so many people just floating around to whoever can give them the most money,” he explains. This was never a problem for the Varallo men before Todd. Multiple people worked at the Church Street parlor for over fifty years each, Todd tells me. They just don’t make them like Cheryl anymore.

I ask Todd if he’s thought about expanding in any way, maybe putting the parlor on wheels and joining the caravan on Deaderick Street. He hates that idea.

“I just do what I do. I don’t really worry about anyone else,” Todd says. “I’m just thankful for everybody that walks in the door.”

Varallo’s is open Monday through Friday from 6:00 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. They have a website—if you can believe it—at varallosnashville.com.

Suggested Content

Can You Dig It?

How urban farming nonprofit Trap Garden is working to eradicate Nashville’s food deserts

Double Scoop of Happiness

Kokos Ice Cream creators Jerusa van Lith and Sam Brooker want to show you just how good ice cream can be.